There has been much dispute about global warming and climate change but Anishinaabeg have long known that poor land use planning can have damaging results. The Elders who came before us have taught us to respect the earth. Pimachiowin Aki is a gift from the Creator, and Anishinaabeg have a sacred responsibility to care for it.

Years ago, Elders spoke about the impending changes in weather patterns and cautioned us that we must work together to make a difference for current and future generations, says Pimachiowin Aki Board Co-Chair William Young. “We have our own scientists,” he says, referring to the Elders in the communities.

William generously translates as we speak with Bloodvein First Nation Elder Leslie Orvis. Born in Bloodvein, Leslie has worked all over Manitoba as a commercial fisherman, and is an experienced hunter and trapper.

Leslie sees the changes that Elders talked about long ago. “They used to be able to do various things, like make it rain. Now that’s all changed,” he says.

While we may no longer be able to call upon the clouds to open up, the Elders in Pimachiowin Aki are the knowledge keepers. Sharing their traditional knowledge is invaluable. They talk about the effects that global warming has on the wildlife in their communities.

At the end of November, Bloodvein was experiencing rain and unusually warm weather for about a week and a half. “When it rains this time of year,” Leslie says, “it freezes onto the twigs, trees and bushes, which the moose and rabbits rely on to eat.“

Lack of food for wildlife inevitably affects the trappers and hunters.

“The wolves are starving,” William adds. Recently three wolves were spotted on the road walking at night, desperately searching or food, coming closer than normal to residents’ homes.

Communities Affected by High Waters

Dennis Keeper, a Pimachiowin Aki Guardian who observes the lands and waters in Little Grand Rapids is very concerned about the unusual weather patterns and erratic water levels that he has witnessed over the last few years.

“Usually at this time of year, the water levels drop and the current slows down,” he says. But this year is different. The lake froze once in the fall and then opened again near the end of November. Yet in June and July, water levels were lower than normal. Dennis says that in 2018 Little Grand Rapids had low water levels all year.

Pauingassi First Nation, 18 kilometres north of Little Grand Rapids, is experiencing its highest water levels ever, with some parts of the community swallowed up and becoming islands. The high waters prevent trappers from accessing their trap lines.

“We have to rely on outside food, says Dennis. “It puts pressure on the community.”

It also affects communities’ access to transportation. Typically, for about one month each winter, people use winter roads to travel to and from the communities of Pimachiowin Aki. The roads are a direct route across the lakes. But those roads won’t open until the lakes freeze, and Dennis worries that the roads won’t be open for as many days as needed.

“It takes a month of minus 30 degrees Celsius for it to freeze,” he explains. It takes six to eight weeks to get the roads passed as driveable, which results in 22 to 30 days of winter road driving. The slow freeze-up can also result in the trucks having to carry smaller loads, cutting the weight of the loads in half from 80,000 pounds to 40,000.

This is unsettling news for Little Grand Rapids, which is expecting 1500 loads of supplies this winter via the winter road. The trucks will be carrying materials to build the community’s own much-needed high school this spring.

“Global warming is not a myth,” Dennis says. “Come over here and see it for yourself.”

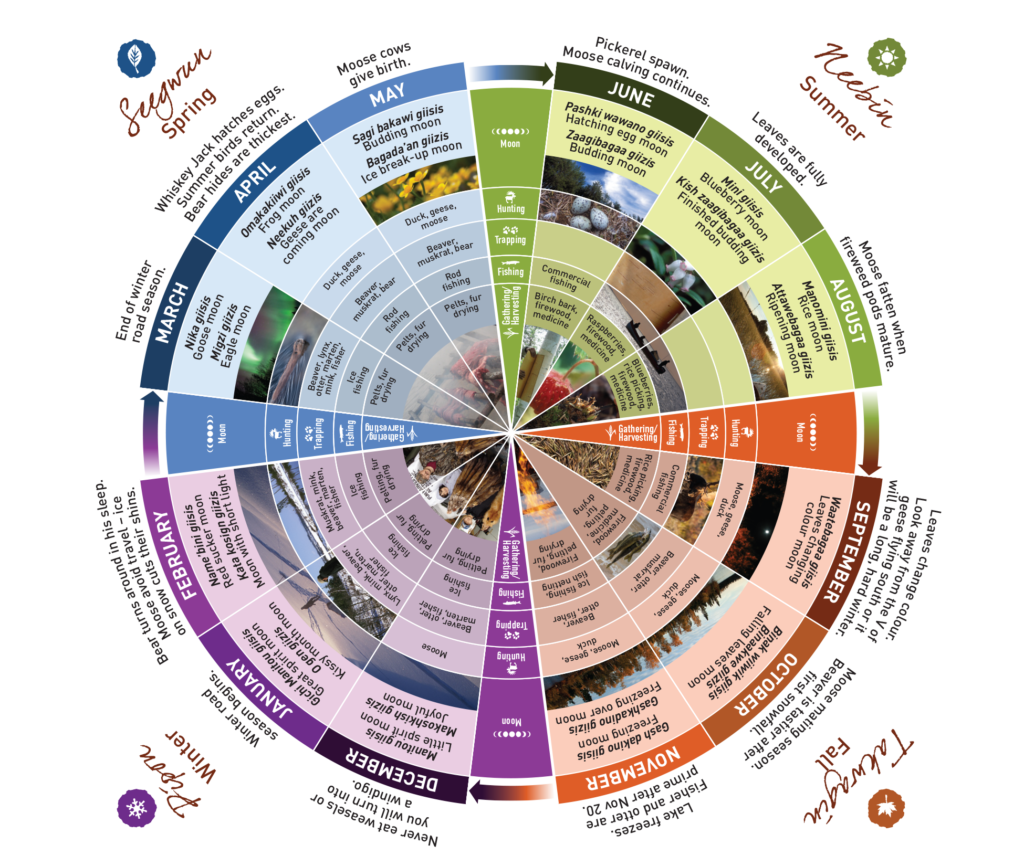

Elder Leslie says, “There will be days ahead that will be hard, and we have to prepare our youth by teaching them skills like hunting, trapping, fishing and survival.” He believes that we can, and should, all work together toward sustainable hunting in order to build a brighter future for all.