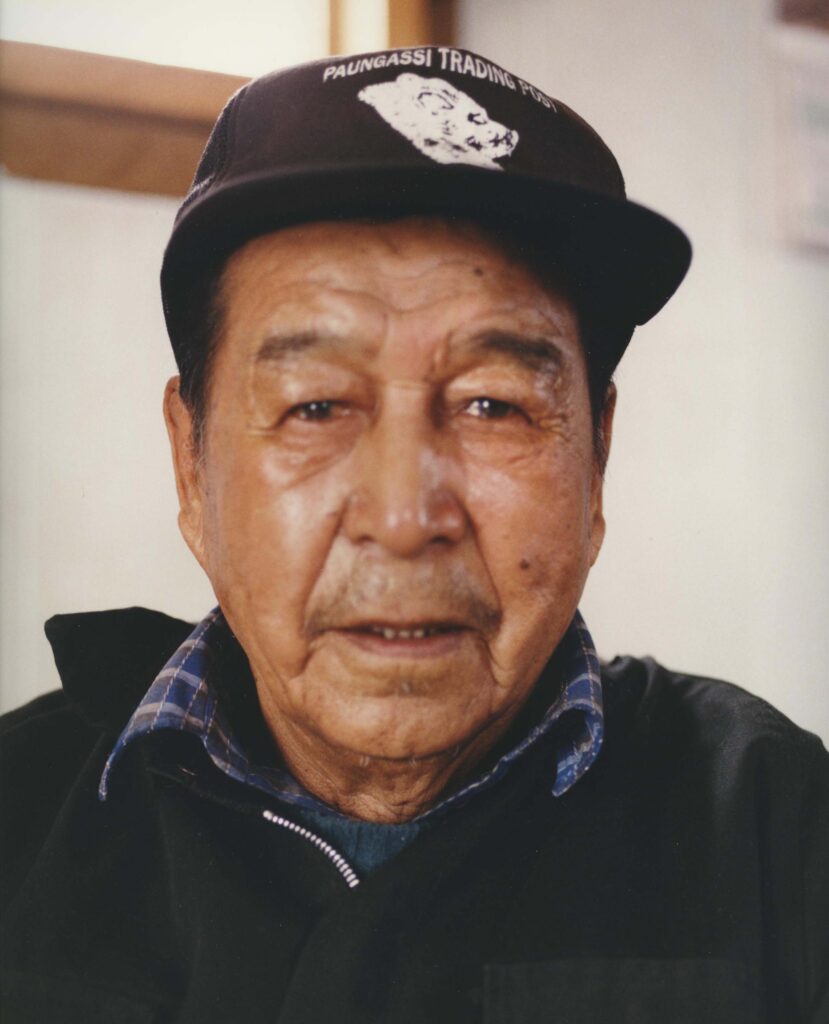

By Naomi Moar, Little Grand Rapids First Nation

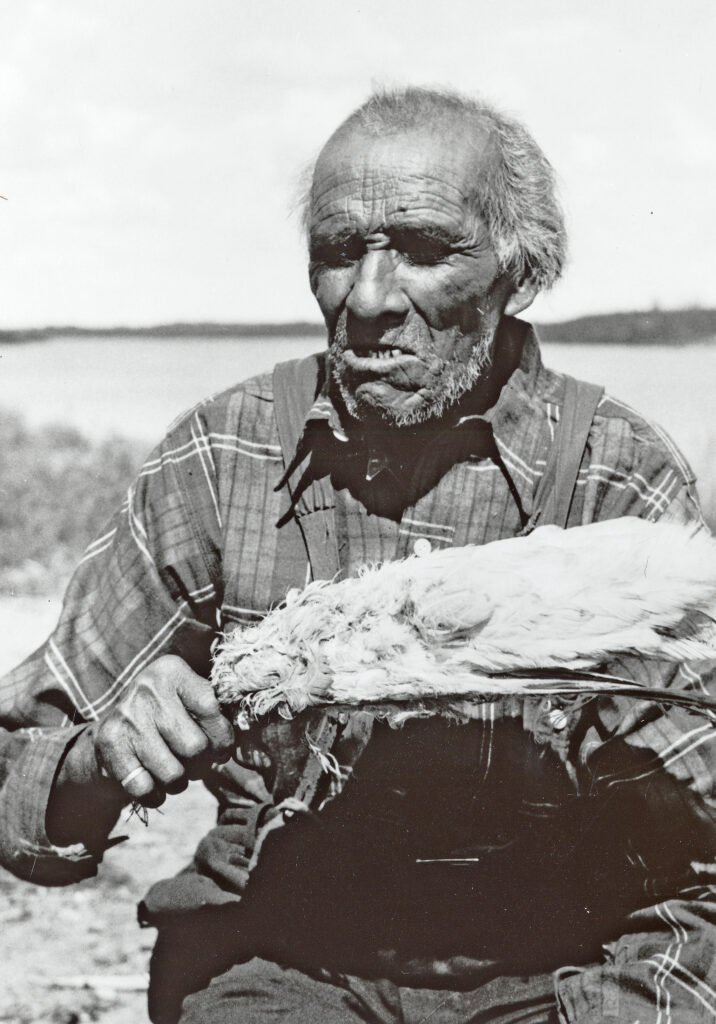

Preparing meat for smoking takes days. After the quarters are prepared and cut up, and undesired pieces are cut off, the meat has lost approximately 1/4 of its weight. All the sinew and fat are cut away.

Cutting the Meat

Each chuck is cut down the middle and then along the ‘bottom’ to create a 1/8 inch thick slice. As you cut along the bottom, you are unfolding the meat to prepare a long piece for smoking.

Depending on how many sticks you have made for the smoke shack (I usually make five), you can smoke a whole hind quarter in about six hours depending on the thickness of your cut.

