Last summer over 130 fires roared across Manitoba, causing as many as 1,000 people living in Pimachiowin Aki to evacuate to Winnipeg. While fires can negatively impact people living in the area, some wildlife species thrive.

Forest fires are an inevitable part of the boreal forest life cycle. They are as crucial to forests as sun and rain.

As the upper canopy of trees burns, the forest floor receives more sunlight and water, allowing different species of trees, plants, insects, and wildlife to settle in.

While some species adapt to changing landscapes, others struggle. We look at four species in Pimachiowin Aki and their responses to increased fire frequency and intensity:

1. Wolverine

Wolverines are an elusive species and largest member of the weasel family. They travel long distances (especially males) and live in small packs far from civilization. They’re carnivores and scavengers, relying on other animals for food. They are ferocious predators and prey mostly on small mammals like rabbits. They also eat carcasses of large animals like boreal woodland caribou when other food is scarce.

“They eat whatever they can find,” says Guardian Dennis Keeper, Little Grand Rapids First Nation. “They eat snowshoe hare, so they’re found where the highest population of rabbits are.”

What happens to wolverines after a forest fire?

When a fire rips through a forest, it burns food sources for many species, including boreal woodland caribou. Without lichen, caribou move on in search of this favoured food source. Wolves follow closely behind, leaving wolverines to hunt for themselves.

Despite their ability to travel long distances and lack of dependence on a particular habitat, wolverines struggle when their livable territory burns. Forest fires force wolverines closer together, increasing competition for food and territory. These tough animals are incredibly territorial and turn on each other. They fight over territory, food, and females.

In Ontario disturbances could pit the few hundred wolverines against one another. They really beat each other up.

Wildfire researcher Matt Scrafford discusses negative effects of wildfire on wolverines in a 2021 CBC interview

2. Snowshoe Hare

When wildfire burns through the boreal forest, it allows plants on the forest floor to reach sunlight and grow, providing ample opportunities for hares to hide and raise their young in shrubs and undergrowth. Their numbers are known to exponentially rise in a younger forest. In fact, snowshoe hares fare better when living away from mature forests. As maturing jack pine leaves become harder to reach, hare populations decline.

Hares eat smoked leaves in nogoomekay akisakeytek (newly burned areas).

Guardian Dennis Keeper stayed in Little Grand Rapids First Nation to monitor last year’s wildfires. He has been documenting hare populations in Little Grand Rapids First Nation and reports that hare populations are abundant.

Hares usually spend daylight hours sheltered under bush, stumps, or logs and become more active after sundown. Even when sleeping or grooming, they remain alert for predators like marten, lynx and fisher, which travel from old growth denning sites to burned areas to hunt hares.

“Many wildlife species eat hare,” Dennis says. The wildfire that burned through Little Grand Rapids in 2018 has already regrown with shrubs, ideal for snowshoe hare to live and raise their young. Predators will follow. “There’s always predators right behind them, like lynx.”

3. Lynx

Canadian lynx prefer habitats with old-growth trees and little to no brush on the forest floor. However, they live in places with new growth—like a fresh forest after a fire—if it has abundant food.

“You won’t see lynx because they are shy and elusive,” says Guardian Dennis Keeper, who grew up in Pimachiowin Aki and is an avid hunter and trapper. Though Dennis has seen “only a few” lynx in his life, he knows they’re around. “I see their tracks,” he says. Plus—where there’s hare, there’s lynx.

Abundant hares attract lynx to regenerating forests—snowshoe hare is the lynx’s main source of food. The more hares in an area, the more lynx that arrive to eat them. This is called the hare-lynx cycle.

The hare-lynx cycle is part of forest regrowth, but it doesn’t last forever. The more hares lynx eat, the fewer hares left to feed on. Plus, as new forest grows taller, twigs, buds and needles are out of hares’ reach. Now, both lynx and hares have less food. As hare populations dwindle, lynx populations also decline.

The hare-lynx cycle lasts 8-11 years.

4. Black Fire Beetle

Wildfires don’t destroy everything. In fact, they are source of life for black fire beetles, which fly to forest fires in great numbers and mate while fires still burn.

The black fire can detect heat from forest fires burning between 50 and perhaps as far as 130 miles away.

academic.oup.com

Jordan Bannerman, Instructor II, Department of Entomology, University of Manitoba explains, black fire beetles have infrared sensors on their thorax that allow them to detect heat emanating from fires (Reference). “Heat produced from even a small fire is sufficient to attract them,” he adds. “They can also detect certain chemicals emitted from burning wood that are present in smoke.”

