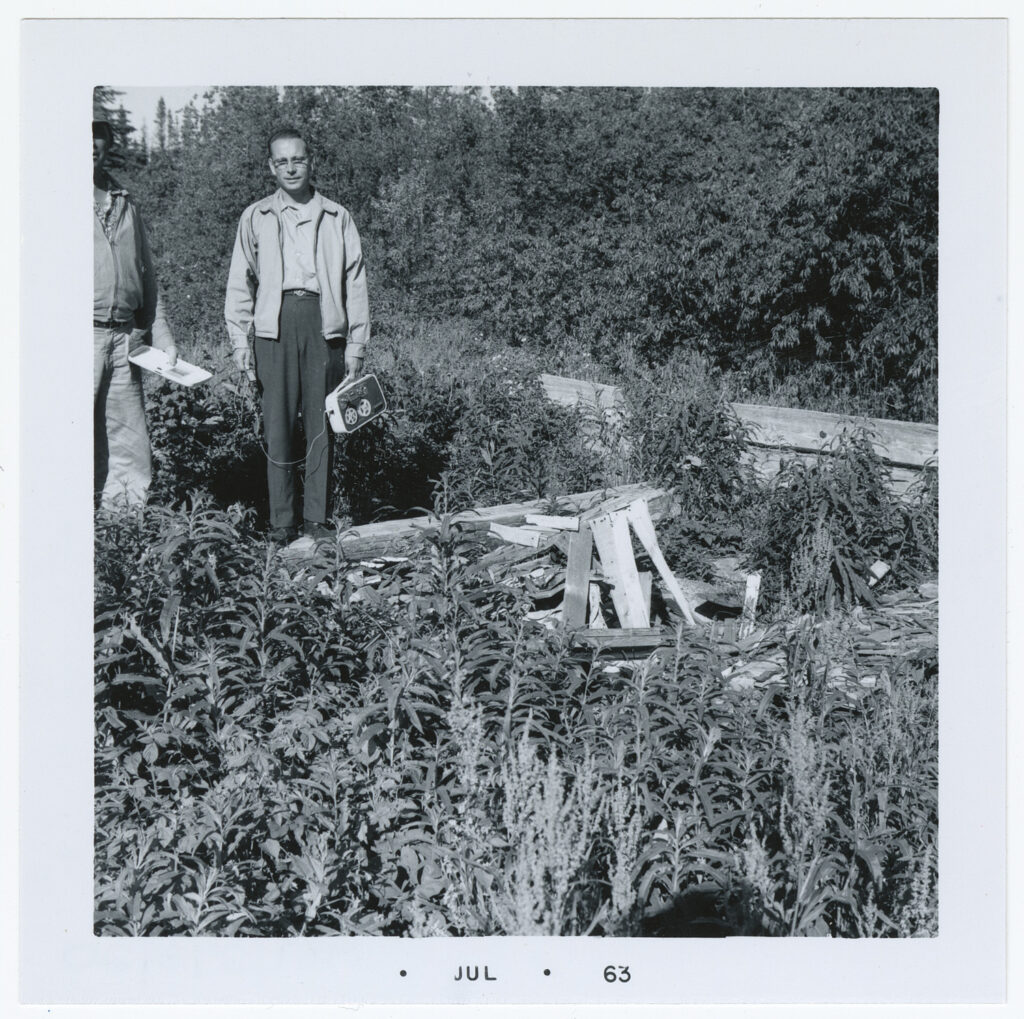

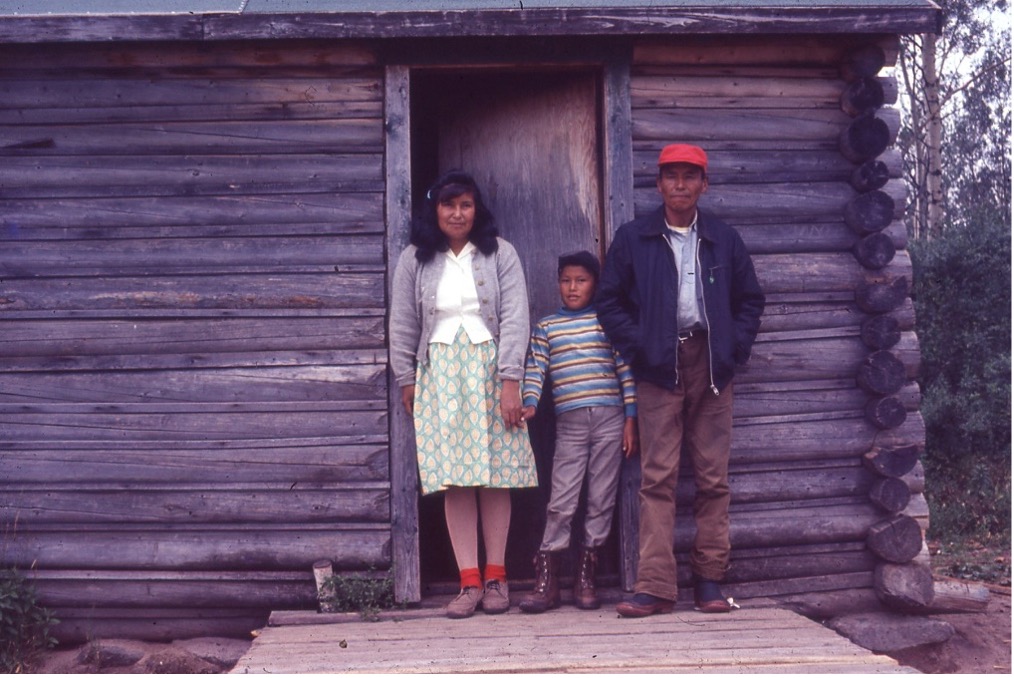

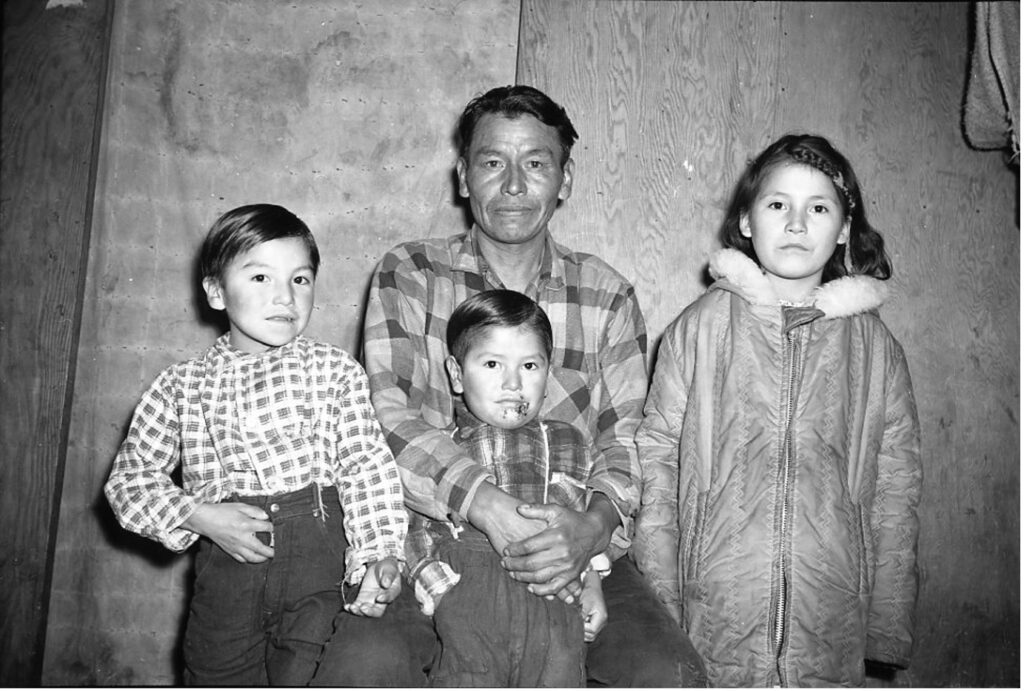

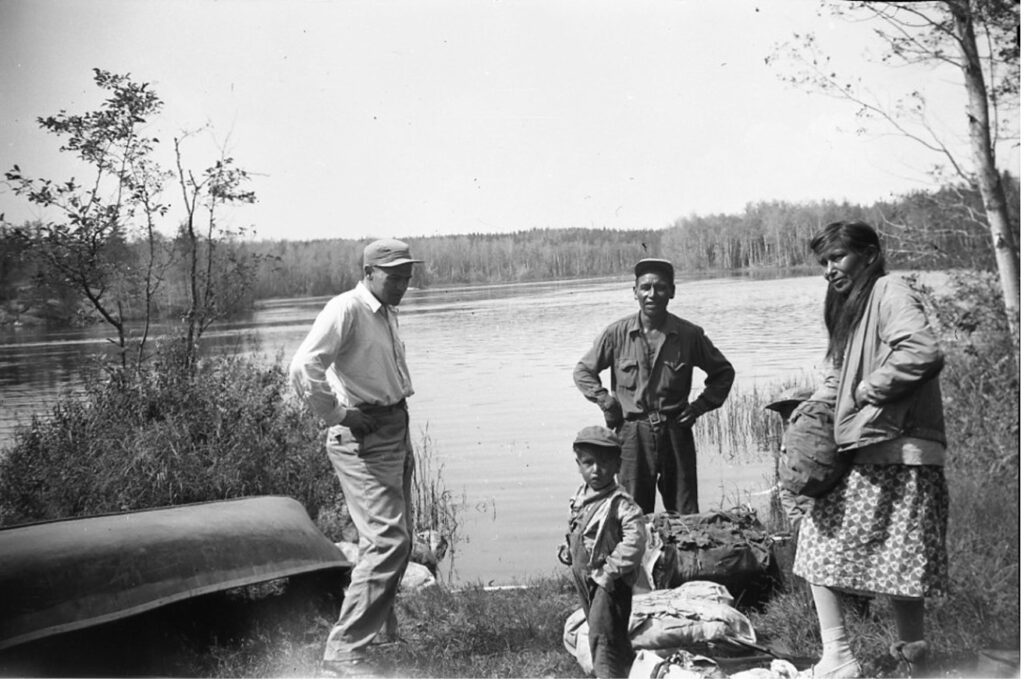

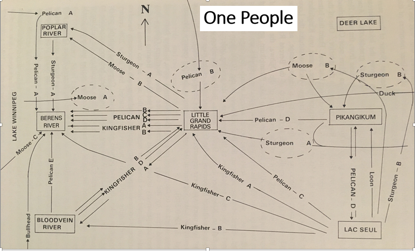

For the first time, people in Bloodvein River and Little Grand Rapids can check online to find out what the air quality is like in their communities, in real time. Guardians installed PurpleAir sensors to help residents make decisions about their health, such as when to stay indoors to avoid breathing in harmful wildfire smoke and other airborne pollutants. At 3:20pm today, the reading was 1 in Bloodvein River and 3 in Little Grand Rapids. The lower the number, the better the air quality.

Thanks to the First Nations Guardians, Pimachiowin Aki has filled a gap in Canada’s air quality monitoring system and joined a network of sensors set up all over the world!

To see current air quality readings for Bloodvein River and Little Grand Rapids, go to PurpleAir.com and search your location on the real-time map.

Wildfire Maps

You can also check out interactive maps for details on wildfires burning in Manitoba and Ontario. The maps provide information about specific wildfires, including:

- Locations

- Causes

- Danger ratings

- Status (such as active or out, under control, or out of control)