Thank you to contributors Councillor Eddie Hudson, Poplar River Lands Guardians Norway Rabliauskas and Brad Bushie, Dr. Jeff Wells, and Elisha Corsiga (writer)

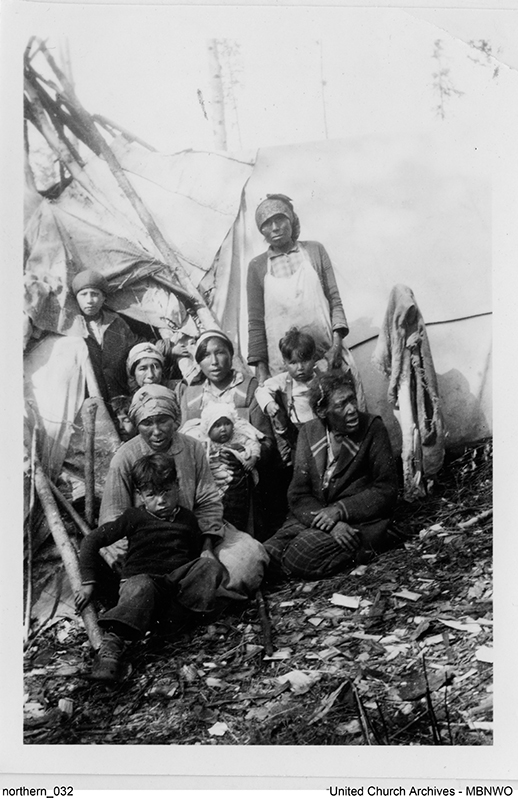

Our Elders and their ancestors have cared for our Traditional Lands for over 6,000 years.

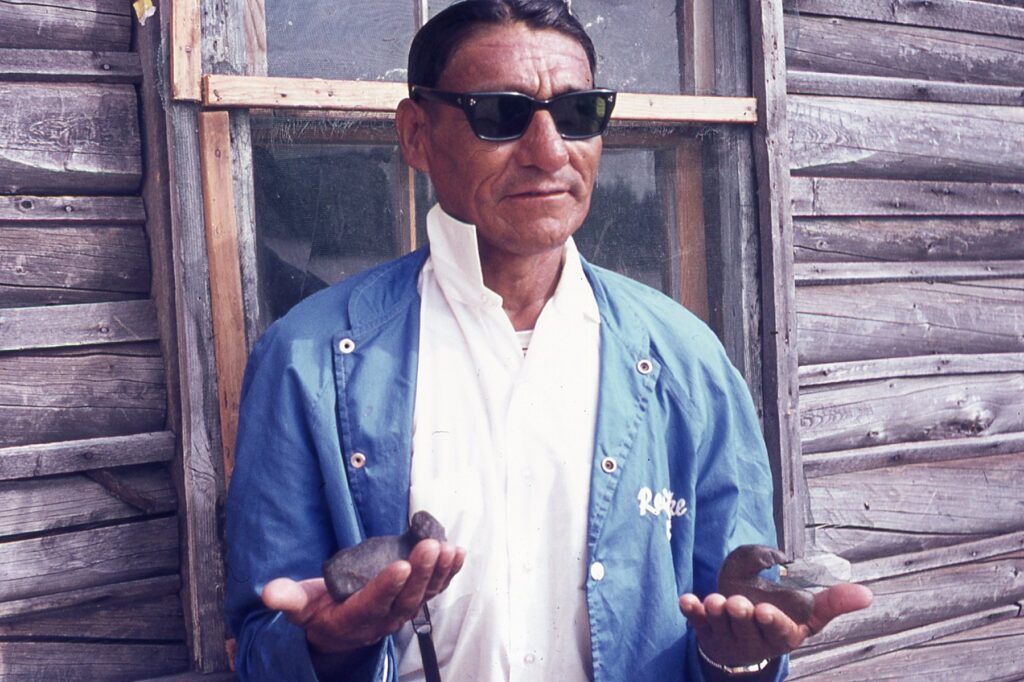

Protecting Pimachiowin Aki, which over 200 bird species rely on for survival, is an important example of how we care for the land,” says Poplar River First Nation Lands Councillor Eddie Hudson.

