If Anishinaabemowin is your first language as a baby and for the rest of your life, you will be Anishinaabe always and will be connected through the language.

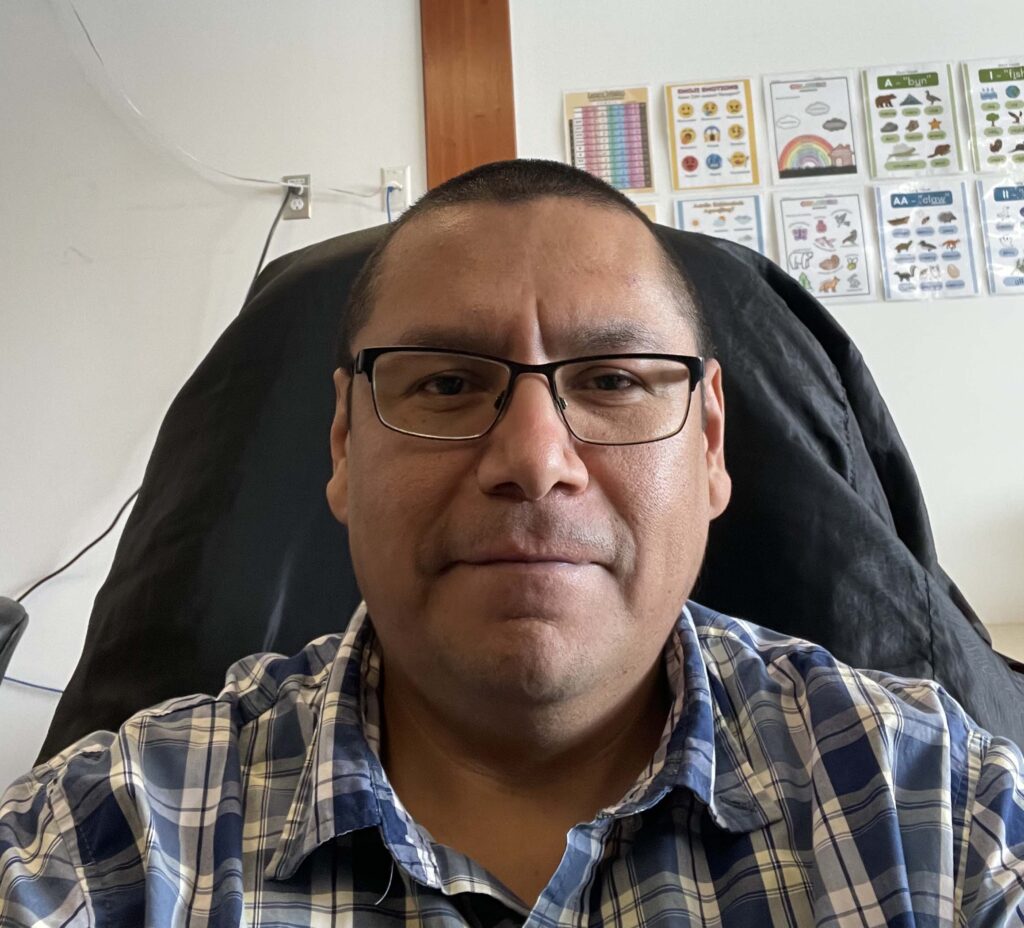

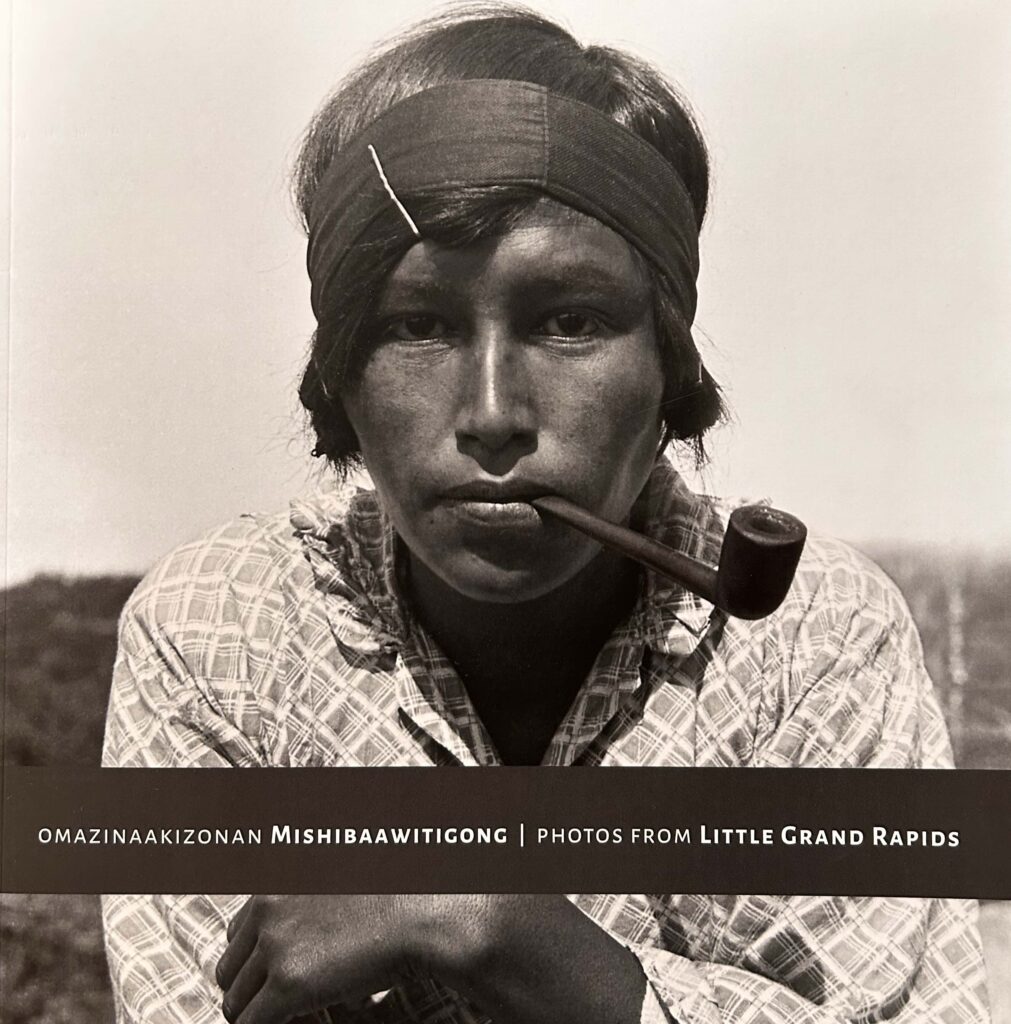

For translator Carol Beaulieu, language carries a deep responsibility. Guided by the teachings she grew up with and the legacy of the late Roger Roulette, she translated Pimachiowin Aki’s Statement of Outstanding Universal Value in Anishinaabemowin. In this Q&A, Carol shares her process, the challenges and choices behind the words, and her work to preserve Anishinaabemowin for future generations

