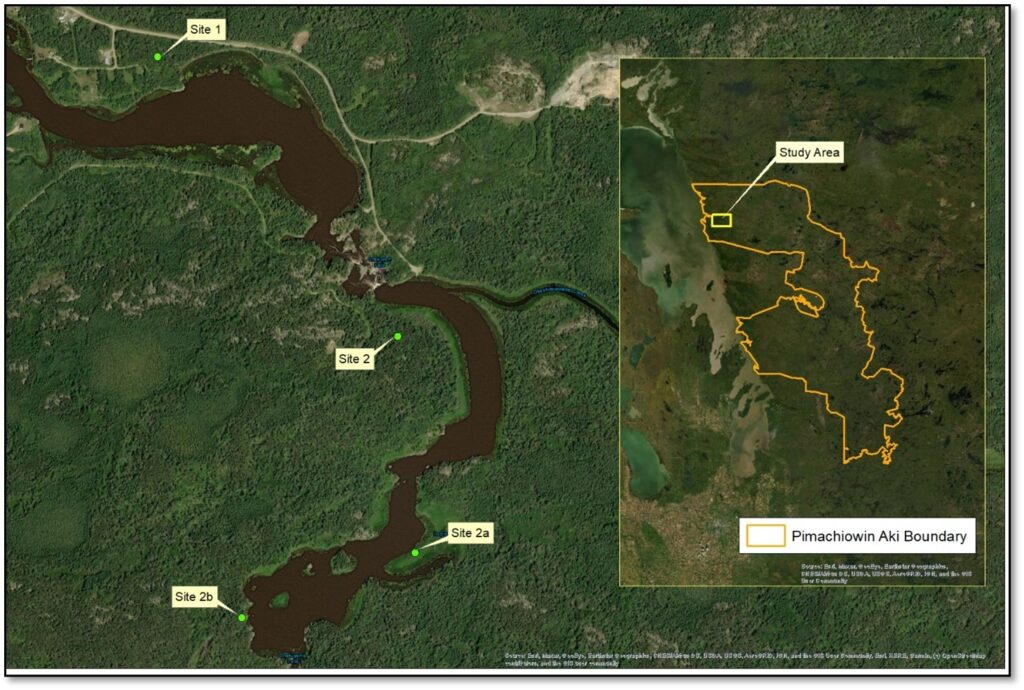

Irene Fogarty’s PhD research began with a question: how can Indigenous-led conservation guide the future? She found answers in the story of Pimachiowin Aki.

1. Congratulations on completing your doctorate! We first met you in March 2020 when you approached Pimachiowin Aki to participate in your PhD research. Your research focuses on Indigenous Peoples and the guardianship of protected areas in Canada including current and tentative World Heritage sites. Can you explain more about this?

Thank you! The greatest honour I had during my doctorate was the opportunity to meet some of my heroes: the Board and Anishinaabe community members of Pimachiowin Aki. The aim of the study was to show how important it is to empower Indigenous Peoples in protecting traditional lands and waters, including through formal partnerships with provincial and federal governments. Pimachiowin Aki is a great example for how to do this.

2. What drew you to this research— was there a moment or story that sparked your interest?

Really, it was the injustice of how Indigenous Peoples are treated in Canada, including in protected areas conservation. While Canada has taken many positive steps to finance Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas, only some World Heritage sites in the state have Indigenous Peoples in formal, equal decision-making partnerships alongside federal or provincial authorities. The partnership between Bloodvein River, Pauingassi, Little Grand Rapids and Poplar River First Nations and the provincial governments sets a positive example of formal, shared decision-making in numbered Treaty territory. Anishinaabeg drove the World Heritage nomination. This, along with their determination and resilience to see the site protected, shows the power of Indigenous leadership to make positive changes that benefit everyone.

3. You interviewed 43 people across Canada and internationally, including 18 people from Pimachiowin Aki. Was there a conversation or moment during your interviews that stayed with you— something that changed how you see protected areas conservation?

I was honoured and humbled to have spoken with every person who contributed from Pimachiowin Aki. Everyone was so patient and generous with their time. I was moved by how the First Nation communities wanted to protect Pimachiowin Aki as a World Heritage site for the benefit of all. Ed Hudson and Ray Rabliauskas of Poplar River explained how Elders saw what’s happening in this world and wanted to make sure it would be saved for everybody’s benefit. Looking at how Indigenous Peoples are treated in Canada, this is a profound gift. William Young of Bloodvein and Clinton Keeper of Little Grand Rapids both spoke of the importance of ceremonies and their concern for loss of language and culture – a concern shared by many participants. Lands Guardian Melba Green and Councillor Ellen Young, both in Bloodvein, are amazing women. They spoke to me about the importance of encouraging Anishinaabe knowledge and culture in the classroom.

I was so grateful I got to meet Joe Owen of Pauingassi First Nation.

Joe Owen passed away in August 2023

I was so grateful I got to meet Joe Owen of Pauingassi First Nation. He’s a huge loss. He spoke of learning out on the land with family, as did three Bloodvein community members. It was wonderful to hear these recollections. Bruce Bremner and Gord Jones spoke about the difficulties of the World Heritage inscription and the challenges faced by the Pimachiowin Aki partners. Hearing this firsthand really brought home the challenges for everyone. Their insights showed how important it was that the communities kept fighting to get World Heritage recognition, because it compelled the World Heritage system to adopt better processes. Those are just a few examples off the top of my head, but everyone’s contribution was a privilege to hear, and so important. I also found it very moving how Anishinaabeg uphold the Seven Teachings, including through the determination to protect Pimachiowin Aki and all its beings, and have a willingness to work with everyone nationally and internationally to do so. Everyone should learn the Seven Teachings and take to heart the lessons provided by the communities of Pimachiowin Aki.