Since 2016, Poplar River Lands Guardian Norway Rabliauskas has been collaborating with scientists from Audubon’s Boreal Conservation program to better understand how songbird populations are changing in the face of climate change.

The first results of the ‘Songmeter Project’ are in.

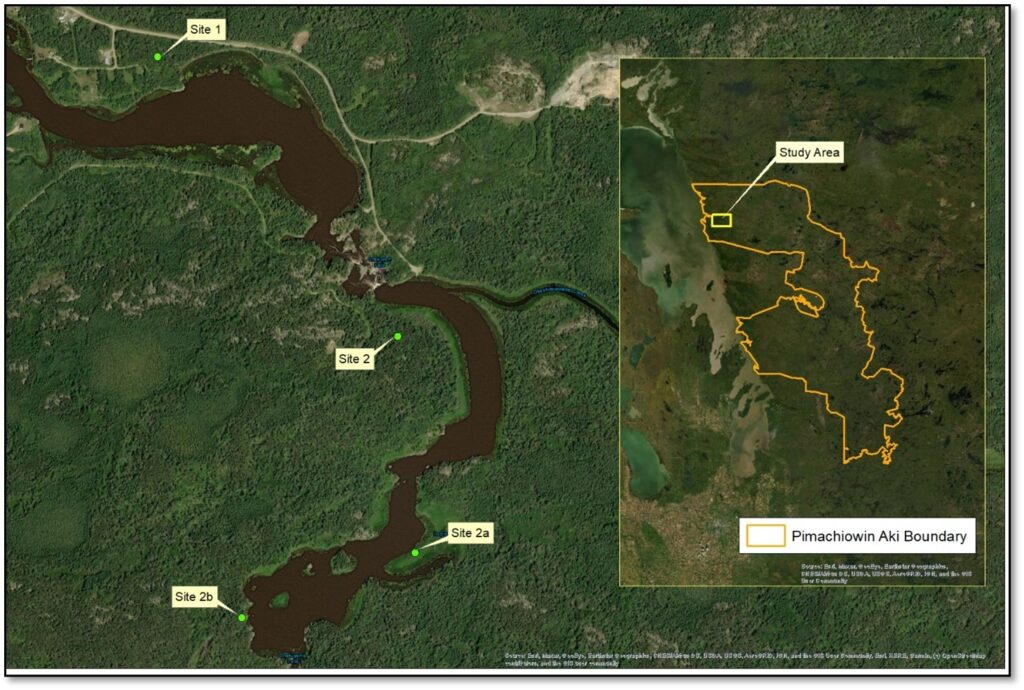

“Songmeters record bird sounds,” says Guardian Brad Bushie, Poplar River Lands Guardians Program. Using knowledge of the land, Poplar River Lands Guardians placed the recording units at four sites across the traditional territory, he explains.

The number of bird species recorded allows us to analyze population changes over time,” adds Dr. Jeff Wells, Vice President for Boreal Conservation at National Audubon Society.

- Guardians placed Songmeters in four survey sites in Poplar River First Nation throughout the spring of 2016

- 71 bird species were detected

- At least 18 of the species detected have more than 70% of their breeding range confined to the Boreal Forest biome, meaning their survival relies heavily on healthy landscapes like Pimachiowin Aki

- Two species were detected on more than half of all recordings:

- White-throated Sparrow

- Swainson’s Thrush

- Five species were detected on more than 30% of all recordings:

- Blackburnian Warbler

- Ovenbird

- Song Sparrow

- Bald Eagle

- American Crow

Photo: Hidehiro Otake

Photo: Lorne Coulson

- At least 20 species listed as special concern, threatened, or endangered by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) are believed to occur within Pimachiowin Aki. The Songmeter project captured recordings of three of the bird species listed by COSEWIC:

