A Pimachiowin Aki Director learned years ago that an interview with Little Grand Rapids First Nation medicine man William Bones Leveque was recorded in the 1960s.

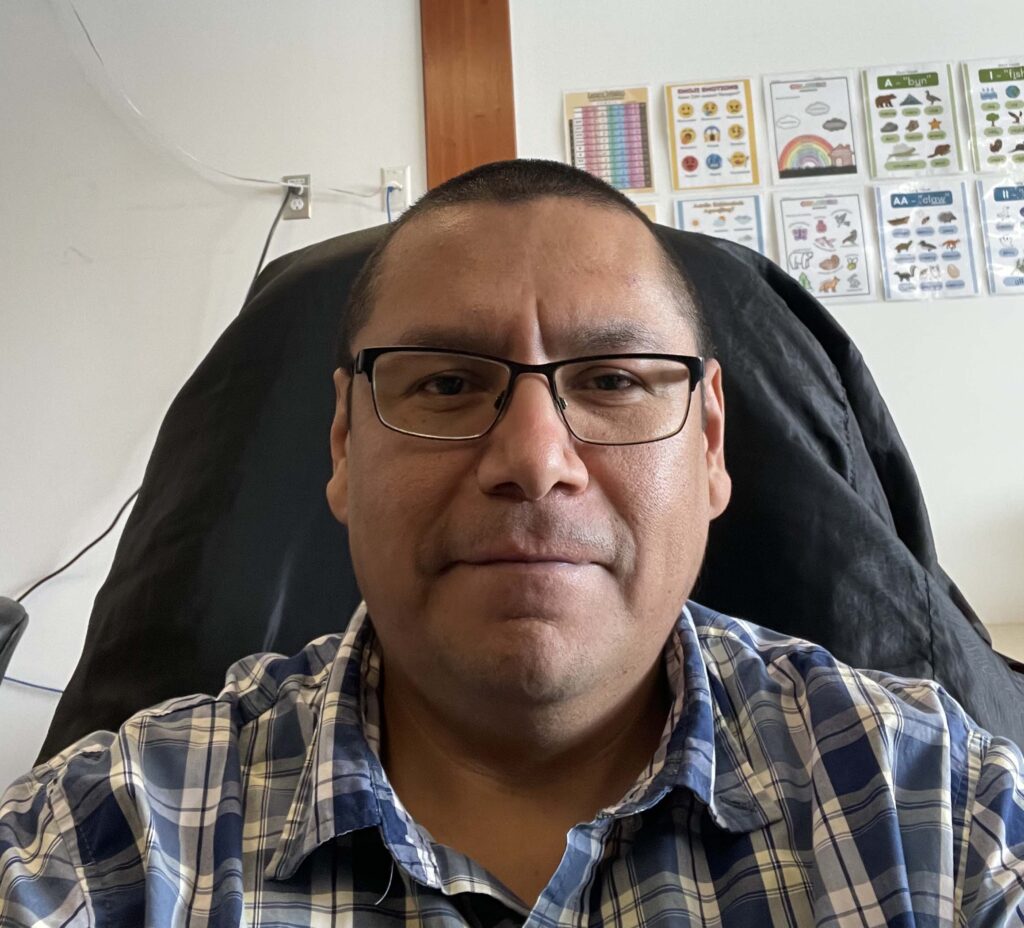

“I read about the interview in the Hudson Bay Company (HBC) records when we did a history project at school for the community,” says the Director for Little Grand Rapids First Nation.

He has wanted to hear the recordings ever since. It was his idea to find the recordings and share them with the people of Pimachiowin Aki.

The recordings (below) are part of a collection of film and sound recordings that were either created or acquired by HBC.

