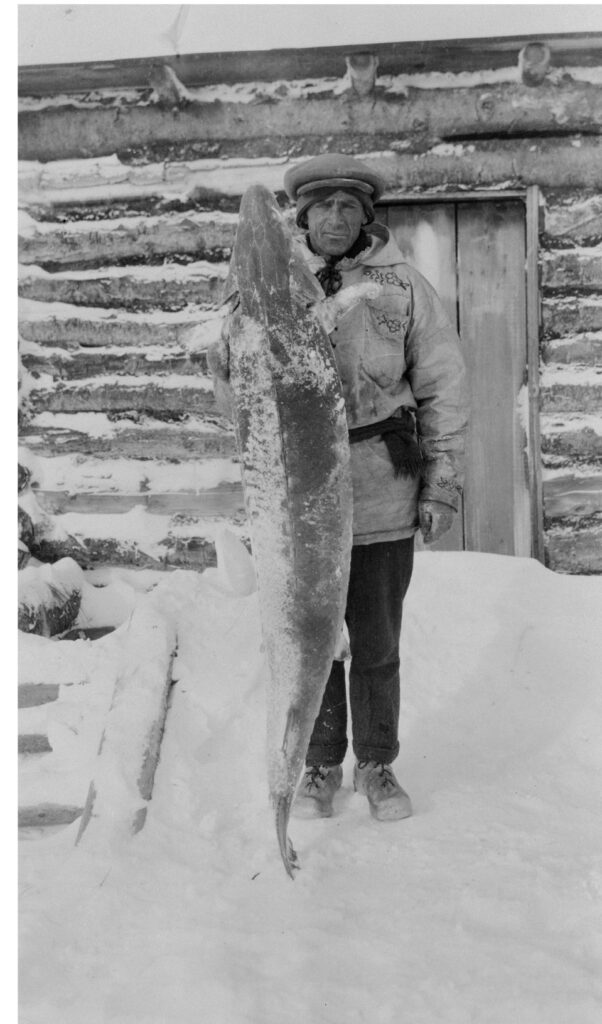

Lake sturgeon is the largest fish species in Pimachiowin Aki. An adult sturgeon can be 2.5 metres long and weigh up to 140 kilograms. Their ancestors date back millions of years.

Lake Sturgeon: Species of Conservation Concern

Today, this prehistoric giant is endangered. You can help protect lake sturgeon by recognizing its appearance and releasing it upon catch.

Who can legally fish lake sturgeon?

Only First Nations can harvest lake sturgeon in Manitoba. Lake sturgeon are protected in Manitoba and Ontario—both provinces ban sport and commercial fishing. Sport fishing is strictly catch and release.

In Canada, consult provincial and territorial websites to find out where lake sturgeon is protected by law. In addition, consult your local anglers’ guide for current sport fishing regulations.

How to identify lake sturgeon

The appearance of this evolutionary ancient fish has remained relatively unchanged for 200 million years. Here’s what to look for:

Adult lake sturgeon

- Lake sturgeon vary in colour. Adults tend to appear olive-brown or slate grey with a white belly

- Lake sturgeon have a row of bony plates known as “scutes” on their sides and back

Young lake sturgeon

- Young lake sturgeon often have black blotches on their sides, back, and snout to help them camouflage with the lake or river bottom

Would you recognize a lake sturgeon if you caught one? Here is more identifying information.

Do lake sturgeon have teeth?

No, lake sturgeon have no teeth. They have barbels that dangle by the mouth. The barbels look like teeth but, in fact, are tube-like whiskers that help lake sturgeon detect bottom-dwelling prey such as snails, mussels, clams, crayfish, insect larvae and fish eggs.

Identifying lake sturgeon by location

Lake sturgeon are found in rivers and lakes ranging from Alberta to the St. Lawrence River in Quebec, and from the southern Hudson Bay region to lower Mississippi and Alabama. While lake sturgeon prefer to spawn in fast-flowing water, they are more commonly found in murky water where they bottom feed.

Identifying lake sturgeon by behaviour

Lake sturgeon have unique behaviours. The behaviours may be feeding strategies or just playfulness:

Tail walking

Lake sturgeon are known to stand above water on their tails and move backwards, especially in warmer weather.

Jumping

You may see lake sturgeon jump out of the water and twirl around like a dolphin.

Swimming upside down

Lake sturgeon have been seen swimming mouth up, on their backs, possibly to feed on insects on the surface of the water.

Are all lake sturgeon populations endangered?

The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) designates the following lake sturgeon populations at risk:

| Population | Range | Status | Definition |

| Western Hudson Bay | Saskatchewan, Manitoba | Endangered | Lives in the wild but faces imminent extinction or local extinction (extirpation) |

| Saskatchewan-Nelson River | Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario | Endangered | |

| Great Lakes – Upper St. Lawrence | Ontario, Quebec | Threatened | Lives in the wild and is likely to become endangered if steps are not taken to address the factors that threaten the species |

| Southern Hudson Bay – James Bay | Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec | Special concern | Lives in the wild and may become threatened or endangered due to a combination of biological characteristics and identified threats |

Why are lake sturgeon endangered?

