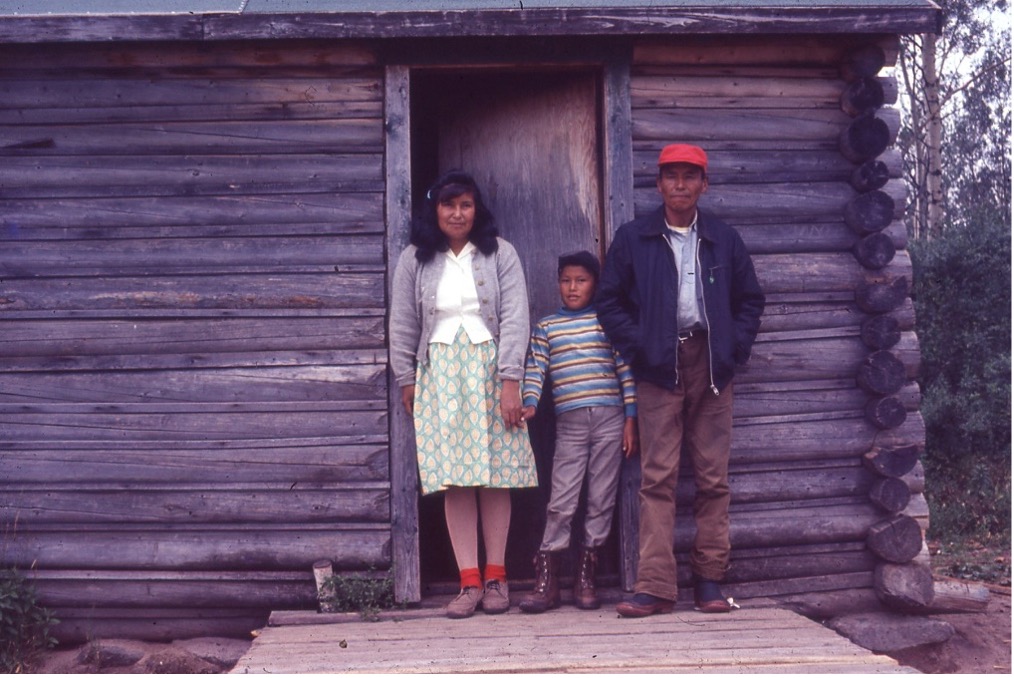

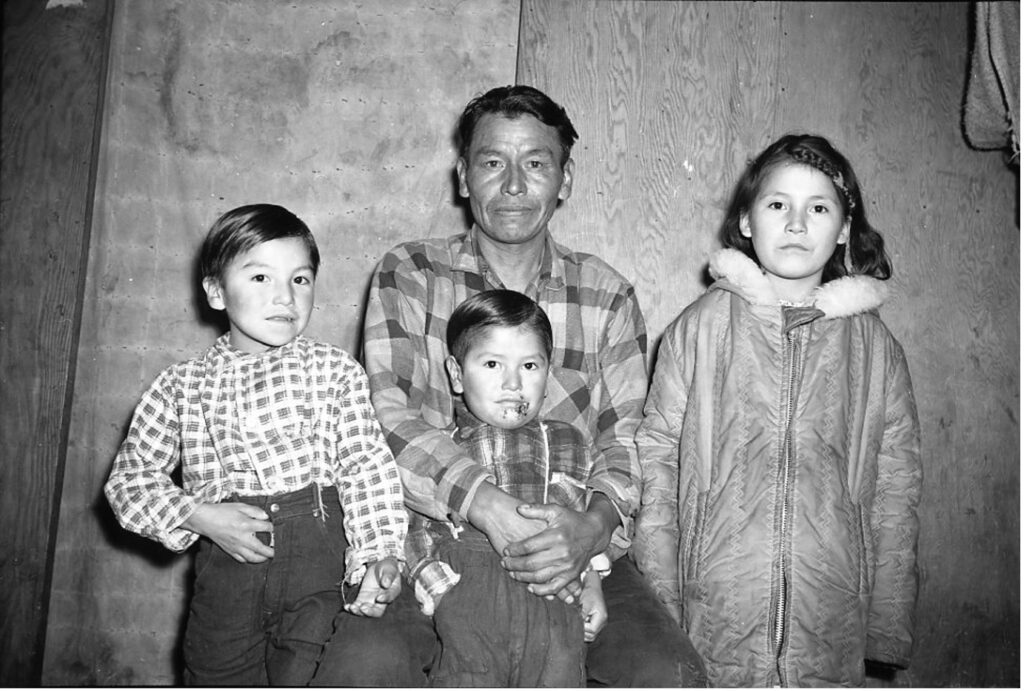

Notes & photos from nature photographer Ōtake Hidehiro

1. Thursday | Net Fishing, Sacred Rock & Plant Medicine

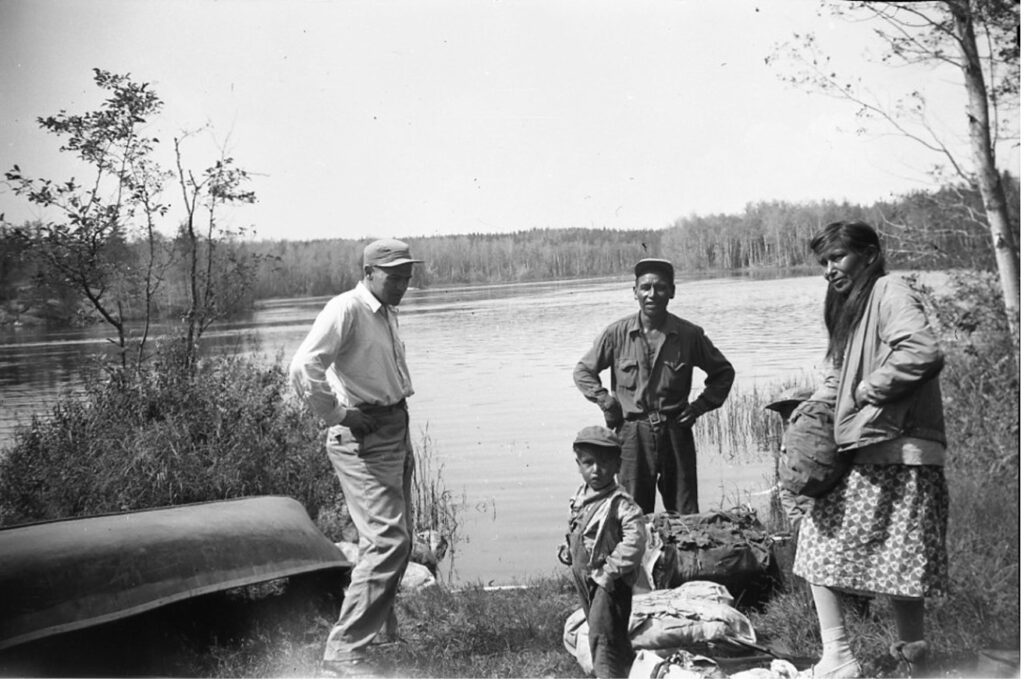

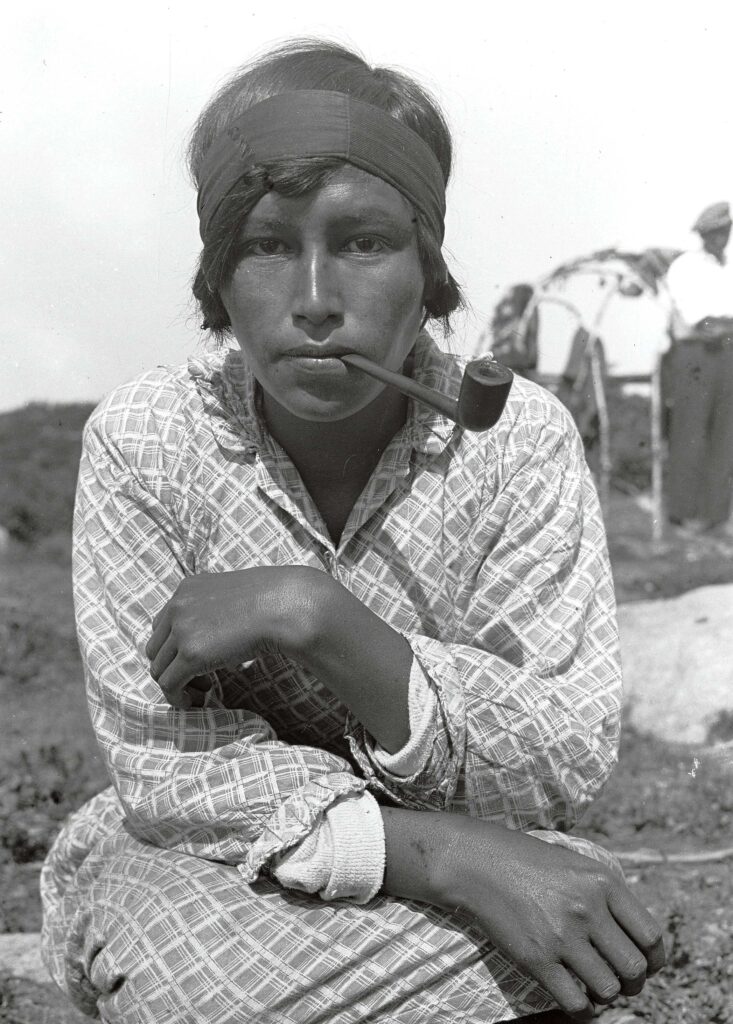

Colin and his wife Cora took me to set a fishing net. We boated for 4.5km to get to the netting point and put the net into water. The net was 40-50m long or so.

Colin took me to a sacred rock. He put tobacco under the rock. It should avoid the direct sunlight and wind so that it won’t blow away, he said. It is also a good hunting spot for geese. He showed me the blind made by rocks to hide the hunter from geese.

Along the shore Cora was collecting medicine plants. She took just the tip of the twig of the shrubs to get buds. “It is good for your heart,” Colin said. It has a minty, herby, refreshing taste!

Colin also tried to get a root of sweetflag from the muddy ground for medicine.

2. Friday | The Catch

Surprisingly, we caught many fish just for overnight! We kept 32 walleyes, two big northern pike and 14 whitefish. We put a net into water again. Colin and Cora were busy cutting fish even after dark! We went to get the net out from the water in the evening. We caught a few more fish to cut!