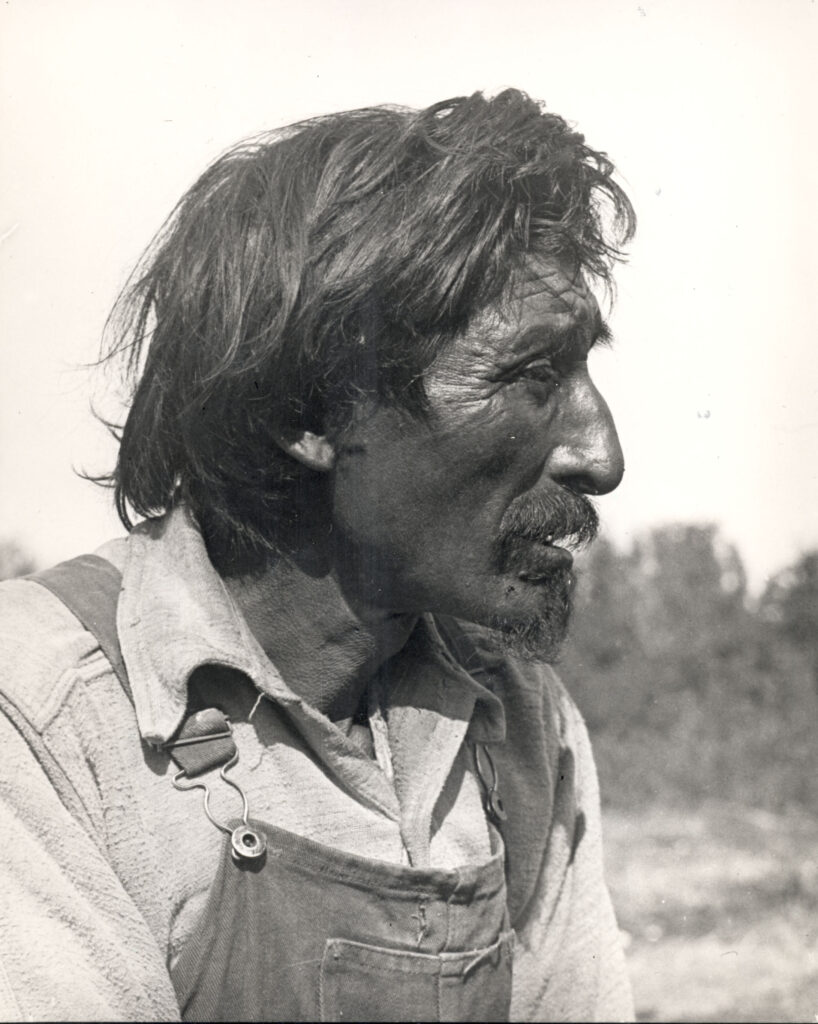

Naomi Moar, Little Grand Rapids First Nation

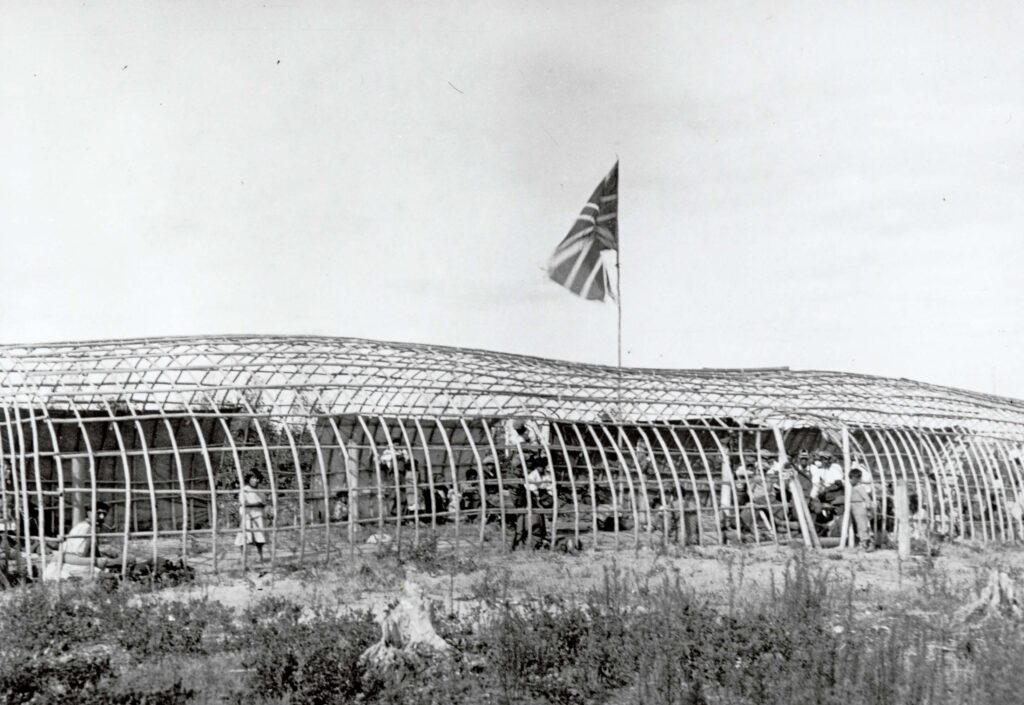

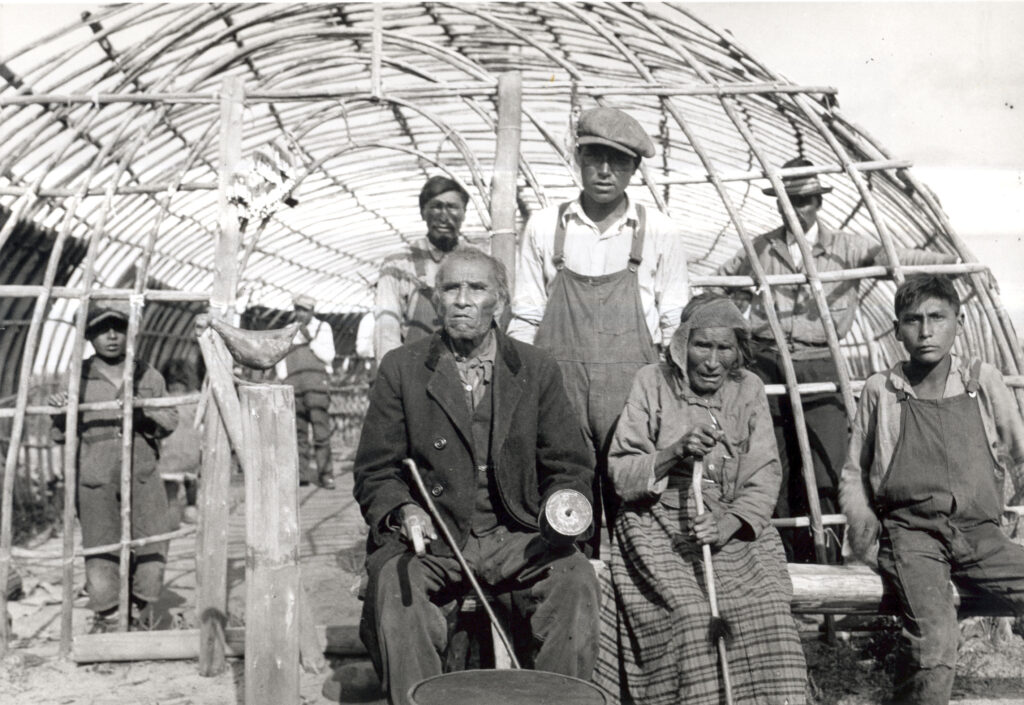

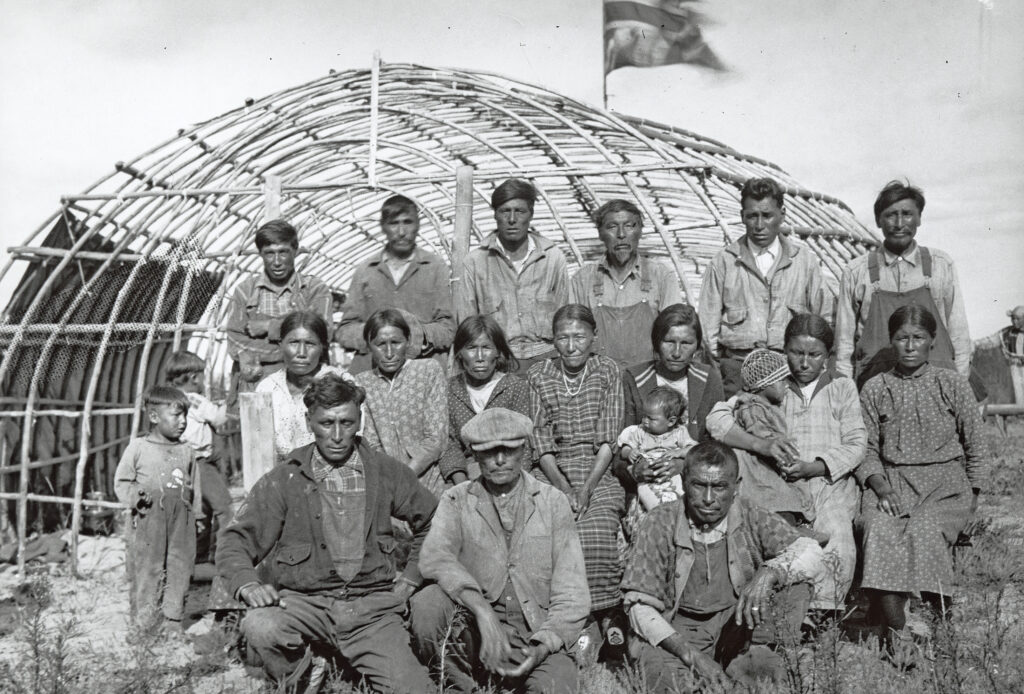

