Thank you to Clinton Keeper (storyteller) and Emily Thomson (transcriber)

Clinton Keeper shares this story told to him by his grandmother, Maggie Duck (Nenawan), who was told this story by her father, John Duck (Mahkoocens)

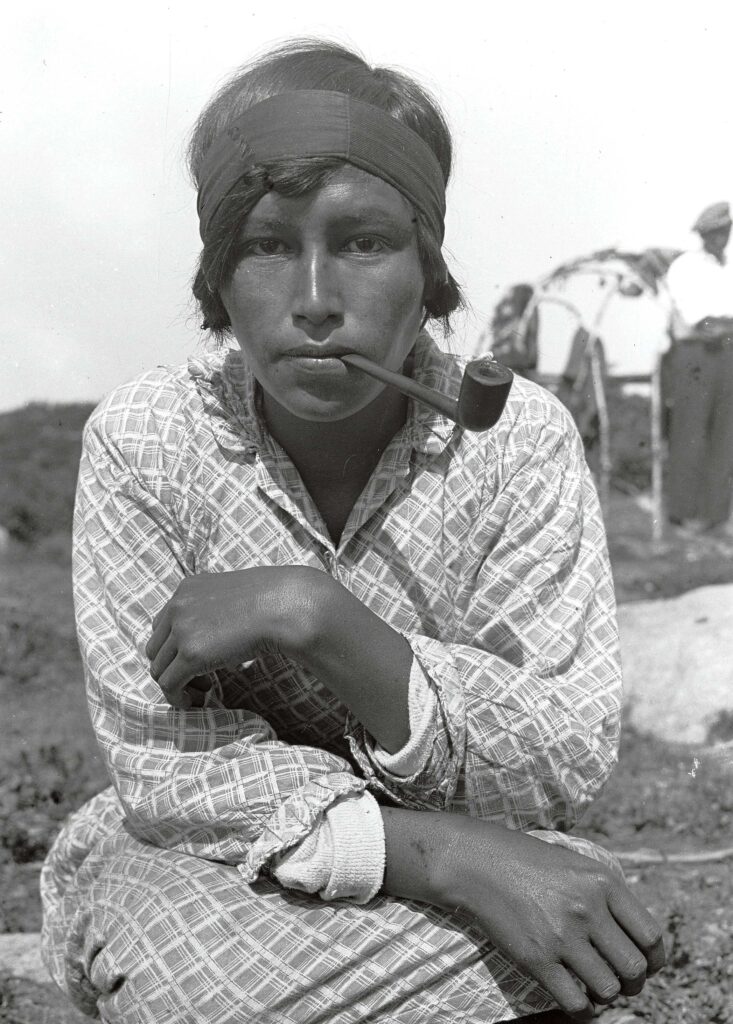

Photo: American Philosophical Society (Hallowell Collection)

