Birds have always been an eye in the sky above Pimachiowin Aki. Now, thanks to drones provided by environmental consulting and research firm ECOSTEM, Pimachiowin Aki Corp. has an eye up there too.

We are working with ECOSTEM to map land and water habitats in Pimachiowin Aki as well as tangible cultural features found mainly along major rivers in the area. At 29,000 square kilometers, Pimachiowin Aki is simply too large to ‘see’ from the ground. Each drone, and its pilot are giving us a close-up look at areas we want to know more about.

“The project will enhance our understanding of Pimachiowin Aki and provide a baseline for monitoring,” says Pimachiowin Aki’s Executive Director. “Our monitoring program is part of how we fulfill our responsibilities as a UNESCO World Heritage site,” she adds.

Working with ECOSTEM will also allow us to bring all data we have ever collected into one place—a digital map of Pimachiowin Aki. People will be able to search the map for answers to questions like: Where do lake sturgeon spawn? What areas have been affected by wildfire? Where are the best places to find blueberries?

What exactly are we mapping?

| Habitat Mapping | Cultural Feature Mapping |

| Land habitats such as forests and grasslands, wildlife habitats such as caribou calving areas | Archaeological sites such as places where stone was collected to make tools |

| Water habitats such as rivers, wild rice, and wildlife habitat such as lake sturgeon spawning areas | Harvesting sites such as hunting and fishing areas, traplines, and berry and medicine plant gathering areas |

| Parts that form each habitat such as plants, soil and rock | Cultural sites such as cabins, campsites and petroforms |

Collecting Data from Soil to Sky

ECOSTEM collects vegetation, soil, and environmental data from plots

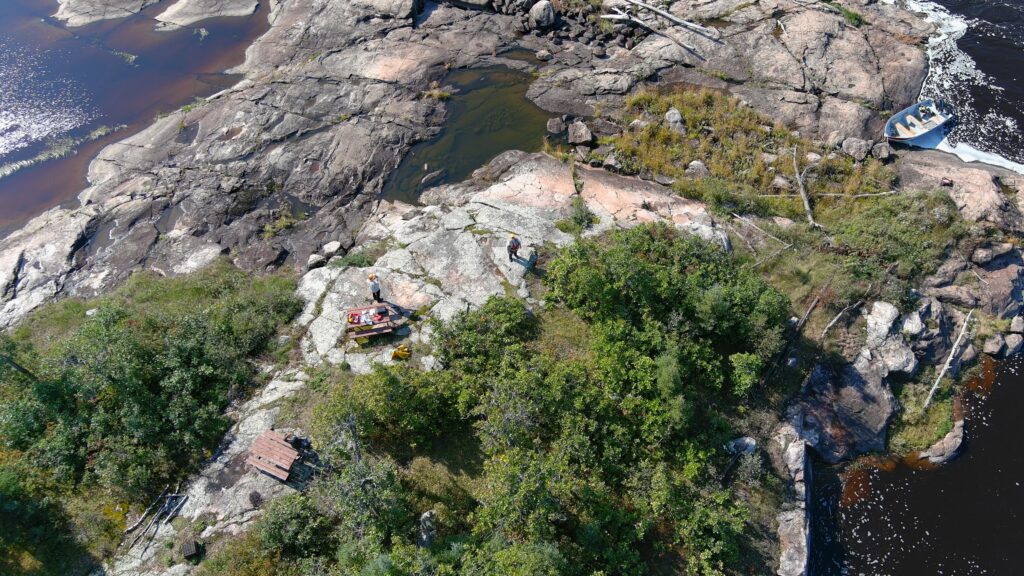

Aerial photo captured by a drone

Mapping is like taking inventory—in this case, identifying the location, number and kinds of habitats and cultural features in Pimachiowin Aki. ECOSTEM is taking inventory by going out on the land and water to collect samples and take photos and notes. The drones are capturing photos and video.

ECOSTEM Senior Ecologist Dr. James Ehnes says that the ECOSTEM drones collected “about 9,000 photos and 37 minutes of video” of Pimachiowin Aki this fall. “We had planned to capture considerably more photos and video but were unable to do so due to Covid restrictions, wildfire-related travel bans, loss of logistical support in communities that were evacuated, and extremely low water levels on rivers.”

Once we have our complete ‘inventory,’ Pimachiowin Aki can track changes over time. This is where monitoring comes in.

Monitoring is like giving Pimachiowin Aki a regular checkup—we will compare new information with our original inventory to keep watch on Pimachiowin Aki’s natural and cultural health. This will help us make sense of any changes and predict and prepare for any threats.

Project Q&A

We gained insights on the project through an interview with Dr. James Ehnes of ECOSTEM:

Your work with Pimachiowin Aki began in 2011 when you completed an ecosystem analysis to show how the area met UNESCO World Heritage criteria for outstanding universal value. What is different about the work you are doing today?