Learn more about the Hudson’s Bay Company film, video and sound collection

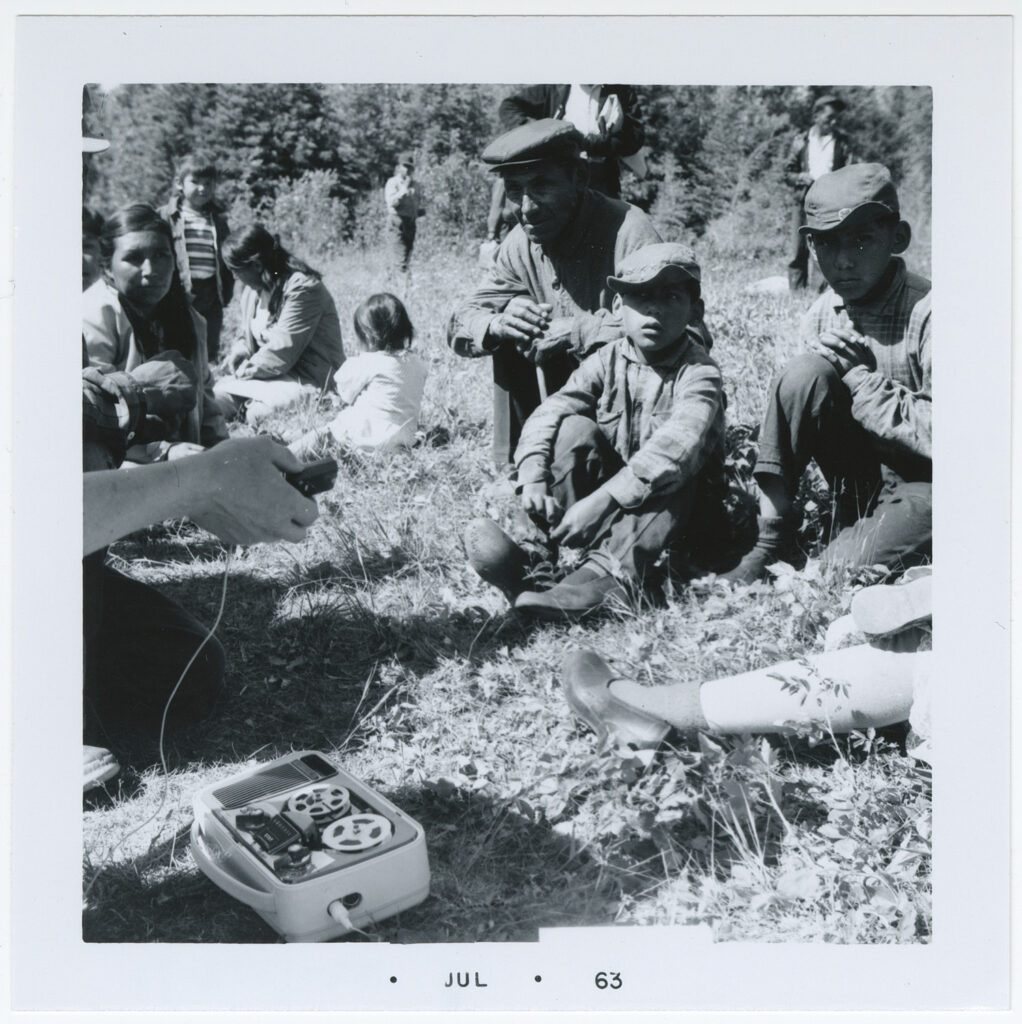

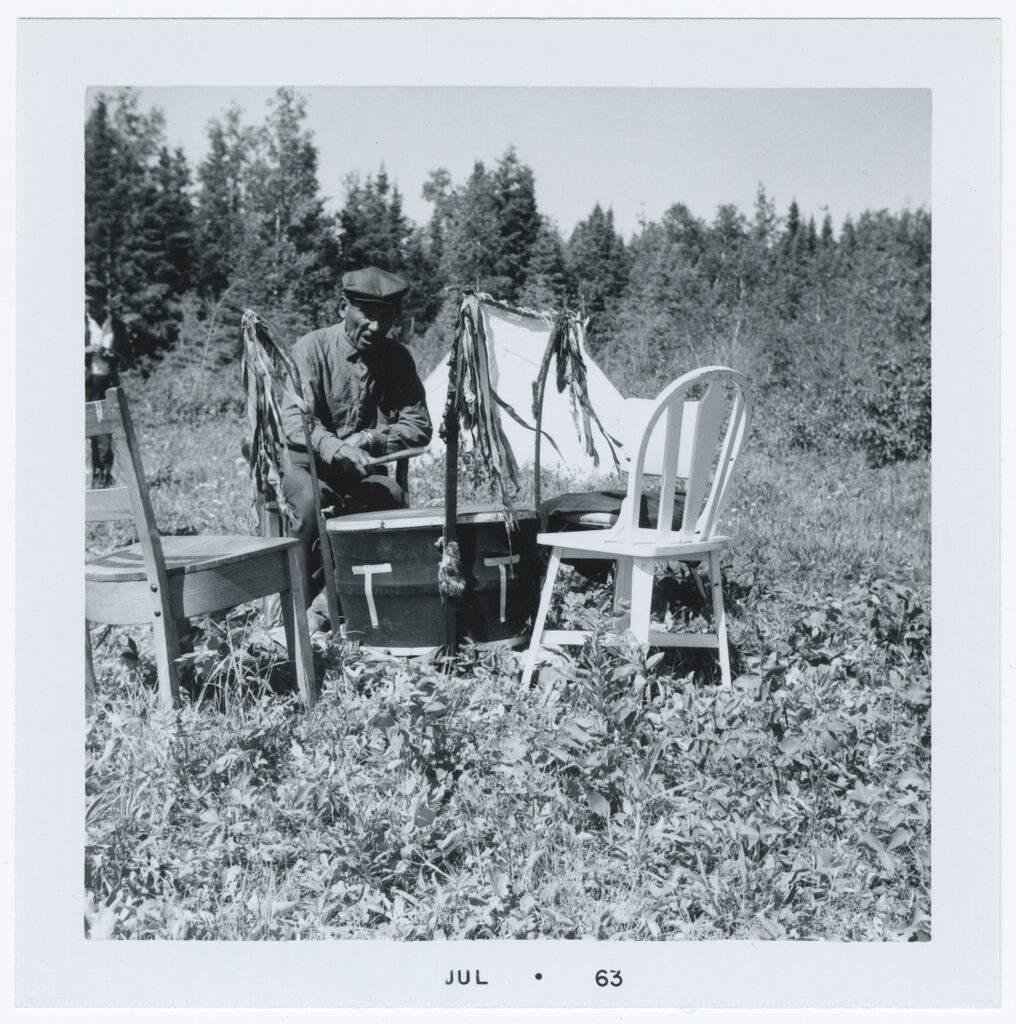

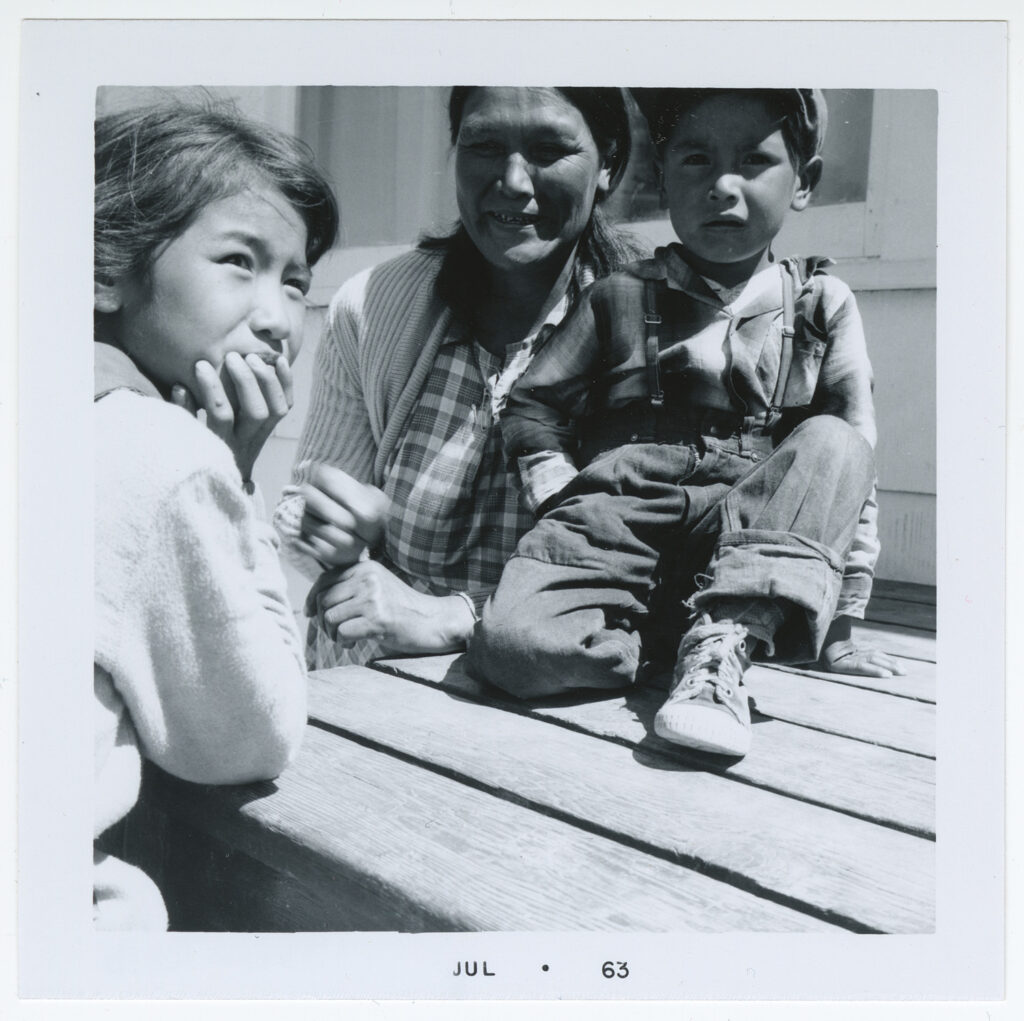

Feature Photo: William Bones Leveque answering questions for tape recorder operated by Don Ferguson

Photographer: Don Ferguson, 2 July 1963

Don Ferguson fonds, Hudson’s Bay Company Archives, Archives of Manitoba

HBCA-T7-1

Little Grand Rapids [drum dance ceremony and interviews with medicine man William Bones Levesque, interpreter David Duck and HBC employee Walter Moar], [Moccasin Telegraph, Fall/Winter 1963]

HBCA-T7-2

Part two of an oral interview with HBC employee Walter Moar. See transcript below.

HBCA-T7-2 Transcript

Transcribed to the best of our ability.

[Speaker 1] Interviewer Don Ferguson (HBC employee)

[Speaker 2] Interpreter Walter Moar (HBC employee)

[Speaker 3] Unknown

[Speaker 4] Unknown

Relocation after the store burned down

[Speaker 1] (0:00) When did they move over to the other location?

Inaudible

[Speaker 1] Why did they move over there?

[Speaker 2] Well, they figured, they see, when the store burned out here, because they had hard time to come across here, see, with the water, because the water’s always open

Click here for full transcript

[Speaker 1] I see.

[Speaker 2] (0:27) They have to go around. When they put the store out there, see, they can go in right there.

[Speaker 1] Right

[Speaker 2] Even the airplane couldn’t land here, they have to go around before they can get a mail.

[Speaker 1] I see, and that’s why they moved across.

[Speaker 2] I think that’s what they had to do.

[Speaker 1] I see. And then, um, uh, they just let these buildings go after that, didn’t they?

[Speaker 2] Yeah, yeah.

[Speaker 1] But they burned out, the store burned down, eh?