- Common Nighthawk

- Eastern Whip-poor-will

- Canada Warbler

Photo: Christian Artuso

Photo: Christian Artuso

Photo: Christian Artuso

- National Audubon Society’s recent study, Survival by Degrees, found that over two-thirds of North American birds are moderately or highly vulnerable to a global average temperature increase of 3°C by 2080. This includes many species detected at Poplar River First Nation, such as:

- Bay-breasted Warbler

- Cape May Warbler

- Canada Warbler

- Blackburnian Warbler

How the collaboration began

“We first talked with the Guardians and community, and asked if they would be interested,” says Jeff.

Norway says the project is a good fit for his community. “One of our goals is to develop new research partnerships. Plus, the project builds on the monitoring work we have already been doing.”

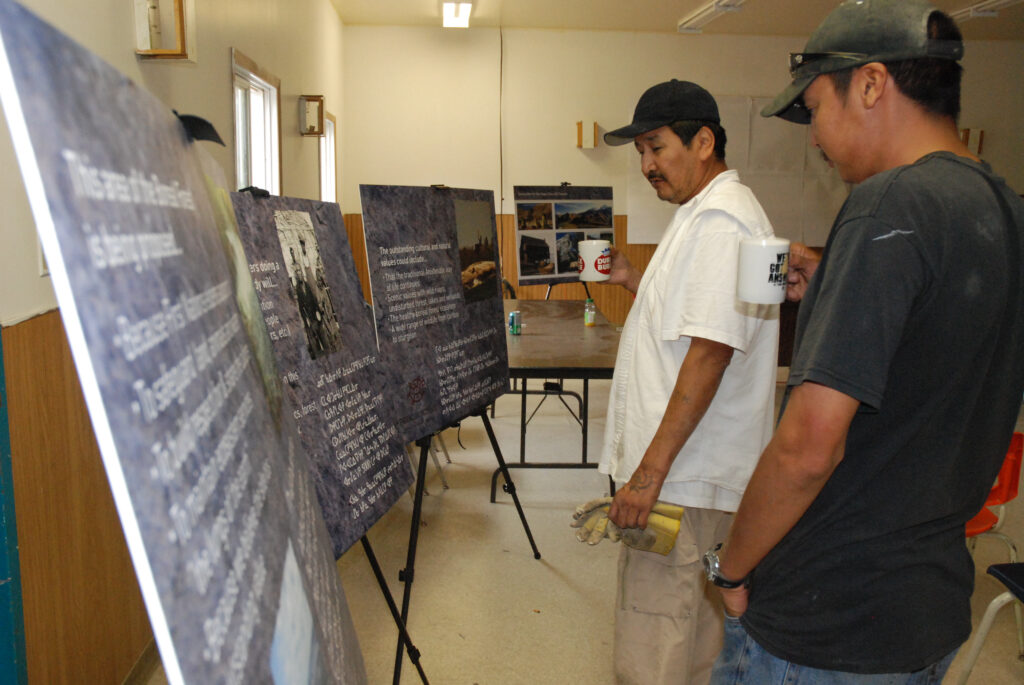

Indigenous Knowledge and Western Science come together

The Songmeter project relies heavily on Guardians, and the process of collaborating starts with listening and respect.

Listening to Guardians’ advice is crucial in a project like this, where Indigenous Knowledge and Western Science combine to create strong, respectful conservation efforts, says Jeff. “Things always overlay with Indigenous knowledge.”

