By Ray Rabliauskas | Photos: Jesse Belle

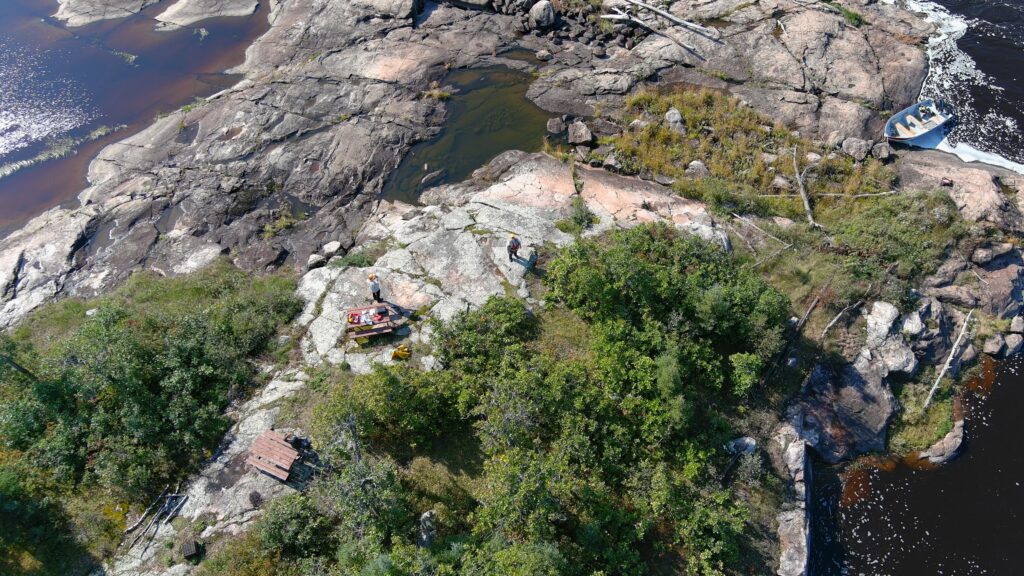

This past summer our Lands Guardian Program started a Community-Based Monitoring Project. We are collecting data using drones to monitor Lake Winnipeg algal blooms and shoreline erosion as well as testing water quality in the Poplar River that may affect fishing harvests and access to fishing grounds within Poplar River Traditional Territory.

Poplar River First Nation is moving towards becoming self-reliant with monitoring lands and waters by combining both scientific methods with what is already known—Elders’ Traditional Knowledge. We understand the importance of having the best information available so we can make good decisions in regards to our lands. Poplar River First Nation also understands the importance of having our own people with skills and equipment to do this work ourselves.

The Monitoring Program will provide learning opportunities for youth from our Elders and scientists so they can continue and expand the scope of this work for years to come.

We have hired Brad Bushie as part of our Community Based Monitoring Project.

“My name is Brad Bushie. I am from Poplar River and I am 24 years old. I have been working on and off for several years with our Lands Guardian Program. I have been hired full time to work with our drone to monitor the effects of climate change. I have received my certification as a Drone Pilot with a limited licence. This means I can operate our drone in uncontrolled airspace. I have almost completed training and studying to receive my Advanced Drone Pilot Licence, which will allow me to fly the drone anywhere in Canada. I love this work. It’s good to work with our Elders and the drone is a very cool instrument; it’s like a live video game.”

Brad Bushie, Poplar River First Nation

We are happy to share and highlight the work of our very competent Lands Guardians’ Team. As a community, we are very proud of these young people and the work they do.

Poplar River First Nation Lands Program

The following reports summarize the main field activities conducted and data collected during years two and four of the project: