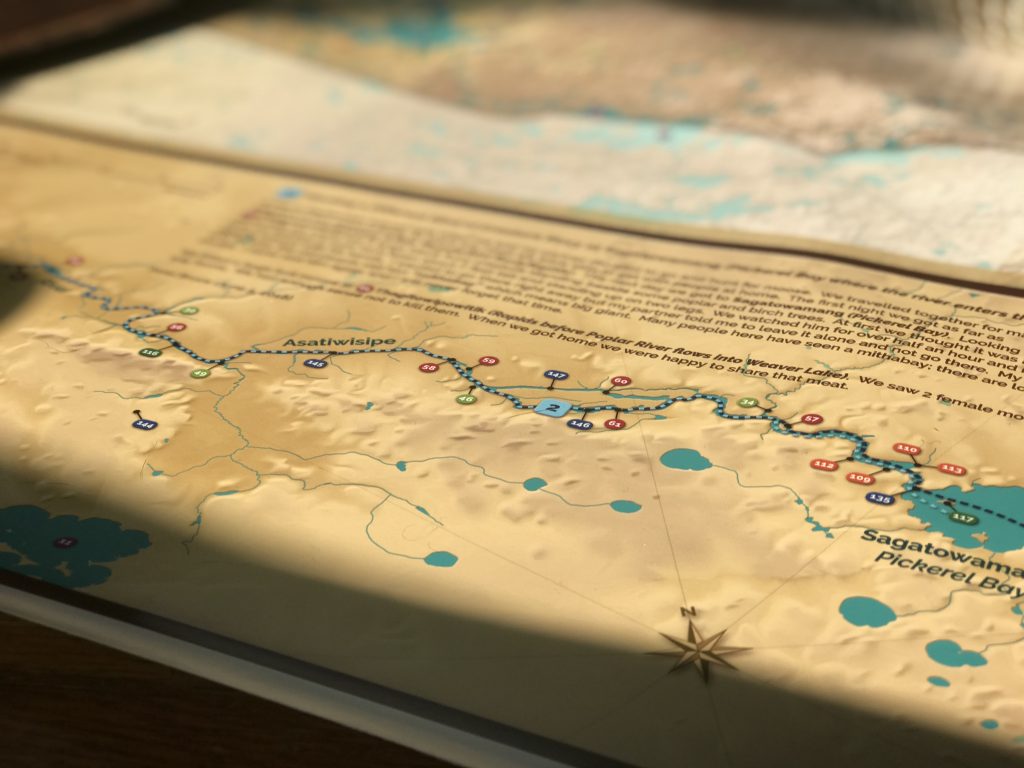

Poplar River First Nation recently completed a Traditional Place Names map, which gives meaning to 149 places. The named places include rivers, lakes, creeks, rapids, points, and islands.

For several years, Elders in Poplar River have been sharing their knowledge to make this map possible. For instance, the Elders have walked the land with us and showed us places and things that are known only because Elders have been there and shared their knowledge. The Elders’ stories and memories are now printed on a huge, colourful map that will hang in community spaces and guide our journeys. The map is almost five feet wide!

When traveling the land, Anishinaabeg tell stories about the named places we encounter along the way. When we learn the names of places, we gain an intimate knowledge of the land. We need this knowledge for survival. Some places are named after plants or wildlife found in the area. Some names warn of dangers. Many reflect the histories of people who have traveled through and made use of the land.

Named Places to Visit in Poplar River First Nation

Here are a dozen named places to visit using the Poplar River First Nation map:

- Nikaminikwaywining (The creek where geese drink)

- Pinanaywipowitik (Rapids where people can rest sore legs)

- Moozichisking (Big rock shaped like a moose’s rump)

- Wapiskapik (The rock island that was painted white so it could be seen)

- Kakinoosaysikak (Place where there are lots of minnows)

- Weeskwoywisaguygan (Marchand Lake—shaped like a balloon)

- Moondeewiminitik (Island named after the late Elder Mooni)

- Kaminotinak (Beautiful high ground along the Franklin River where small trees grow)

- Nayonanashing (Place to stop for lunch)

- Wapeegoozhesse’opimatagaywining (Where a mouse swam across the river)

- Paagitinigewening (Tobacco offering rock)

- Kakpikichiwung (Water falls over a rock cliff)

Preserving Cultural Heritage

All 149 places on the Poplar River First Nation Place Names map are now officially recognized in provincial and national geographical names databases. In addition to helping us navigate the land and waters, the map preserves our cultural heritage. In other words, the map preserves Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe language), history, teachings and beliefs.

Listening to and talking about our place names is like reading a book…these named places ensure that the stories will carry on. When my father was describing where he had been, he would say, kee’yapay namaytoowag, which means he could still feel the presence of people who had been there before. The stories of our ancestors are connected to those places and to us by the place names.

– Sophia Rabliauskas

Meegwetch to the Poplar River First Nation Elders for their generosity, time, and patience in documenting the personal and collective histories of the people who have travelled through, observed and lived on Poplar River First Nation ancestral land, Asatiwisipe Aki.

Do you want to view the full Poplar River First Nation Place Names map on our website? Click on this link and scroll down toward the bottom of the page.

More Place Name Maps for Pimachiowin Aki

Pimachiowin Aki Corporation is working to protect cultural heritage for future generations in all four First Nation communities in Pimachiowin Aki. Cultural heritage expresses who we are and how we live. It consists of everything that we value and share through generations. Cultural heritage includes place names. It also includes travel routes, cabins, songs and traditional knowledge.

We are crossing land and water to inventory Pimachiowin Aki’s cultural sites. For example, we are documenting named places, pictographs, Thunderbird nests, cabins, campsites, and ceremonial sites. Bloodvein River First Nation, Pauingassi First Nation and Little Grand Rapids First Nation are each collecting this information to make their own place names maps.

This summer, eight young adults had a one-of-a-kind experience using the Poplar River First Nation Traditional Place Names map. Read about it here:

13 Rapids with a Traditional Place Names Map in Hand