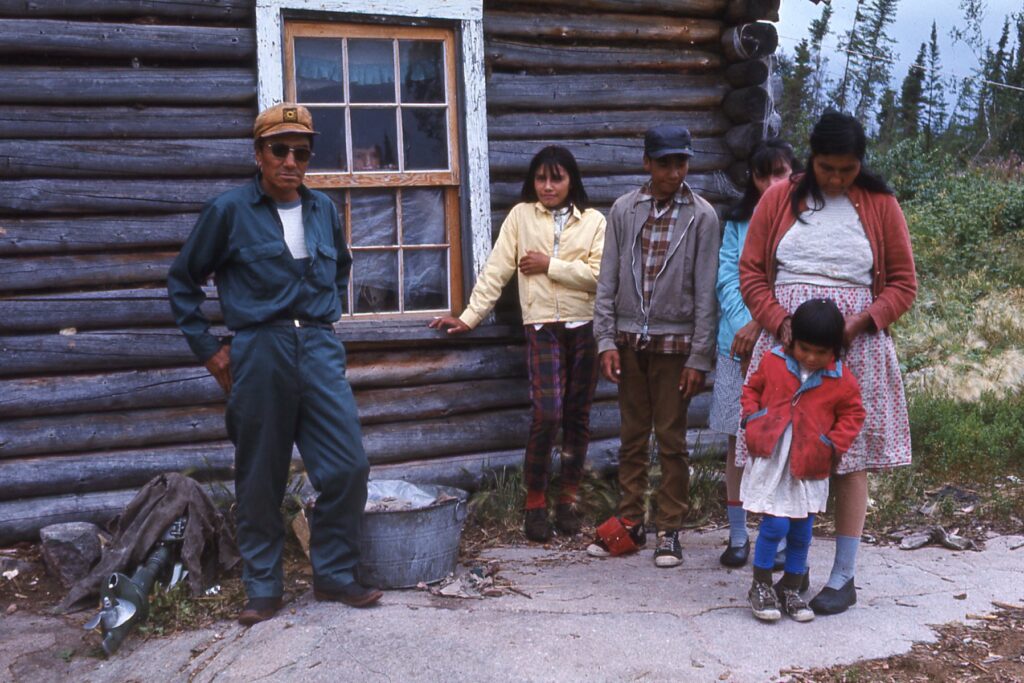

Guardians serve as stewards and scientists and are central to a program that pairs data collection with Indigenous ecological knowledge to track changes across the site over time.

Chad Wilsey, Vice President and Chief Scientist, National Audubon Society, in his blog about his work and experience in Poplar River First Nation

Guardians have a good understanding of the land and decide where to install Songmeters.

“Our Guardians’ hard work and understanding of the land have contributed to the project’s success,” says Councillor Eddie Hudson. “We are proud of the work they do.”

Songmeters last for a long time between battery changes. Recordings are saved onto SD cards for researchers to analyze.

The project continues

This past year, Guardians installed Songmeters in the same four locations as 2016. The 2017-2021 recordings have yet to be formally processed but since the start of the project, the number of species the team has identified has “greatly expanded,” Jeff says.

Thousands of hours of song

Analyzing bird sounds can be a difficult and time-consuming task.

“What happens with this kind of work is that you can get thousands of hours of recordings, and you can imagine someone sitting down and listening… You can only get through so much,” says Jeff.

The relatively small team picked random samples, listening to four 10-minute recordings from each day collected in 2016.

187.3 hours of recordings were sampled between May 27 and July 1, 2016

Birds of Poplar River Project – First Results

New technology to speed up the process

Recently, the team implemented BirdNET in their identification process. BirdNET is an artificial intelligence algorithm developed by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. This bird identification machine can quickly go through recordings to identify specific bird species.

The team will use BirdNet to help identify the recordings taken in Poplar River First Nation from 2017–2021.

Looking forward

In the upcoming year, National Audubon Society and Poplar River First Nation Lands Guardians Luke Mitchell, Brad Bushie and Youth Guardian Aiden Heindmarch will work together to expand the areas where Songmeters are placed. They plan to set up Songmeters in deeper and more remote areas of the forest.

“One place takes a couple of days to get to by boat,” Jeff says. “It’s exciting to see what we might find in these places.”

He hopes that over the years more First Nation communities can use Songmeters when developing their monitoring programs. He also hopes for more collaborative initiatives with communities in Pimachiowin Aki.

“If that’s what communities want to be a part of,” he says, “there are a lot of interesting things to discover.”