Several conservation issues have threatened lake sturgeon over the years:

1. Over fishing

Lake sturgeon reproduce only once every four to six years, so it takes them a long time to increase in population. If people are overfishing, sturgeon can’t keep up. This is exactly what happened, starting in the mid 1800s.

Mid 1800s

Caviar’s popularity was soaring. There was intense commercial fishing for female lake sturgeon and their eggs. Commercial fishers used nets to catch lake sturgeon as they swam toward spawning grounds.

Late 1800s

A lucrative commercial lake sturgeon fishery on Lake Winnipeg was developed under non-Indigenous control and largely for export to Europe. In the early days of this fishery, lake sturgeon was sold for its oil, not its meat. Lake sturgeon harvests were substantial. By 1891, overfishing became a serious threat to the species.

Early 1900s

Commercial fishing of lake sturgeon peaked. Over 445 tonnes of lake sturgeon were harvested in Lake Winnipeg, devastating the population.

1930s and 1940s

As lake sturgeon populations declined in Lake Winnipeg, non-Indigenous commercial harvesting began to take place in parts of Pimachiowin Aki. Commercial harvesting of lake sturgeon was largely unregulated. It took place mainly in spring, during spawning time. This had a significant impact on lake sturgeon populations. The species was unable to withstand the level of harvesting being done.

2. Loss of habitat

Migratory fish like lake sturgeon depend on the whole river, travelling long lengths of free-flowing water to reach shallow areas where they spawn. Climate change, poor water quality and construction of dams have all contributed to loss of habitat for lake sturgeon.

Dams and other manmade obstructions on rivers disrupt water flow and can slow or block access to spawning areas—lake sturgeon are strong swimmers but dams can cause currents that make it difficult for them and other fish to swim upstream. Dams can also contribute to changes in water temperature which affect reproductive success of lake sturgeon.

Climate change causes rising water temperatures, which in turn, decrease the quantity and quality of spawning areas.

How does Pimachiowin Aki protect lake sturgeon?

Pimachiowin Aki follows customary stewardship practices and Manitoba and Ontario laws. In addition to limited fishing, Pimachiowin Aki protects lake sturgeon by protecting its habitat from industrial development.

Pimachiowin Aki is a place where lake sturgeon can hide from predators, find food, grow to maturity, mate and spawn, and thrive. Food is plentiful, and waters are clean.

Plus, Pimachiowin Aki has many undammed and free-flowing riffle and rapid habitats, which are critical spawning areas for lake sturgeon.

Every plant and animal is a gift from the Creator and plays an important role in the ecosystem. In Pimachiowin Aki, we are monitoring the condition of habitat for species at risk, such as lake sturgeon. Lake sturgeon habitat is an important indicator of ecosystem health in Pimachiowin Aki.

Cultural significance of lake sturgeon

When we protect lake sturgeon, we are also protecting cultural heritage. Lake sturgeon provided a great source of protein for Indigenous families. A single sturgeon yielded twelve times more meat than most fish species.

Indigenous peoples cleverly used every part of the fish:

| Parts of lake sturgeon | Use |

| Meat | Food source – cooked or preserved (dried on racks, cured by the sun or smoked) |

| Back bone | Used to make soup |

| Inner membrane of the swim bladder | Used as glue |

| Bones and cartilage | Shaped into needles |

| Tail bones | Shaped into spearheads and arrows |

| Oil | Burned in lamps, used to soften homespun wool, mixed with red ochre to create paint used for pictographs |

Sturgeon is also an important clan emblem in Pimachiowin Aki. In Ojibwe, the Sturgeon Clan and its totem are called Name (pronounced Nah-MAY).

How Name Inawemaaganag, the Sturgeon Clan, came to be

A long time ago there was a couple. They were destitute. They had nothing but a baby boy. The couple was too hungry and weak to hunt. They decided to put their baby on a tree on the shoreline, hoping that someone would see the baby and help them. The couple changed into sturgeon. A group of people passed by and took the baby to raise as their own. Years later the child liked to play on the shoreline, near the water. One day he was sad and crying. Two big fish swam up to him. He knew they were his parents. Later in a shaking tent ceremony, the child learned that they were indeed his parents. This is how the Sturgeon Clan came to be.

Fast Facts

- Lake sturgeon are the largest fish in Pimachiowin Aki

- Lake sturgeon never stop growing

- Lake sturgeon are descendants of a prehistoric fish from the Upper Cretaceous Period over 100 million years ago

- While lake sturgeon can yield anywhere from 100,000 to 1,000,000 eggs every time they mate, they only reproduce once every 4 to 6 years

- Females take up to 25 years before they reach maturity. Males cannot reproduce until they are 15 years old

- Lake sturgeon are omnivores—they eat both plants and animals

- Lake sturgeon is the only strictly freshwater species of sturgeon found in Canadian waters

Feature Image: Manitoba Archives (Leach Bro. Frederic Collection)

Follow us for more information about Pimachiowin Aki:

Sources

https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/species-risk-public-registry.html

https://www.hydro.mb.ca/environment/wildlife_stewardship/fish/sturgeon/

https://www.ontario.ca/page/lake-sturgeon-species-risk

https://naturecanada.ca/news/sp-spot-lake-sturgeon/

More Fast Facts

More Fast Facts