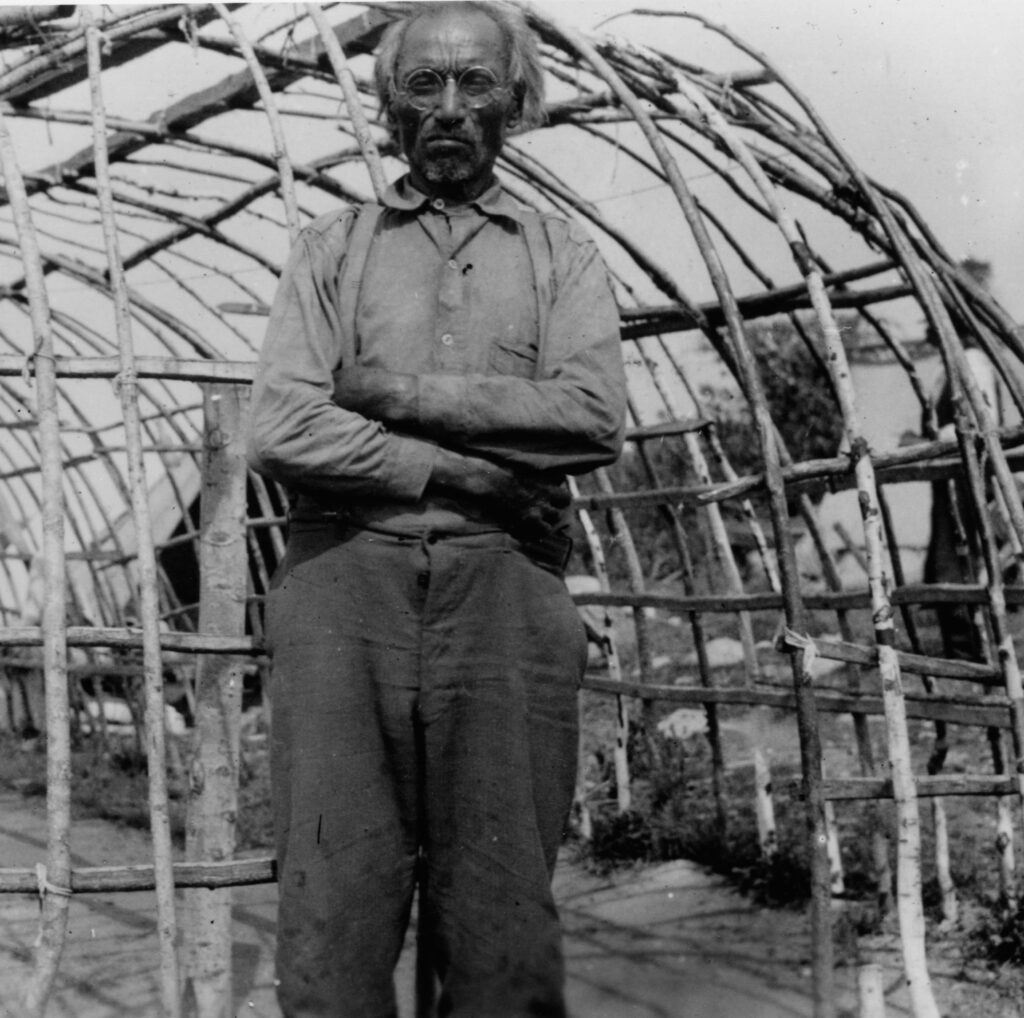

3. Saturday | Smoke House

Colin built a smoke house for whitefish with fresh green birch trees for poles. He carefully selected the right size of tree, which would easily bend and be strong enough at the same time.

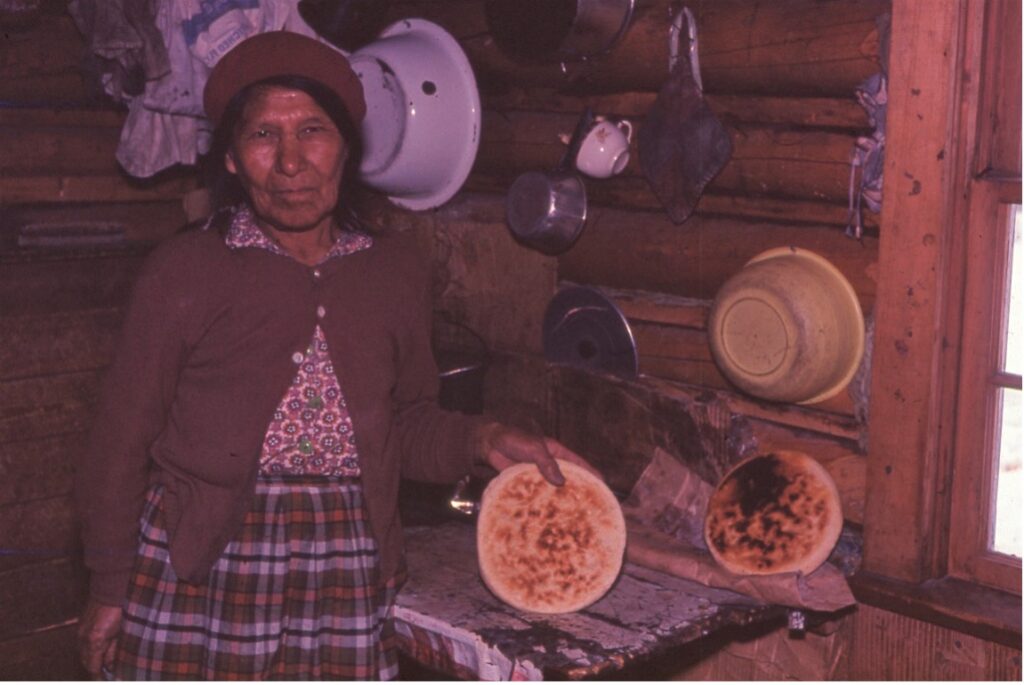

Cora cooked fried bannock and fish (northern pike) for dinner.

4. Sunday | Smoking Fish

Colin started smoking whitefish around 11am. He needs old aspen trees for the smoke. He prefers almost-rotten logs, which produce a lot of smoke. He kept feeding the fire and checking the condition of the frame and temperature. It took 6-7 hours to finish. He was checking the colour of the fish meat to know if it is done or not.

Cora cooked moose stew for dinner! It was so tasty!