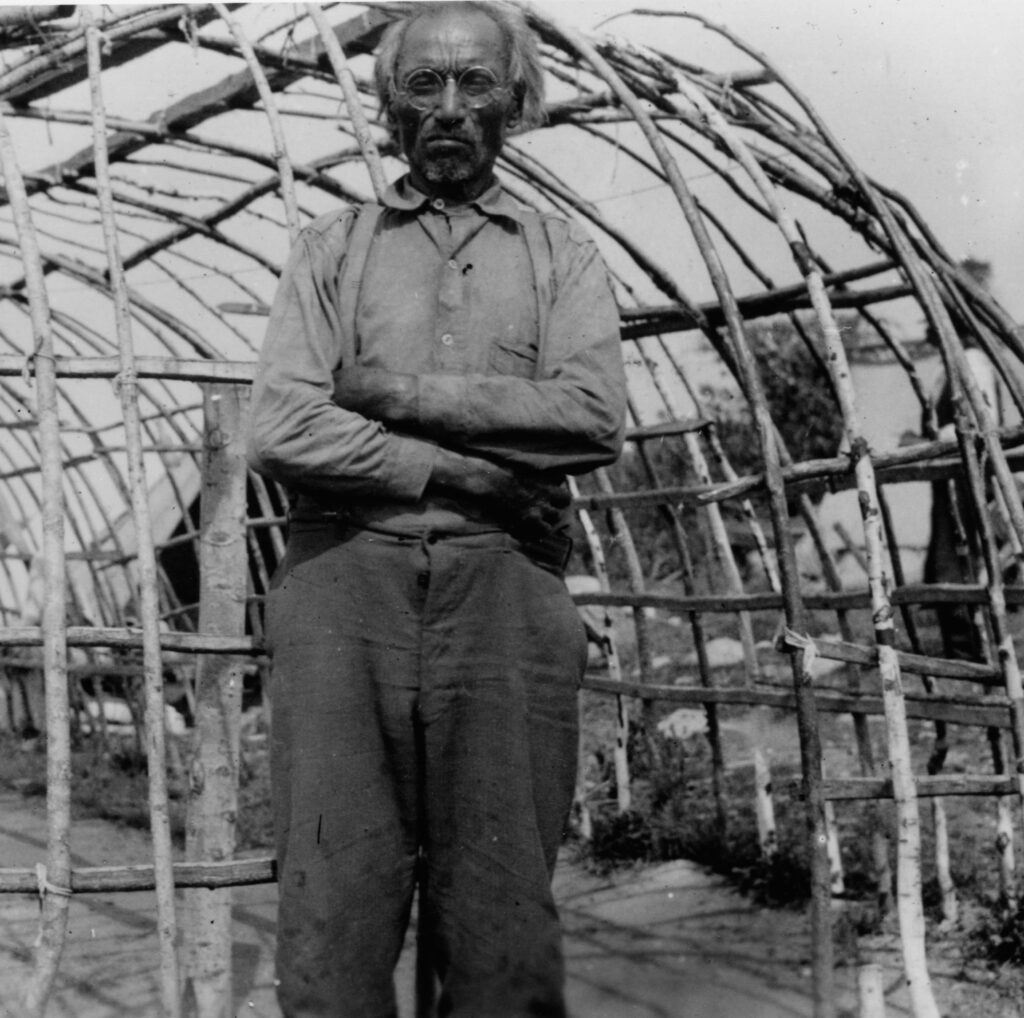

Photo: American Philosophical Society (Hallowell Collection)

It was a long time ago. There was a village. In that village, there was an orphan boy who had lost his parents and siblings, and all he had was his grandmother. Back in that day, you’d say they were one the poorest in the village. They lived on the outskirts of the village. They called that boy Waakeygan.

The kids would ask that boy if he wanted to play – he had no friends – but they just did that so they could pick on him. They would invite him to go play with them along the fire, but they would heat up these willow sticks, poke his legs, and hurt him. He was lonely and had nobody else to play with.

Later on, a Council of Elders and Medicine Men and Chief heard something was coming for them: it was Wiindigoo.

They heard through a ceremony that the Wiindigoo was going from village to village eating people. Wiindigoo is a spirit, a cannibal.

So those old people got together in the Chief’s lodge and wigwam, passing their pipe around… who’s going to challenge the Wiindigoo that’s coming? Every Shaman that sat around the fire didn’t have the gift to challenge the spirit, this being that was coming towards them. Finally, one of the old men said, “Somebody must know something. Somebody must have a gift. There has to be. We cannot just perish like that.”

As they were smoking there, one of the Elders spoke. “There’s a boy in this village, who is without parents and lives alone with his grandmother. Seek him out.”

So in the meantime, Waakeygan was with his grandmother in their wigwam and that old lady was working on tending to his wounds where those kids put those willow sticks on his legs. She was cleaning his wounds, and as that boy was sitting there, he told his grandma, “Hurry up. Wrap up my legs; they’re coming for me.”

He just knew something.

The old lady put medicine on his leg, wrapped it, and sure enough – the young braves opened the wigwam door and then they said, “You’re wanted. The Council of Elders wants to meet you, and the Chief.”

And he said, “I know.” The boy went with them; told his grandmother not to be scared.

So he went to go see them. And then, as soon as he walked in, before anyone could say anything, the young boy spoke. He says, “Move the village. You go down west. You will come across a lake and you’ll stay there. No matter what you hear, do not come to the east. Tell everybody I will come.”

So that morning, they dismantled the whole camp and they all moved west. The boy took off in the opposite direction, to the east, to meet this spirit or entity. When he got there, he got to a big lake and he went to the centre of that lake and he stood right there, and he could feel the cold, cold breeze coming. It was bone-chilling cold there. And then when he looked across, he could see trees swaying in the distance – something big is in that forest.

He could see snow falling off the trees. Then all of a sudden, he sees something coming out of the bush and onto the lake. It was massive; it was as tall as those trees. So that boy, he stood there. He stood his ground on the ice facing that thing that’s coming.

And then that thing, Wiindigoo, yelled. He looked up at the sky, and he yelled a loud cry. Wiindigoo just got big.

That boy yelled out a big war cry, and the little boy just got big; even bigger than Wiindigoo.

Then Wiindigoo did the same thing again; he just got bigger and bigger. Then the boy did the same. He got bigger and bigger. They did this a few times until they were really, really big.

And then, they started fighting. All of a sudden, that boy grabbed Wiindigoo and threw him on the ice. Have you ever heard a rock being dropped on a fresh lake and dooo (reverb sound). That sound. You just hear that. Where that village was, where they were camping, where they moved, they could just hear the sound of the ice and they could hear that sound, like thunder.

They were saying, “Oh, my, they’re fighting already.” They could feel the ground vibrating off and on. They see light sparks in the east. Then all of a sudden, it went quiet.

So those old people, those Council of Elders were sitting around a fire in the Chief’s wigwam. They were smoking their pipe and then all of a sudden, they heard a big thump right outside the wigwam.

They opened the door and there was a big giant toe outside. That boy was standing right there beside that big giant toe. That was Wiindigoo’s toe.

He had natural gifts, that kid; spirits that watched over him. He become a great warrior for his people.

This is the story that was told to me by Maggie Duck. This is the way I tell it, how it was told to me. It is important to keep the story in its original form.

The lesson of the story

What I learned from there is to respect people no matter who they are, no matter how small they are. You know? We don’t know what watches over people. That’s why it’s always important to respect people when you meet them because you don’t know what carries them or what watches over them. It’s not the person that you offend. That person may forgive you but the one that’s watching over that person may not forgive you. That’s why it’s important that we always talk polite to people. Even when we travel, we always travel with tobacco and offerings out of respect.

Feature Photo: Hidehiro Otake