[Speaker 2] Yeah, yeah. The store burned down and then they built the other one across.

[Speaker 1] I see.

[Speaker 2] This one was… I’ve got this one. They tear it down, they leave boards.

[Speaker 1] Yeah, yeah.

[Speaker 3] Inaudible

[Speaker 2] 01:15 No, no. I think it’s the first one was used by my grandfather, Tony Moar.

[Speaker 1] This is the one that’s still left.

[Speaker 2] Yes. Tony Moar, yeah.

[Speakers] Inaudible

[Speaker 1] 01:28 But, uh, Walter says that they first established at Moar Lake. I didn’t know that. Uh, the first store, and then they came here, and then over to the present site.

[Speaker 3] Inaudible

Moving goods by canoe

[Speaker 2] 1:58 This would be after the Berens River. Well, I guess that’s what they said. They got energy from the Berens River to Moar Lake, and they hauled it in by canoe.

[Speaker 1] 2:20 Can you come from Berens River to here now without a portage?

[Speaker 2] No, no, not a portage. Without a portage is…

[Speaker 1] Fifty-two. Fifty-two…

[Speaker 2] Yeah, we used to haul it straight.

[Speaker 1] You were a boy back then.

[Speaker 2] Yeah, when I was a young boy, yeah. I used to haul it straight to the Berens River.

[Speaker 1] Oh, yeah.

[Speaker 2] 2:47 Well, before they moved, they had a tractor over here. They’d bring the stuff by the tractor to here, see?

[Speaker 3] Oh, yes.

[Speaker 2] And after that, they moved across.

[Speaker 1] I see.

[Speaker 2] That was before we used to haul it by canoe. About 1,500 pounds in each canoe.

[Speaker 1] I see.

[Speaker 2] Too many.

[Speaker 3] And you carried 90-pound packs like they used to carry all day?

[Speaker 2] 3:16 Oh, yeah. Some of them carried 400 pounds in a bag.

[Speaker 1] That’s bags of flour.

[Speaker 2] Yeah.

Inaudible

[Speaker 2] Get a few lynx, too. Beavers, birds.

Then and now

[Speaker 1] 3:42 Are the people better off now, would you say, than they were, say, 15 years, 20 years ago?

[Speaker 2] Well, first, I think they have a little bit of family allowance, but before they never had family allowance, not in 20 years ago.

[Speaker 1] They’re getting more income and everything now…

Inaudible

[Speaker 1] … and they’re better health-wise, would you say?

[Speaker 2] I think so. I think so.

[Speaker 1] 4:10 Like, with the nursing station being here?

[Speaker 2] It was a long time ago, nobody ever got sick. I never knew. And I never knew (inaudible) long time ago.

[Speaker 1] Mm-hmm. Well, that’s unusual, because there used to be a lot of people go out every Treaty time, didn’t there?

[Speaker 2] Yeah, yeah. But now…

[Speaker 3] The people they have to learn (inaudible).

Trading with Pauingassi

[Speaker 1] 4:43 What about the Pauingassi crowd? What’s happened there?

[Speaker 2] Well, you see, they belong to this Indian reserve. They belong to this reserve.

[Speaker 1] Yeah.

[Speaker 1] They stay out there, see, because they got the better fishing out there. They eat fish, see. (inaudible)

[Speaker 1] 4:54 I see. I understand they don’t like the people here.

[Speaker 2] I don’t think so. Well, I don’t know much about that… (laughs)

[Speaker 1] Well, what do they do as far as trading, Walter, is concerned?

[Speaker 2] Well, they come down here to…

[Speaker 1] Oh, I see. They would come down once a week, or once every two weeks, you tell me.

Inaudible

Commercial Fishing

[Speaker 1] Oh, I see. I see. Well, Pete Lazarenko was in here commercial fishing, wasn’t he?

[Speaker 2] Yeah, he was, he was, he was… well, in the fall; every fall, October.

[Speaker 1] Oh, I see. Late fall, eh?

[Speaker 2] Yeah, late in the fall.

[Speaker 1] 5:44 And does he take fish right in the, in Berens River, or…

[Speaker 2] Oh, yeah, they take fish in this lake, and they take fish in this fishing lake.

[Speaker 1] I see.

[Speaker 2] In this lake.

[Speaker 1] Tracy’s up there now, is he?

[Speaker 2] 5:54 Yeah, Tracy’s out there. He’s got lots of… (inaudible)

[Speaker 1] Is he getting any business, any customers up there yet?

[Speaker 2] Yeah, he’s got a few now.

[Speaker 1] He has, eh?

[Speaker 2] Yeah.

[Speaker 1] I see.

[Speaker 3] It’s quite early, too. They only opened… (inaudible)

[Speaker 2] Oh, yeah. Oh, yes.

Inaudible

[Speaker 2] Sometimes rain, cloud. They never got wet.

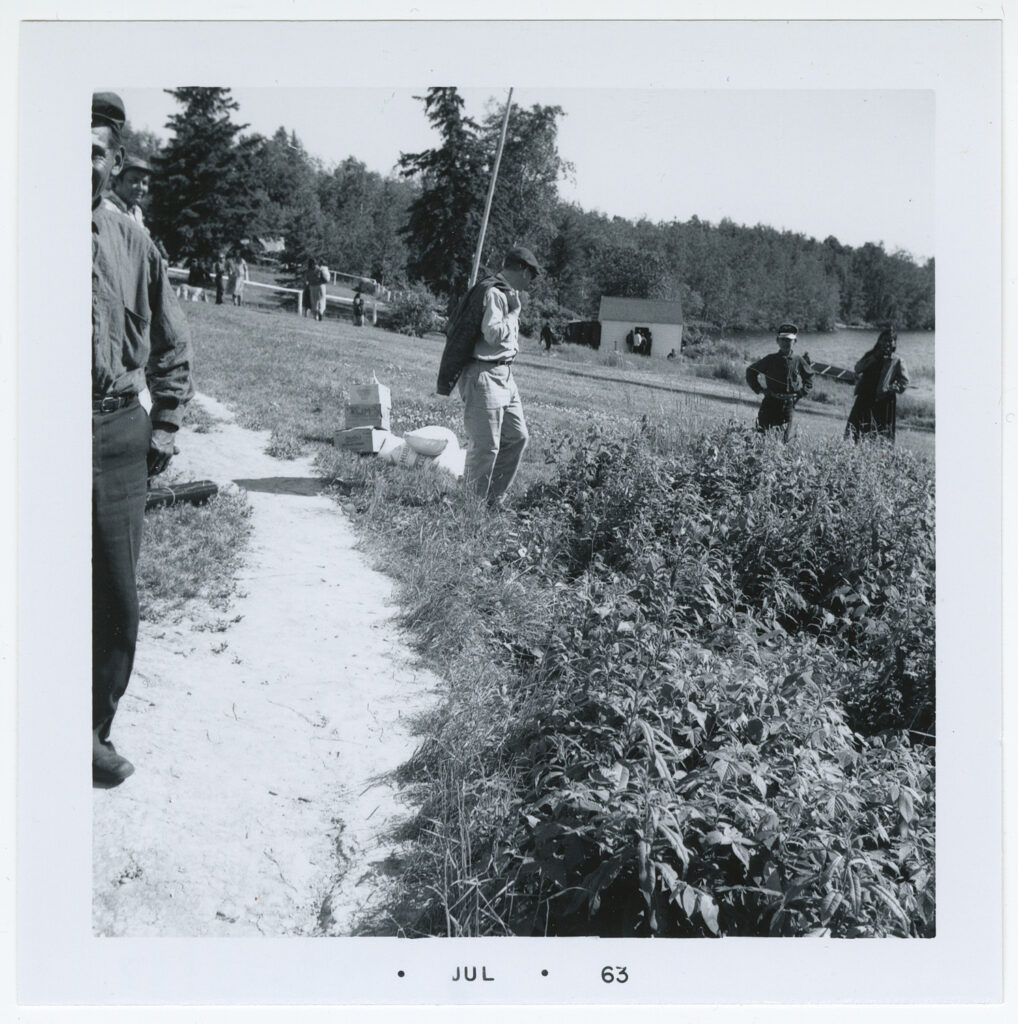

Agriculture

[Speaker 1] 6:28 Oh, I see. So they, that’s another reason why they kept, moved across, eh?

