When young people go out on the land, they come back with their language.

—Anishinaabe Elder, in translation

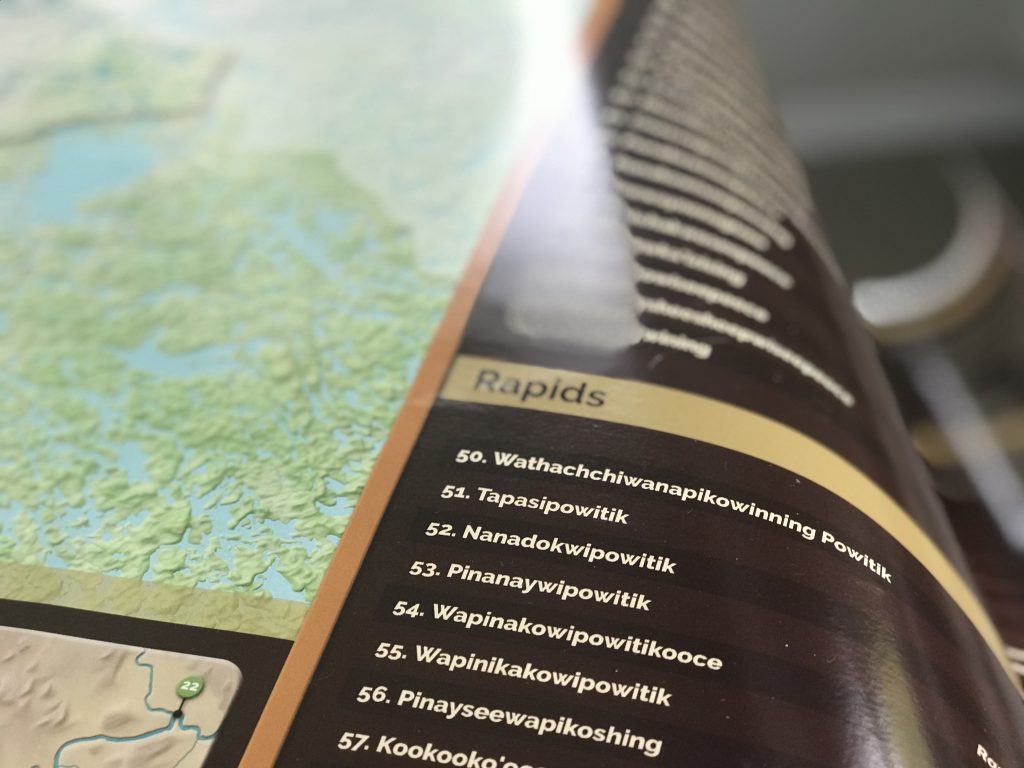

This summer, eight youth had a one-of-a-kind experience using the Poplar River First Nation Traditional Place Names map. The teens participated in a five-day knowledge-sharing trip hosted by Poplar River First Nation Guardian Norway Rabliauskas and his mother Sophia. Together, with hired guides, the group boated from the Poplar River First Nation community to Pinesewapikung Sagaigan (Weaver Lake). Along the way, they manoeuvred through 13 rapids marked on the map, and translated the names into Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe language).

With names like Thagitowipowitik (Rapids before Poplar River flows into Weaver Lake) and Machi-powitik (Bad rapids where some people sense bad feelings), the map prepared them for the rapids ahead. It also helped them reflect on the past.

“I think it’s important for the young people to learn whey where they come from, and the history of Pinesewapikung Sagaigan (Weaver Lake),” Norway says.

The map gives meaning to places and helps keep the language and stories about these places alive. Do you want to view the Poplar River First Nation Traditional Place Names map, with 149 named places? Click here and scroll down toward the bottom of the page.

Learning the History of Weaver Lake

Cultural heritage connects people and unites communities. The group camped on an island, where more people from the community were already gathered. Together, they visited the healing camp near Weaver Lake to learn more about the history of their community, and why the healing camp was established many years ago.

“We wanted them to know who went there, why the camp exists, and why it is important,” Norway explains. He and Sophia shared with the youth that some Elders in the community were residential school survivors who used this site for their own personal healing journeys.

Learning the Seven Sacred Teachings

Sophia also explained the principles of the Seven Sacred Teachings that have been passed down from generation to generation:

- wisdom

- love

- respect

- bravery

- honesty

- humility

- truth

Inspiring the Next Generation of Guardians

Anishinaabeg were placed on the land by the Creator and have a sacred responsibility to care for it, so the trip included a ride around the lake to see the offering rock and pictographs, with a hike up a high rock to see tea kettles (deep holes in rocks). The youth also learned about the trees in the area. Each youth received an information booklet.

“I wanted to create a spark that might inspire them to work as Guardians,” Norway says.

The youth will carry the land-based knowledge and skills with them into the future, he adds, noting that the youth prepared meals and helped around camp.

“They set up and took down the tents, too,” he says. “I wanted them to be involved as much as they could.”

Each youth had a journal to write down their own personal reflections.

“On the last day, we went fishing as a group and cooked our meal with the fish we caught,” says Norway.

Because the knowledge-sharing trip was such a success, Norway plans to make it an annual summer outing. “We’d like to make it bigger next year,” he says.

It was Norway’s work with the Education Department that inspired the trip, funded in part by Pimachiowin Aki. Norway facilitates a language and culture program that was cut short this past school year due to the COVID-19 school closures. He intends to continue the program in the current school year with the help of community members who speak Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe language).