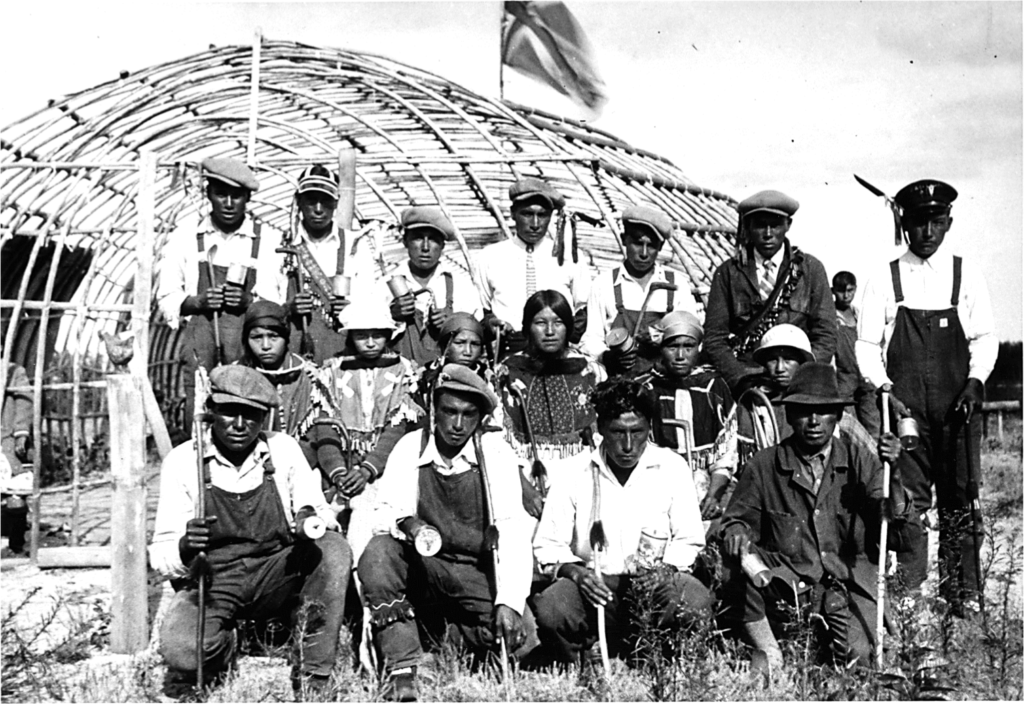

The smoke shack

This is where you will hang your meat. The smoke shack is made of red willow (after it turns white) for the frame and cooking rods.