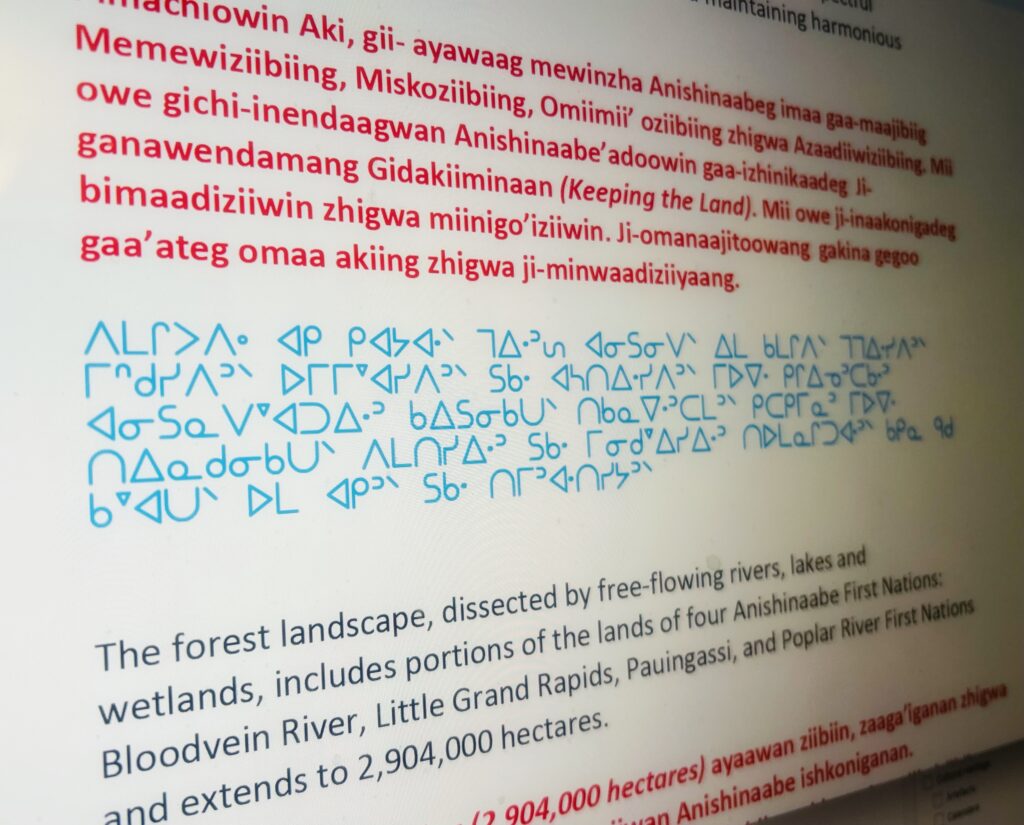

1. You translated Pimachiowin Aki’s Statement of Outstanding Universal Value (OUV) in Roman Orthograhy and Syllabics. Can you walk us through your translation process? Where did you begin, and how did you ensure accuracy and cultural integrity?

First of all, thank you for trusting me with this translation. I read the content numerous times and researched translations by the late Roger Roulette. We were close friends for many years. He was an expert in translation, transcription, reading, writing, and the linguistics of Anishinaabemowin. I wish I had taken the time to be directly mentored by him, but I did pick up things along the way which helped me complete the translation.

This is the way I try to do it. I read the English a number of times so that I understand the message clearly because I understand one does not translate directly (word for word) but contextually. In this particular translation, I had translations that Roger had done as part of the Pimachiowin Aki project. Part of translating is to not re-invent the wheel but take what already exists and edit it for your translation. Since Anishinaabemowin is my first language and I had both parents and other family members in my life until I was 14 years old, I also believe that I think as an Anishinaabe person. We were not allowed to speak English at home.

If I am not sure about a word or context, I used to ask Roger and/or my brother but unfortunately, they are both gone so I have formed relationships with other speakers, and that has been helpful.

I think as an Anishinaabe person. We were not allowed to speak English at home.

2. When you first read the OUV statement, what stood out to you about how Pimachiowin Aki is described?

My initial thought was that it was long-winded and repetitive. I realize that is how English usually is and moved past that. I find English focuses on being verbose and not getting to the point.

I want Anishinaabemowin to survive for as long as possible.

