Across Canada, industrial activity and wildfires are changing forests and habitat for boreal woodland caribou. Pimachiowin Aki’s large stretch of intact boreal forest offers a rare haven for this majestic species—four groups of boreal woodland caribou live in the protected area, including one of Manitoba’s largest groups.

How Pimachiowin Aki meets the needs of boreal woodland caribou

Caribou Biologist Dennis Brannen, Wildlife, Fisheries and Resource Enforcement Branch of Manitoba Agriculture and Resource Development, explains that boreal woodland caribou thrive in Pimachiowin Aki, in part, because the vast landscape allows them to avoid predators. Boreal woodland caribou inhabit Pimachiowin Aki’s remote islands, peat bogs, and mature forest, which are typically not desirable for predators like wolves and species wolves prey upon, such as moose.

“Caribou exist in older mature forested areas where there is limited food types. Wolves have less reason to go into those areas because there’s less to feed them,” explains Dennis. Caribou are able to travel more easily in Pimachiowin Aki’s deep, persistent snow and wet peat bogs compared to wolves, he adds.

The human–predator domino effect, explained

Predators are not the root threat to Canada’s populations of boreal woodland caribou. “The general decline that we are seeing essentially comes back to human-caused landscape change,” says Dennis. Pimachiowin Aki has limited roadways and is protected from commercial mining, logging and peat extraction. In contrast, human activity across the country “has pushed the [caribou] population to the edges and restricted them to broken up patches of forests,” says Dennis.

When forest is broken into segments, it creates multiple issues for boreal woodland caribou. Dennis explains the domino effect.

“When forests are disturbed through human activity or natural causes like wildfire, regrowth is initially dominated by leafy shrubs, herbs and grasses—that new generation of vegetation is a surplus of food that leads to more primary prey species for wolves, such as moose.” Wolves follow and ultimately prey upon caribou, too.

Developments such as roads and trails also pose a threat. Dennis describes these linear features as “highways for predators.” They allow wolves to get into areas that were once less accessible, pick up speed, and prey on boreal woodland caribou.

Wolves are not caribou’s only predators. Other species will prey on them “when an opportunity presents itself,” says Dennis. “Across the boreal forest, black bears will prey on boreal woodland caribou calves. Out west in the Rocky Mountains, cougars prey on caribou, especially younger caribou,” he adds.

The climate change-predator domino effect, explained

Boreal woodland caribou travel well in wetlands. “When you bring climate change into the scenario, those wetlands become dryer,” says Dennis. In dryer times, wolves can get into those areas more efficiently. “This has implications for predation on caribou as well.”

Caribou birth rates

Another factor contributing to Canada’s declining boreal woodland caribou populations is that caribou don’t have as many young as other wildlife.

“Moose, elk and deer often have twins,” says Dennis, noting that this is rare in the caribou world. “Caribou will only have one offspring per year, so you end up in a situation where more [caribou] are being removed than added to the population in many cases.”

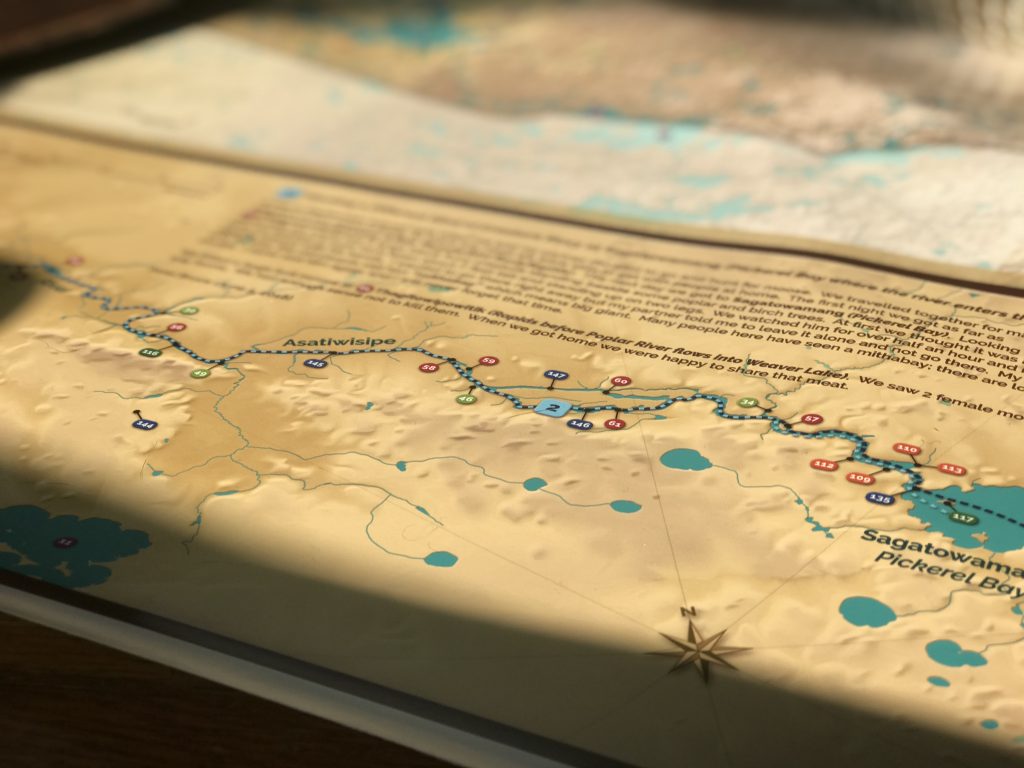

Ghosts of the forest—Caribou sightings in Pimachiowin Aki

Pimachiowin Aki Guardian Dennis Keeper reports seeing few caribou in Little Grand Rapids First Nation. “Fifteen to 20 years ago, we used to see hundreds and hundreds of them while traveling winter roads.” That is no longer the case. “I saw 14 of them two springs ago—a group of females. You don’t even see tracks now.”