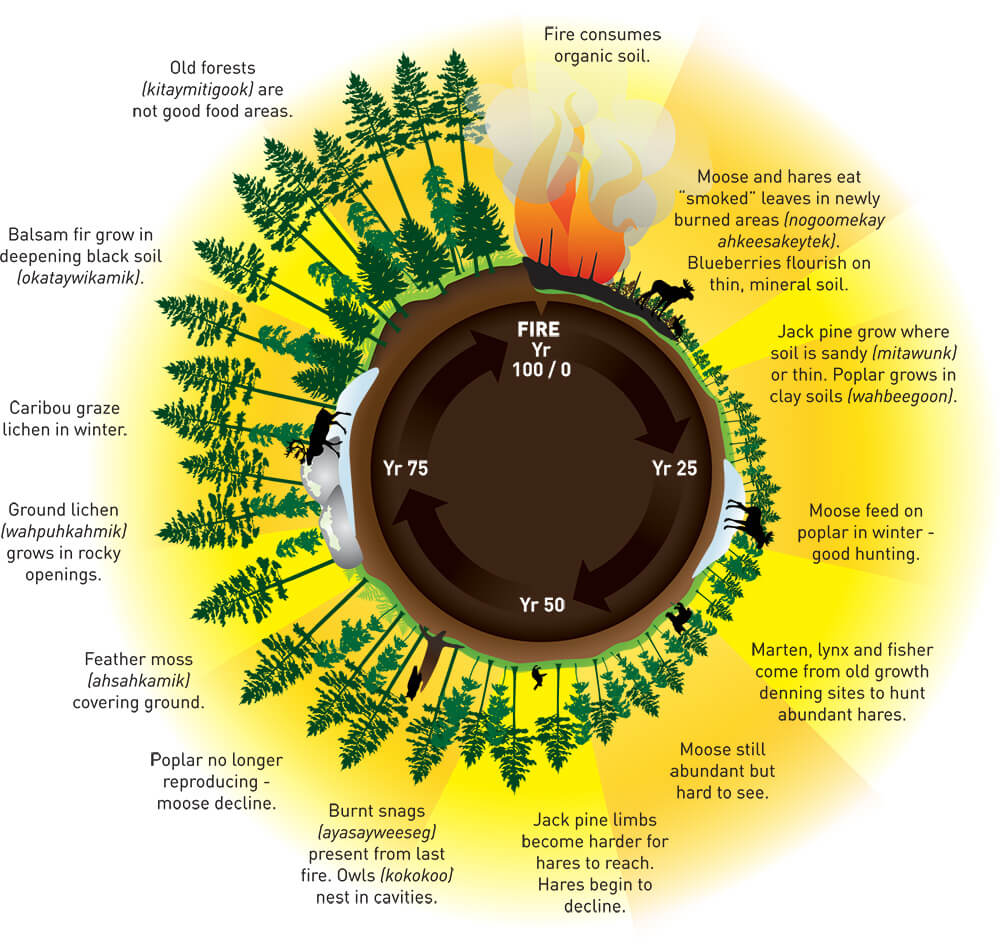

The wood, fire and time

The wood to burn is poplar. The fire cannot be too high otherwise the meat will burn. Because we are removing the moisture from the meat, the session should take about six hours at a low burn.

Because of the cost of fire-retardant canvas, I have yet to procure one.

Everything I have learned, I learned from my grandmother.

Photos: Naomi Moar

Shop

Shop