5. Tuesday | Moose Call

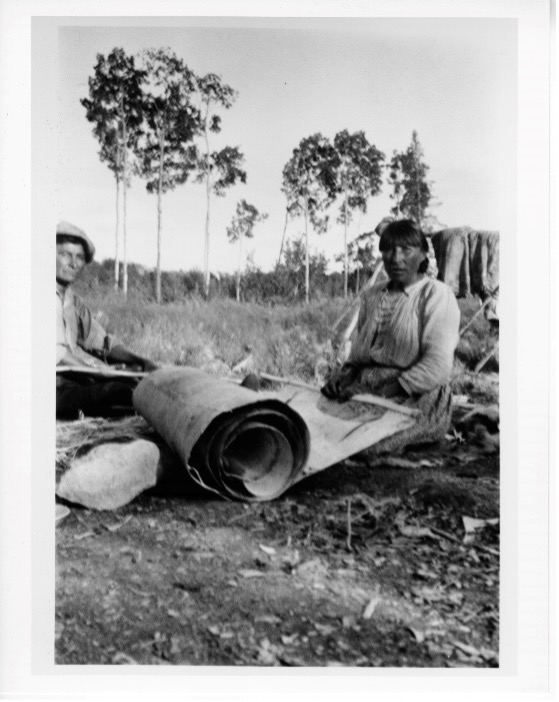

Today Colin showed me how to make a moose call out of birch bark. Colin looked for the right size tree around town but most of the trees were too old or too small. The moose call we made became a bit shorter than usual. After we made the moose call, we drove Colin’s truck to the edge of the town and tested it on a hill. “It should work. We will try it in the bush tomorrow,” he said.

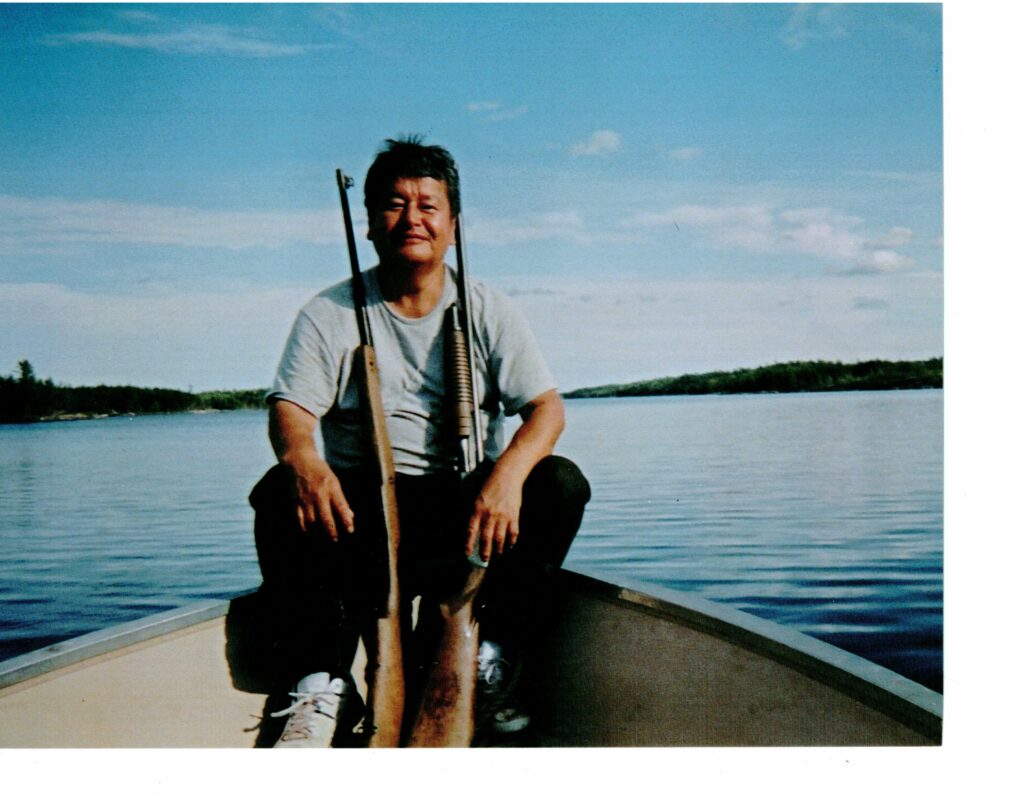

6. Wednesday | Boat Ride, Pictograph & Moose Call

Colin took me on a boat ride! We visited a pictograph. It was very interesting to see. Colin told me that looks like three turtles and some kind of animal below it.

He brought a shotgun and rifle in case we could see any ducks, geese or moose.

We tried to call a moose in two different locations and waited for quite a long time. Unfortunately no moose came out, but it was wonderful to learn the Anishinaabe way of life on the land.

Thank you for sharing your knowledge and experience with me, Colin!

Photos: Ōtake Hidehiro