[Speaker 2] Yeah. Yeah (inaudible). Another one way out there. Gardens.That was my grandfather’s here. Potatoes. He had lots of rhubarb.

[Speaker 1] Rhubarb.

[Speaker 2] Oh, yeah. Everything, they had here.

[Speaker 1] Oh, yeah.

[Speaker 2] They had two horses here.

Inaudible

[Speaker 3] 7:04 Well, they usually have many horses in this part of the country, right?

[Speaker 2] And since when we went out to Berens River, no more horses.

[Speaker 1] No.

Inaudible

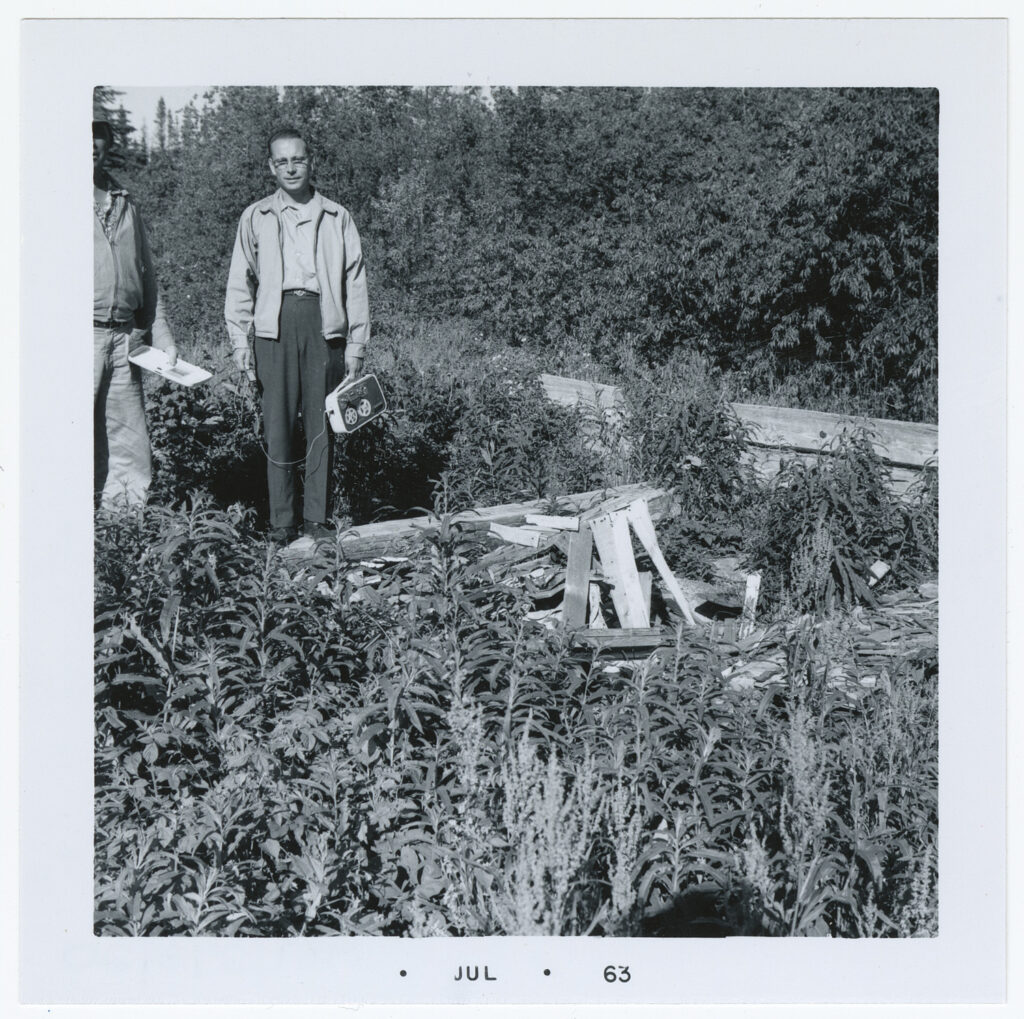

Waste Disposal Practices

[Speaker 1] This is still the, the path, like, that they used to come up on, eh? And they hump the flour on their back coming up here. Walter, do you know where the garbage dump was, where they threw the garbage and that?

[Speaker 2] Oh, it was way up in the bank there.

[Speaker 1] I see. Doctor, uh, Walter was saying that their refuse disposal was way behind the house there. That might have been an interesting spot to look into.

[Speaker 2] Oh, yeah. Well, everything, they must have… they bury everything. See, they dig down the hole and they throw everything in there.

[Speaker 1] Is that, that was how they used it, eh? They buried all the garbage?

[Speaker 2] They buried out all that stuff in their cans and all that stuff.

Trading a Double Barrel for a Single Barrel

[Speaker 4] 08:13 Warden Crone, the manager, was at Pukatawagan.

[Speaker 1] Oh, yeah.

[Speaker 4] And he got it from, eh, in Dillon… Dillon, Saskatchewan.

[Speaker 1] 08:20 Oh, yeah.

[Speaker 4] 08:13 And I had, I got a double barrel. See, I got a double barrel in Pukatawagan and I traded him plus ten dollars for this single barrel.

[Speaker 1] Oh, I see.

[Speaker 4] But the double barrel, they sawed it off, you see. It was a sawed-off shotgun, just like it. So I wouldn’t, you know, this was in bad condition. I’ve got it at the post office.

[Speaker 1] Yeah, I’d like to have a look at it when we get back.