Females deposit eggs under the bark of dead and dying coniferous trees, leaving larvae to safely develop and hatch with few predators around. “Egg laying has sometimes been observed in trees that are still smouldering,” says Jordan.

He says that “a dying tree will also have weaker defences and be more or less free from competitors, which provides the black fire beetle with a big advantage.”

Most predators leave burned areas, but black-backed woodpeckers stick around to feast on the black fire beetle’s wood-eating larvae and other wood-boring insects, which thrive on burned boreal trees.

Do black fire beetles help or harm boreal forests ?

Jordan says, “these beetles are beneficial in that they are important primary decomposers that play a role in forest regeneration.” Black fire beetles start the decomposition process early, setting the stage for other insects to further break down the dead matter and release nutrients into the soil.

Did you know that blueberries come after fire and feed a lot of animals?

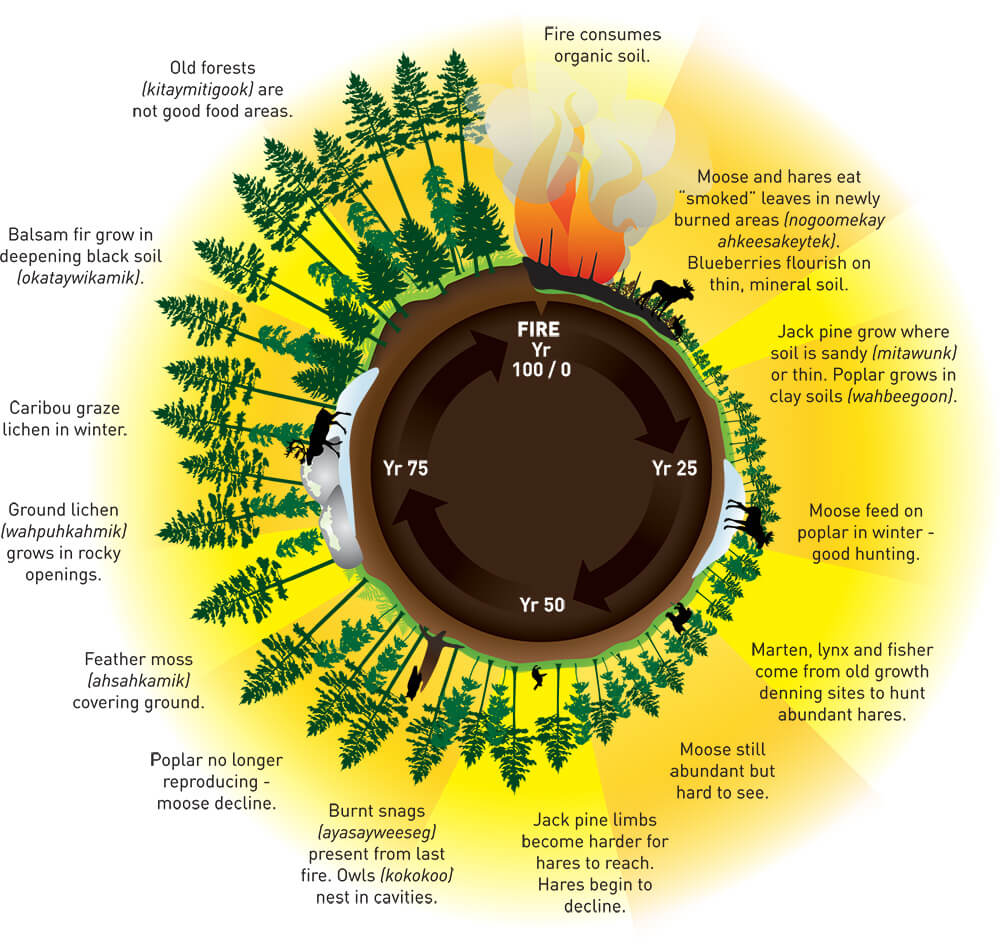

Wildfire sets a lot in motion in the boreal forest. Take a look at this 100 year-cycle:

Pimachiowin Aki is the largest protected area in the boreal shield ecosystems of North America. It is 2,904,000 hectares of natural habitat for plants to thrive and wildlife to eat, shelter, and raise their young.