3. Describe any challenges you encountered. How did you overcome them?

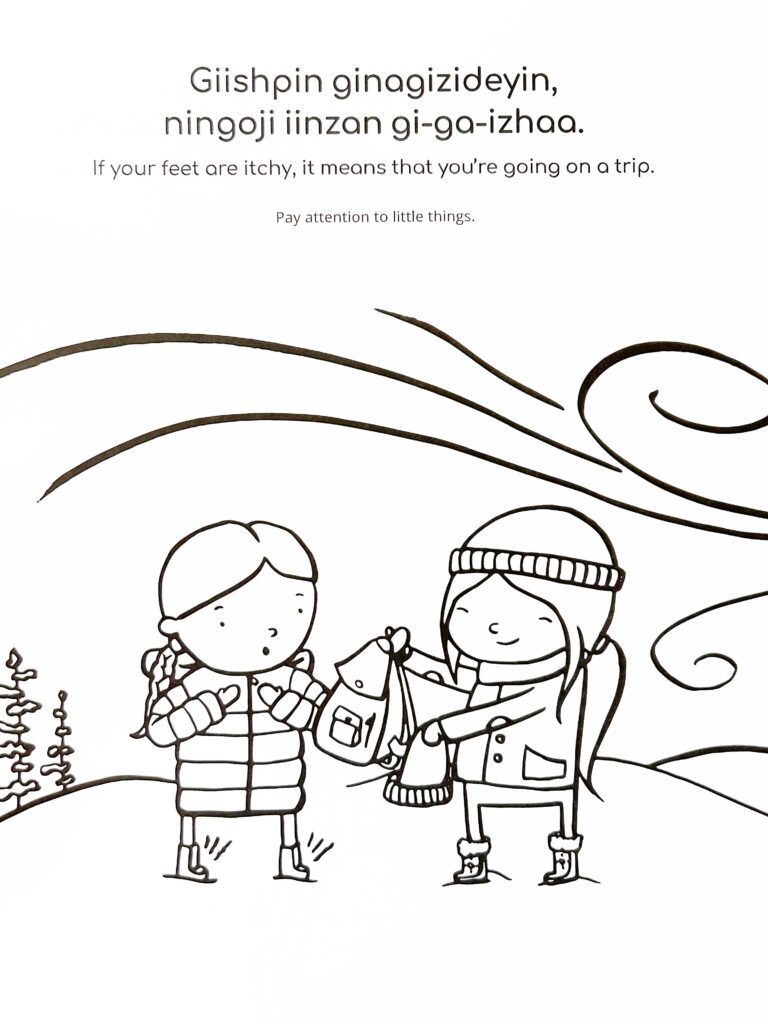

In Anishinaabemowin the context is very important and this can be challenging when translating from English. Time needs to be taken to make sure you understand what context is being portrayed. You can not usually translate word for word; it would not make sense in Anishinaabemowin.

4. Can you provide a specific example of an idiomatic expression or a culturally-specific term that doesn’t have a direct translation, and how you handled it?

The sentence below gives advice and alludes to creating more tourism opportunities. This is an on-going example of the assumptions of “settlers” when it comes to Indigenous perspectives and ideology. The monetary value always creeps in as the most viable.

The management plan could be made more proactive and strengthened to address socio-economic issues by promoting diversification and support for local economies, and through the development of action plans for specific aspects such as visitor management, to ensure it is sustainable in terms of the landscape and its spiritual associations, is under the control of the communities, and offers benefits to them.

5. Do you think the World Heritage system is compatible with Gikendaasowin (Indigenous ways of knowing/worldviews)?

For now, it appears to be, but there is no guarantee for this compatibility in the future from everyone’s perspective.

Since Anishinaabemowin is a verb-based language, one needs to understand what the nouns are trying to do.

6. How do you stay updated with language changes, new terminology, and evolving trends?

Researching, reading, going to conferences and being involved with creating new terminology.

7. How did your upbringing and the teachings you carry influence the way you approached this translation?

I have always been grateful that my parents chose to live off reserve. My father was franchised when he was a young man, so he made his own living. In the home, we were encouraged not to use English and since I was the baby of the family, my parents spoke Anishinaabemowin all the time as well as my older siblings and close family relatives. I do not consider myself an expert translator by any means, but I do my best to capture and convey the essence of what is being said so that it is understood by as many people as possible.

8. How do you ensure that cultural nuances, as well as the meaning and tone of a message, are preserved in your translations?

I think this speaks to thinking in Anishinaabemowin first and then conveying it. In my understanding, if Anishinaabemowin is your first language as a baby and for the rest of your life, you will be Anishinaabe always and will be connected through the language. I believe this because when I went to public school and a concept came up and if I had problems grasping it, I had another way of comprehending and I was able to figure it out on my own.

Language is to be shared and discussed.

9. How do you prepare for a translation project, particularly if the subject matter is new or unfamiliar to you?

I read the whole English article as many times as I need. Since Anishinaabemowin is a verb-based language, one needs to understand what the “nouns” are trying to do. From there it should start to flow.

10. How do you handle situations where you don’t fully understand something that was said? Would you ask for clarification, or try to interpret the general meaning?

I would ask for clarification from a speaker or speakers if I was stuck.

11. In your opinion, how important is building a personal rapport with the people you are translating for, and what steps do you take to foster trust?

It is important to know what they think and that you aren’t doing this alone. Language is to be shared and discussed. There needs to be open dialogue so that everyone is comfortable with the translation.

12. Pimachiowin Aki is a World Heritage site on the basis of UNESCO’s cultural and natural criteria. Which aspect did you feel most connected to as you translated it, and why?

I was so humbled to be a small part of this fantastic endeavor accomplished by Pimachiowin Aki, the First Nation communities, and all the individuals involved in this World Heritage site. I felt most connected and proud of the individuals and communities who were part of this achievement. They need to be celebrated and honoured for many years to come.

I was also grateful for the translations that the late Roger Roulette left behind. His legacy continues even though he is gone.

13. As a knowledge carrier, mother, and grandmother, how do you see this work contributing to future generations?

I only want to be titled as an Anishinaabekwe and anything I can humbly contribute, I will. I want Anishinaabemowin to survive for as long as possible. Aapiji-miigwech.