4. You describe Pimachiowin Aki as a case study in “how to do things right.” What makes this World Heritage site so unique and effective in your view?

The First Nations decided World Heritage inscription was the best way to protect the land and waters and all beings of Pimachiowin Aki. The idea of equitable partnership with the provinces to protect the site respects Treaty rights and constitutional rights of Indigenous Peoples. Furthermore, as the provincial and federal governments respected the aims of First Nations to have Pimachiowin Aki inscribed as a World Heritage site, this supported Article 31 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

The destruction of Indigenous Peoples’ relationships with lands and waters was a key strategy of settler colonialism.

Article 31 asserts that Indigenous Peoples have the right to protect, control and maintain their cultural heritage and knowledge systems. This right should be upheld by the state. Furthermore, the World Heritage inscription recognises the importance of protecting Anishinaabe culture as well as the Boreal territory. While the extent of international legal protection offered through the World Heritage Convention is somewhat limited, the inscription gives international visibility to the importance of protecting Anishinaabe culture and landscapes.

Another important point is how shared decision-making power through the Board is vital in challenging inequalities stemming from settler colonialism. The destruction of Indigenous Peoples’ relationships with lands and waters was a key strategy of settler colonialism. Anishinaabe leadership in decision-making for Pimachiowin Aki is vital in maintaining and restoring cultural and spiritual connections with the site.

5. Your research concludes that Pimachiowin Aki offers important lessons to the world. What are some of the lessons we should all pay attention to?

a) How have communities pushed back against coloniality in the World Heritage process—and what can other Indigenous Nations learn from that experience?

Coloniality refers to the unequal power relations which are rooted in colonialism and continue in the present to oppress and marginalise Indigenous Peoples. We see it in the treatment of Indigenous Peoples in healthcare; in broken Treaty promises; in the pollution of traditional territories by extractive industries; in the lack of progress with the Calls to Action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, etc.

The partners of Pimachiowin Aki did incredible work.

Coloniality is not just in Canada—those unequal power relations are everywhere. Another example of coloniality lies in the World Heritage processes which operated during the Pimachiowin Aki nomination. The partners of Pimachiowin Aki did incredible work in progressing with the nomination, yet some of the World Heritage evaluation processes were extremely unfair. They reflected a very “Eurocentric” view, i.e. a Western mindset which disrespected the worldviews of the First Nations. However, the Pimachiowin Aki partners persisted with the World Heritage bid, showing incredible resilience and determination. As a result, the World Heritage Committee made positive changes to ensure a more sensitive approach that better recognises the importance of supporting Indigenous Peoples.

It is important that researchers recognise they are not the expert. Rather they should listen and learn.

b) Respectful research—how did you approach your responsibility as a researcher working with communities who’ve often been studied but not listened to/ignored or misrepresented?

I was very aware that as an outsider I have very little knowledge about the lives and experiences of the Anishinaabe communities of Pimachiowin Aki. It is important that researchers recognise they are not the expert. Rather they should listen and learn. They should acknowledge the immense privilege of working with Indigenous communities. They need to act with humility and ensure Indigenous Peoples’ priorities are the real priority, not what the researcher may have in mind. Researchers should support of the goals of Indigenous communities. The Anishinaabe communities deserve recognition and absolute respect for all they have done at Pimachiowin Aki. To make sure I wasn’t misrepresenting anything, I sent copies of anything I wrote about Pimachiowin Aki to the Board for approval. I have also committed to making sure the stories and experiences of Pimachiowin Aki and its people are responsibly told and shared as widely as possible.

The planet is on its knees in terms of biodiversity loss and climate change.

c) Funding issues—What do they reveal about the federal government’s broader commitments to Indigenous-led conservation?

A huge issue for Pimachiowin Aki is the lack of sustained federal funding. While the provinces supported Pimachiowin Aki in the past, it is shocking that the federal government has not provided sufficient additional support. Among other things, this would help finance activities and initiatives to protect Anishinaabe culture which is directly linked to conservation of the Boreal landscape and all beings. Because of the World Heritage Convention, the state is obliged to provide finance for the continued protection of the site. However, this globally important World Heritage site is being ignored and to me, that’s a betrayal of the First Nations. A substantial investment by the federal government towards long-term conservation of the site is imperative. I note that the federal government, at the time of Pimachiowin Aki’s World Heritage inscription, was very happy to speak of this huge achievement. The government needs to move beyond empty gestures and words.

6. If there’s one message or insight from your research you want people to really take to heart, what would it be?

The planet is on its knees in terms of biodiversity loss and climate change. In many areas of Canada and internationally, Indigenous Peoples are doing the heavy lifting towards positive change. This is despite the continuity of appalling racism, marginalisation, oppression and environmental destruction affecting Indigenous Peoples. Indigenous leadership in protected areas conservation—and indeed land management as a whole—should be fully supported, fully respected and fully funded. This means:

- Centring Indigenous governance, laws and knowledges in all aspects of conservation

- Substantial funding towards Indigenous cultural continuity, intergenerational knowledge transmission and land-based learning

- Respecting the constitutional, Treaty and inherent rights of Indigenous Peoples in addition to internationally ascribed rights

Thank you, Irene. It has been wonderful to work with you. We appreciate what you have done to effect positive change for Indigenous-led stewardship and World Heritage.

Thank you.