Dennis Brannen suspects that caribou have started to avoid busier areas, like the winter roads. “Caribou are known as shadows or ghosts of the forest. They’re a secretive animal, so they don’t always show themselves when they’re around that landscape. They just shy away from where people are.”

Living with wildfire in Pimachiowin Aki

“Caribou have learned to live with fire [in Pimachiowin Aki] through time,” says Dennis Brannen. Fire is an opportunity for land to renew itself and create new and future habitats. “It’s only when we start increasing the amount of human disturbance on the landscape in combination with fire that we start seeing negative impacts on caribou populations,” he says.

But climate change could change that, warns Dennis. “With climate change, we potentially see an impact with the size of fires and frequency and intensity of those fires on landscapes. So, there are likely to be negative impacts to available habitat and population through time.”

The future of boreal woodland caribou

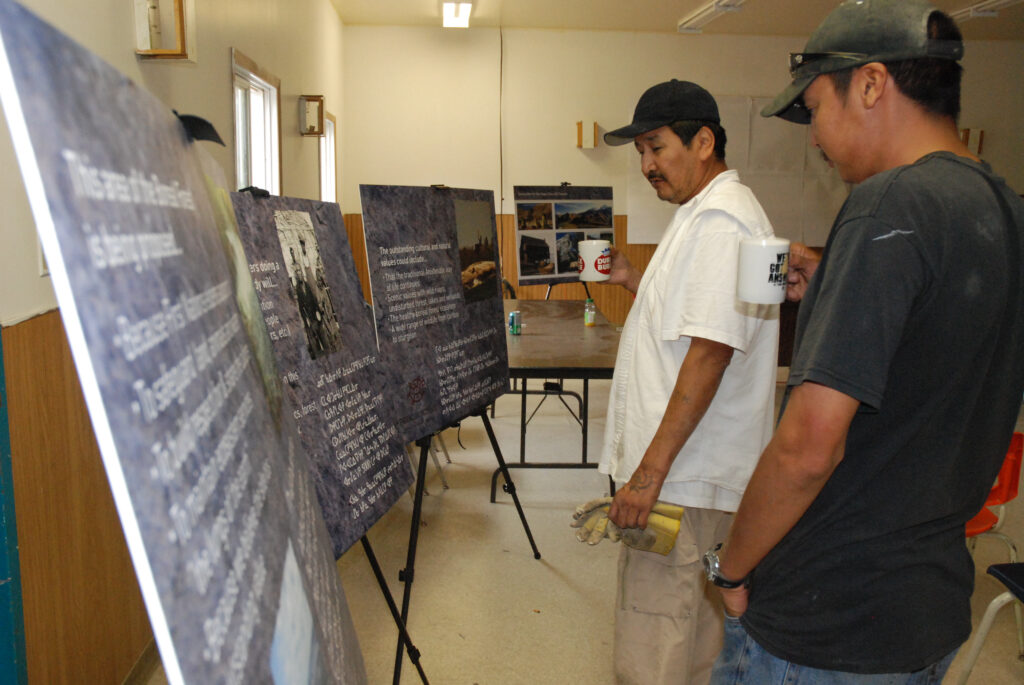

Across Canada, people are combining western and Indigenous ways of knowing to protect boreal woodland caribou and their habitat.

“Our desire is to do a better job as we move forward to bring Indigenous knowledge into caribou conservation here in Manitoba,” Dennis shares.

Manitoba’s boreal woodland caribou recovery strategy sets out goals that align with Canada’s recovery strategy. A key goal is to manage and protect boreal woodland caribou habitat to sustain populations across the land. However, results will not happen quickly.

It’s a long-term process and we have to keep that in mind,” says Dennis. “We can’t just say, okay, we’re protecting undisturbed landscape and expect caribou to start doing well tomorrow. We need to look at opportunities and ways in which we can move disturbed habitat back into a state that is suitable for boreal woodland caribou use in the future.”

Research from across Canada indicates that when a habitat is disturbed by industry, for example, it takes roughly 60 years for that habitat to become useful to caribou again.

“We are constantly reviewing developments and proposals, and looking at how they may or may not impact caribou directly,” says Dennis.

There is hope for boreal woodland caribou. Last year, it was reported that the George River population (Labrador and Quebec) increased for the first time in 25 years. That area banned hunting of caribou in 2013. However, woodland caribou are not protected across the country. Their survival is tightly woven into the long-term health of boreal ecosystems, such as those of Pimachiowin Aki.

Anishinaabeg continue to provide wildlife, including threatened species like boreal woodland caribou, with healthy habitat. Here caribou will continue to feed in both winter and summer months and find safe spaces to calve and raise their young.

Fast Facts > Boreal Woodland Caribou

Photos: Hidehiro Otake, Doug Gilmore

More Fast Facts

More Fast Facts