[Speaker 3] (inaudible)

Gallery

Photo Galleries

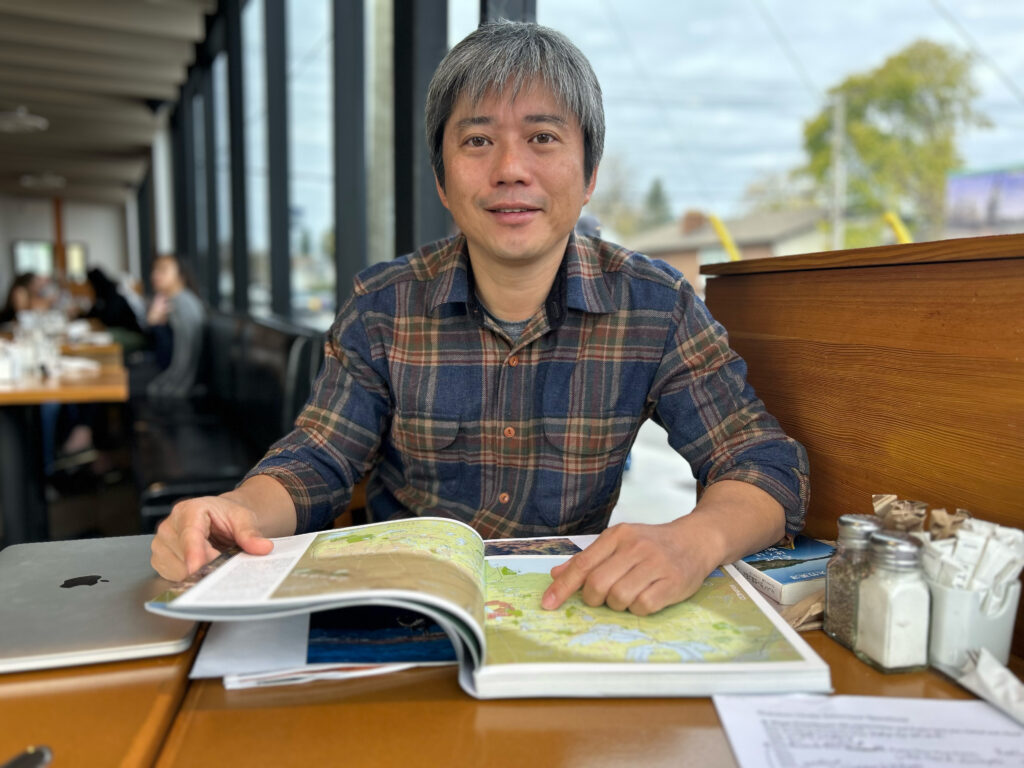

Photographer: Ōtake Hidehiro, May 2024

Keeper of the William Bones Leveque drum: Carlisle (Car Leslie) Bushie

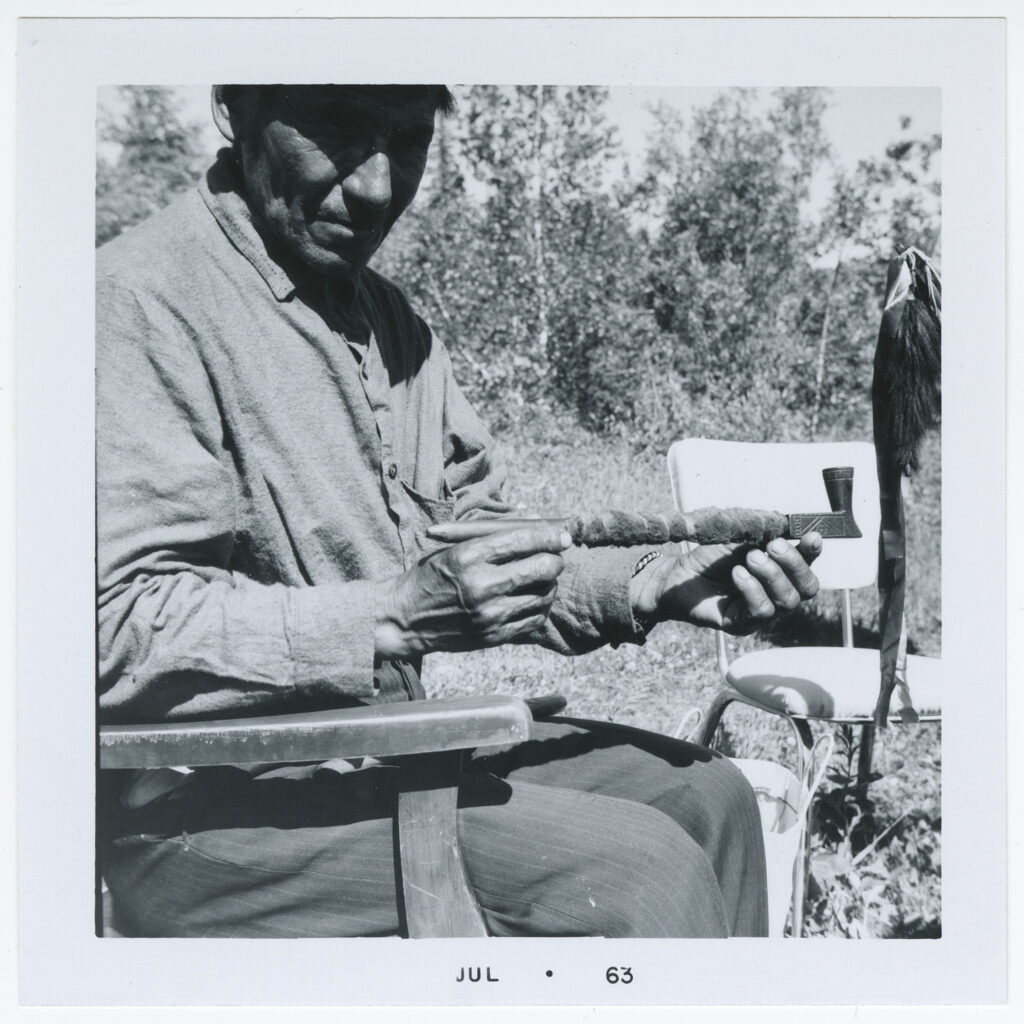

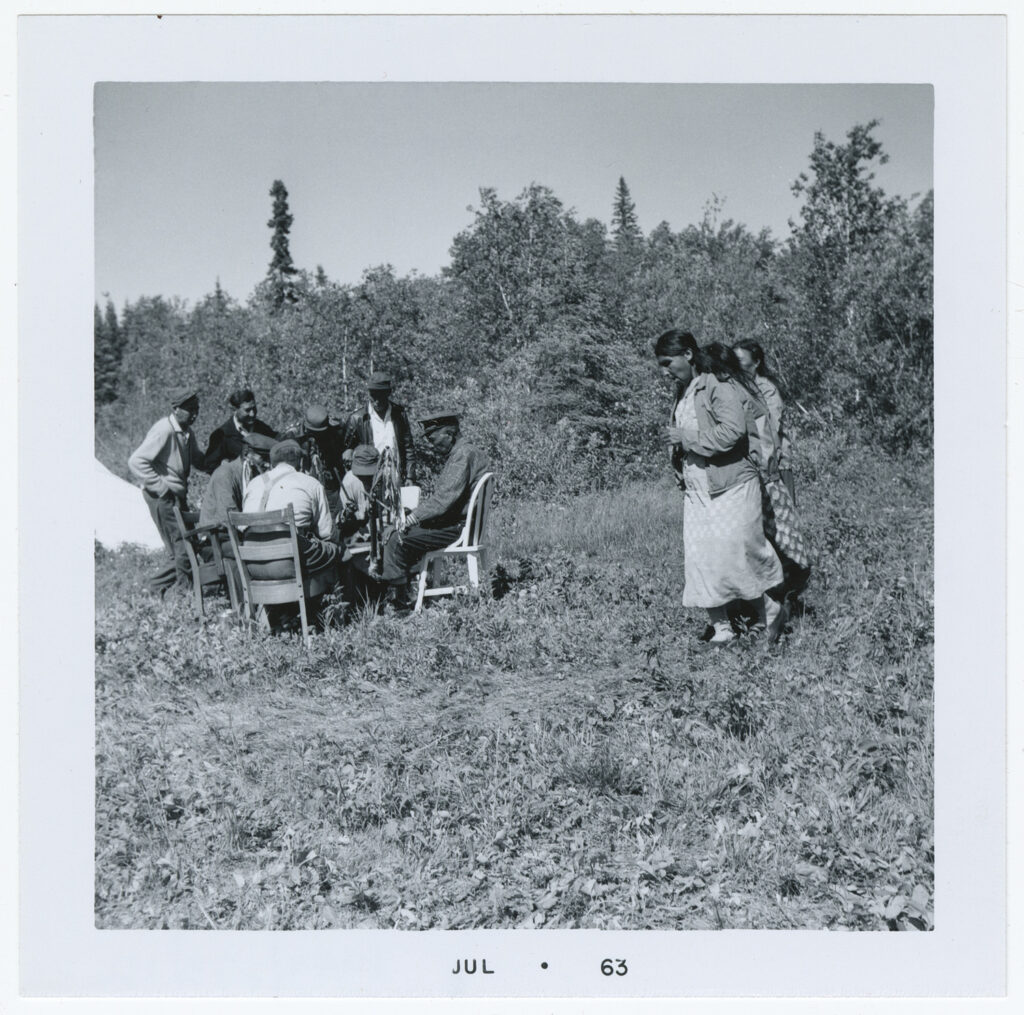

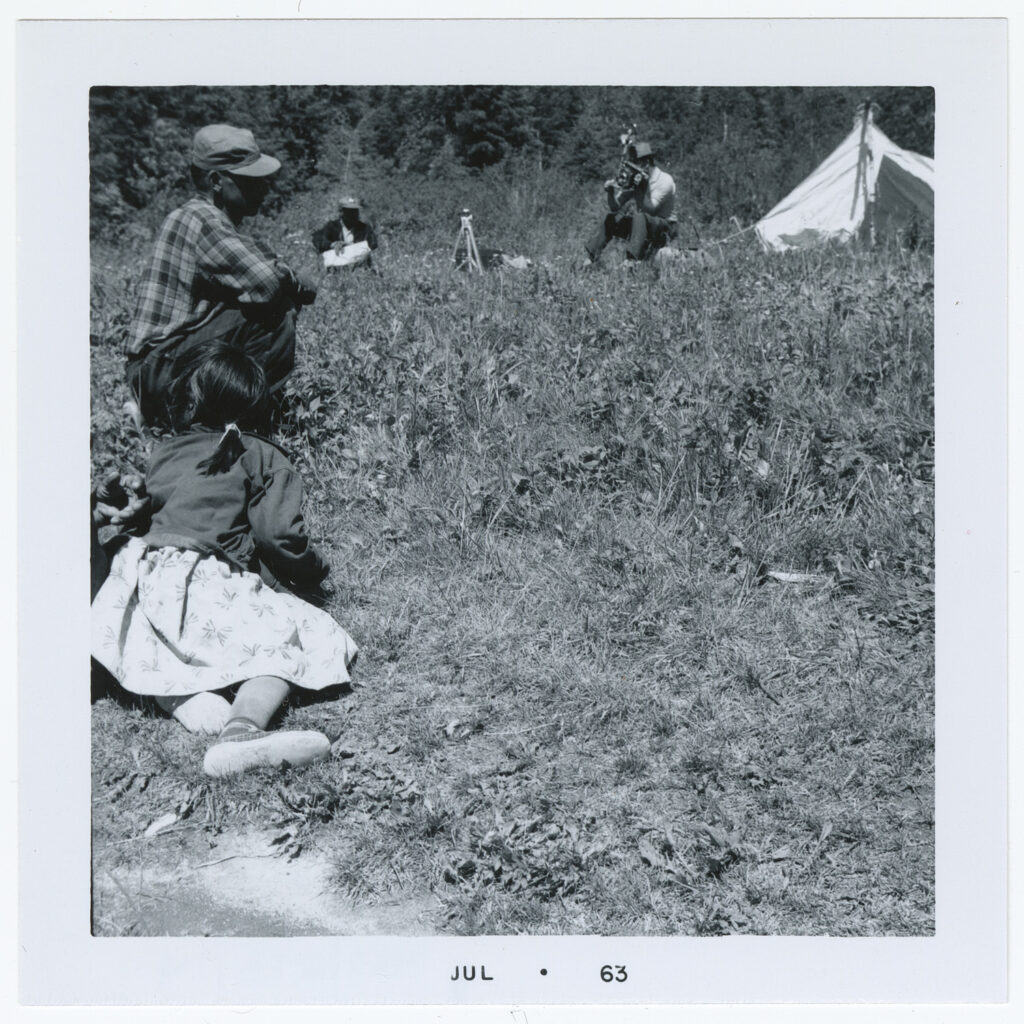

Don Ferguson fonds (1987/273). Photographer: Don Ferguson, 2 July 1963

Hudson’s Bay Company Archives, Archives of Manitoba

William Bones Leveque with pipe

William Bones Leveque (with pipe) and Chief Sam Bushie

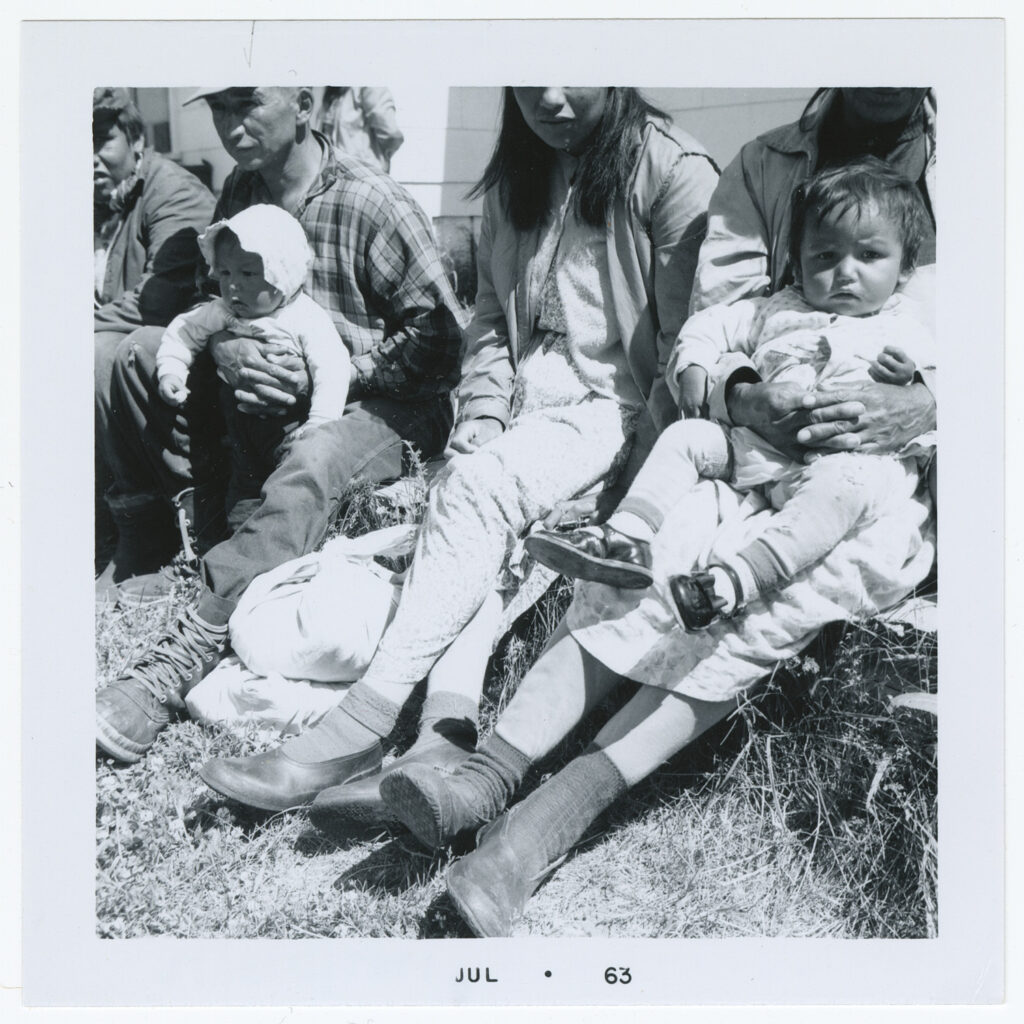

Observers. David Duck holding baby on left

Extreme left David Duck with 4 men dancing. At drum L to R: Bones, Bascombe, Bushie, Keeper. 4 women dancing: Louise Leveque, Sarah Leveque, Frances Bascombe, Marion Eaglestick

David Duck (interpreter on the left) and Robertson (photographer in back)

HBC post buildings

Bill Mayer Oakes

Remains of old HBC post across river from present post

Cemetery at Little Grand Rapids

In stern of boat Eric Dranthee, post manager Little Grand Rapids, clerk (only stayed 10 months with Company) Barry Tuckett

Hudson’s Bay House Photo Collection

Hudson’s Bay Company Archives, Archives of Manitoba

Thank you to the Pimachiowin Aki Director for Little Grand Rapids First Nation for your efforts to connect people of Pimachiowin Aki with our cultural heritage. Thank you also to drum keeper Carlisle Bushie and photographer Ōtake Hidehiro for making it possible for us to share images of the William Bones Leveque drum today, and to the staff of the Archives of Manitoba for providing Pimachiowin Aki with digitized copies of the audio recordings and photographs donated to the Archives.