As the fall moose harvest approaches, Pimachiowin Aki wants to remind community members and all hunters to help Guardians during this busy time. If you see any waste, reckless hunting, or hunters being disrespectful, tell your Guardian. Guardians will, in turn, report concerns to their communities and to provincial staff.

Moose Population

Pimachiowin Aki is communicating with our provincial government partners to renew our working relationship and talk about the moose population and concerns about harvesting.

“We want to be part of the decision-making process. We want to be part of the consultation and plans,” says Pimachiowin Aki Director William Young, Bloodvein River First Nation.

Having conversations and sharing information with government partners will allow us to make the best decisions for the moose, adds Pimachiowin Aki Executive Director Alison Haugh. “How are moose doing in the area? Do we need to close areas or limit the hunt because moose are not doing well? If they are not doing well, is it due to habitat or hunting pressure? These are important answers to have.”

Watch for updates on our work with wildlife and habitat.

Did You Know?

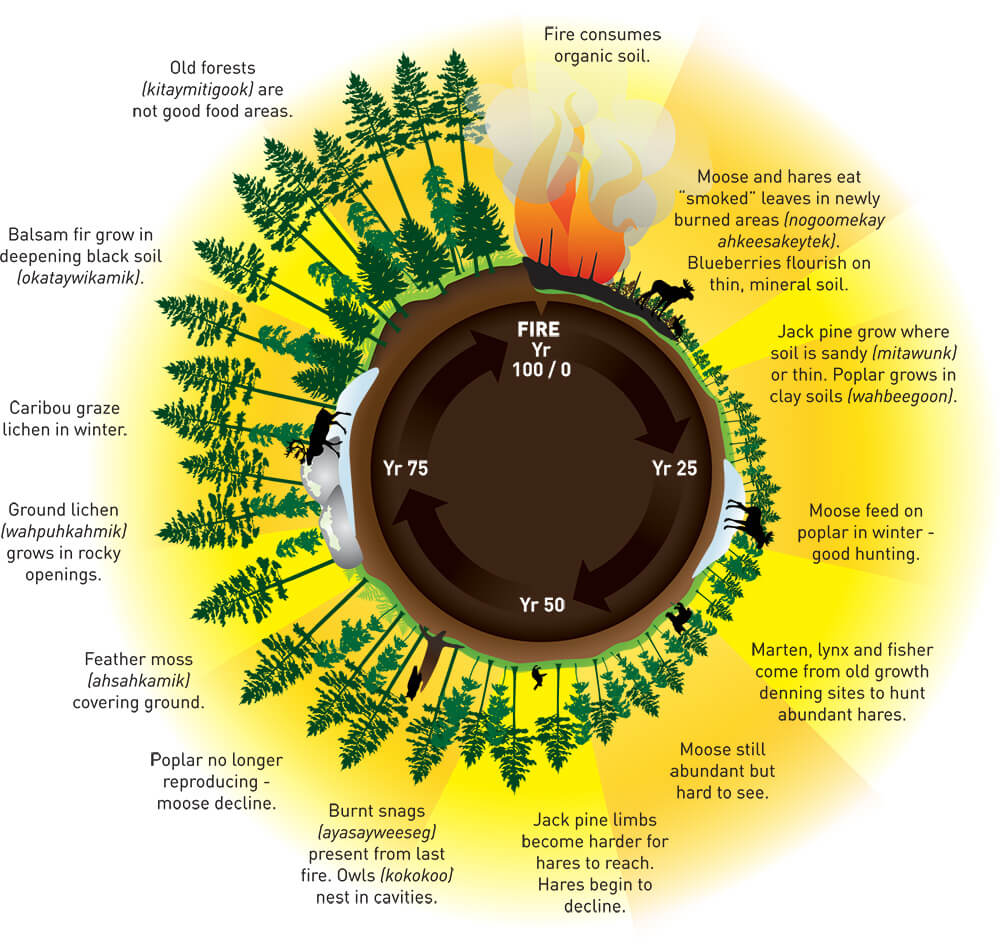

Most of Pimachiowin Aki is caribou habitat, but because of the wildfire cycle, we could see more moose in five to 10 years from now.

Photo: Ōtake Hidehiro