The ‘feeling’ has changed from conducting an academic exercise to having the opportunity to serve Pimachiowin Aki, its partner communities and local people. The work that we are now doing is focused on providing data, information, maps and other things that will support the continuation of Ji-ganawendamang Gidakiiminaan.

Pimachiowin Aki Guardians are the eyes and ears of Pimachiowin Aki. How does this project enhance their work?

Guardians can only cover a small area each year. The project immensely expands the area where information is obtained and can prioritize areas that we should go to get more information.

How are Pimachiowin Aki Guardians and Elders involved?

Land use information from Guardians and Elders is extremely important for cultural and natural features mapping, such as where are the best places to go to find certain plants and animals, where are notable culture features and sites located (e.g., petroforms, meeting areas, hunting areas, wild rice plantings, controlled burns, spiritually significant areas). We hope that the information that is passed on will contribute to maintaining the memories of the people and communities.

What will data you collect tell us about Pimachiowin Aki now and over time?

Most fundamentally, it will tell us what vegetation, wetlands, landforms, waterways, etc. occur within Pimachiowin Aki at a much higher level of accuracy and detail than is available now. It will also:

- Show a local person new places where they could to go to find things that they want to gather or hunt

- Identify important habitats for species of high interest such as caribou, moose, and sturgeon

- Aid in making reliable predictions about species that are important to local people or conservation

- Contribute to safeguarding and recovering species of conservation concern within Pimachiowin Aki. Examples: data may result in expanded woodland caribou research and opportunities to research lake sturgeon

- Detect and monitor the spread of invasive species

- Show people how their traplines have been affected by wildfire

- Identify areas that were burned more severely than usually happens—vegetation recovery may be limited, and it could be evidence that important, adverse climate change effects are happening in Pimachiowin Aki

- Help us study how Pimachiowin Aki is responding to climate change

- Show us areas that store the most carbon, areas that are most susceptible to releasing greenhouse gases as the climate warms, and the best places to do climate research

- Inform us if climate change is making fire effects worse, which has future consequences for what will be found on the land and in the water

- Contribute to fulfilling UNESCO World Heritage monitoring requirements

How exactly do you collect information for the maps?

We collect information in two ways. We get information for the entire site from satellite imagery and information that has been created by others (e.g., elevations). We go out on the land and water in Pimachiowin Aki and take photos and notes. Sometimes we do this from planes and other times while boating or walking. While on the land, we collect plot samples and use drones to collect photos and video.

What is plot sampling and how is it done?

We collect habitat data in plots, sometimes with a community member and sometimes on our own. For our work so far, this has been a 40 by 40 metre square plot. Within this plot, staff collect plant, vegetation, soils and environmental data. A botanist collects plant and vegetation data by walking through the plot and recording what they see. A soil specialist collects soil data by first digging a narrow hole about 50 cm deep, then using an auger to go down to about 100 cm and pull up material that is examined and used to describe soil conditions.

We try to leave no trace that we were there. When we’re done, we fill the hole and replace the surface ‘divot’ that was carefully removed before digging the hole.

Why has the drone collected more photos than videos?

We focused on photos because we expected that they would be more useful for creating the habitat map for the entire site. An advantage of photos is that they can be ‘stitched’ together to create an image that shows a much larger area. The stitched image from the drone is more magnified than Google Earth. We may lean more towards video when documenting cultural features along waterways or habitats for species that are especially important to local people.

How does monitoring a habitat make it possible to reliably monitor a species?

A species’ habitat is the most important thing that determines how many individuals of that species can exist within Pimachiowin Aki, and where they are likely to be found.

Using moose as an example, areas that have burned in the past five to 15 years tend to provide considerably more moose food per hectare than other areas. If the proportion of Pimachiowin Aki area that has burned in the past five to 15 years goes up, the number of moose can also increase.

Using sturgeon as an example, this species has very specialized conditions for spawning. By mapping spawning conditions, we can identify areas that should not be disturbed by human activities. We can also use the mapping to identify locations that are good candidates for restoring suitable sturgeon spawning conditions.

See our infographic to learn more about how forest fires affect moose

Learn how to identify and protect lake sturgeon

Drone captured data

Bing satellite image

How close do the drones get to wildlife and people?

Manitoba wildlife regulations prohibit harassing wildlife, so we maintain the distance needed to avoid that, which varies with species and individuals. If we saw behaviours indicating an animal was being disturbed, we would quickly move further away. Our drones are very quiet and with the cameras we use, we don’t need to get close to an animal to see it in high detail.

We don’t intentionally get close enough to identify a person unless they have provided their consent.

What excites you most about the project?

I’m very excited by the amount of detail that can be obtained with a drone. We can create 3D images of an area, which will be very impressive for things such as depicting cultural or natural features on waterways.

When will the map be complete and where can I find it?

The map should be complete in 2023, following another field season in 2022. ECOSTEM holds the data and information for the map in trust for the Pimachiowin Aki communities. Because the map and derived products contain confidential information that belongs to the communities, they may only be used with the express and prior permission of the communities.

Photos: ECOSTEM