This year, Pimachiowin Aki achieved several milestones that highlight the power of collaboration. Residents and visitors can now see new site signs, Guardians strengthened their skills through hands-on training, and communities are working to restore traditional place names for ancestral lands. We also welcomed new Board members, prepared to share our OUV in Anishinaabemowin, and launched our first online shop! These accomplishments reflect the dedication of communities and partners to care for the Land that Gives Life. Here are seven highlights:

1. New Signs on the Land

This summer, five new World Heritage Site signs appeared along PR 304, our very first in Manitoba! Manitoba Transportation and Infrastructure (MTI) worked with Pimachiowin Aki to design and install the signs, which mark the site boundary and help travellers find their way. These signs follow provincial road standards and UNESCO guidelines, making them official and built to last.

Pimachiowin Aki partners are grateful to everyone at MTI and UNESCO who helped bring this long-awaited project to life.

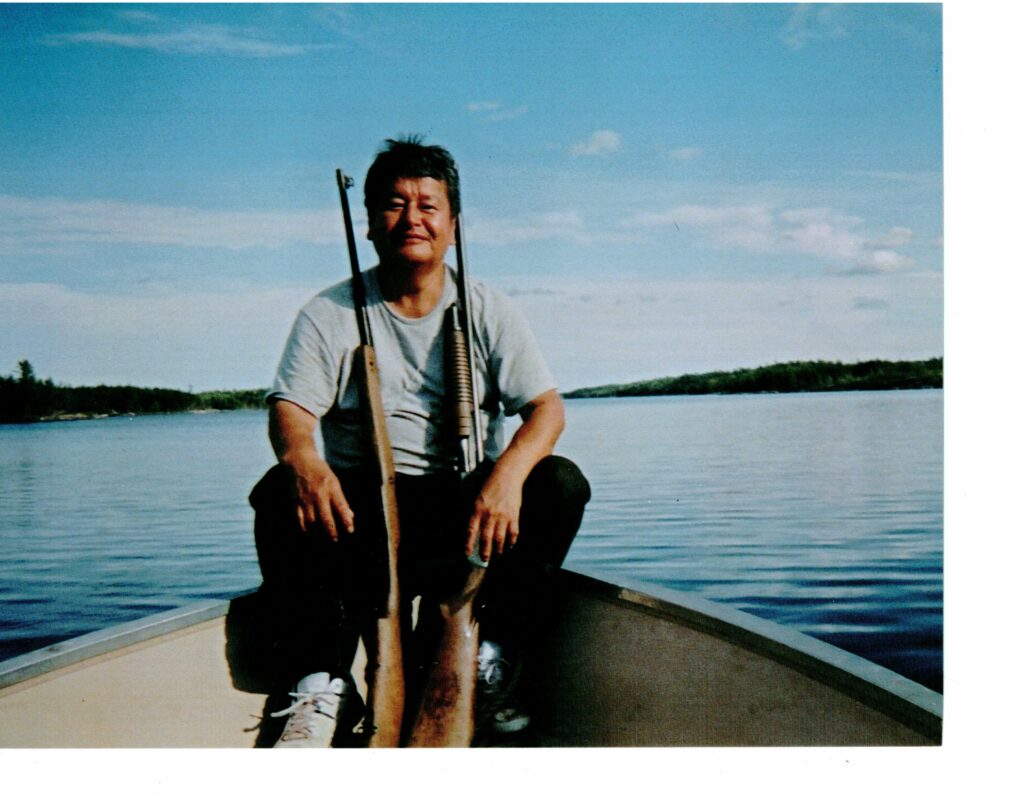

2. Guardians Complete 200-Hour Program

Pimachiowin Aki Guardians Melba Green and Owen Bear completed the intensive five-week Land Guardian Program through the Natural Resources Training Group. They attended lectures, trained in the field, learned to identify plants, birds, fish, wildlife and habitat, and sharpened their environmental monitoring skills.

The program strengthens the important work happening right now in Bloodvein River and Poplar River, provides opportunities for future employment in land management and environmental protection, and meets academic requirements for an Applied Biology Technician program.

Congratulations, Melba and Owen!

3. New Leaders Join the Board

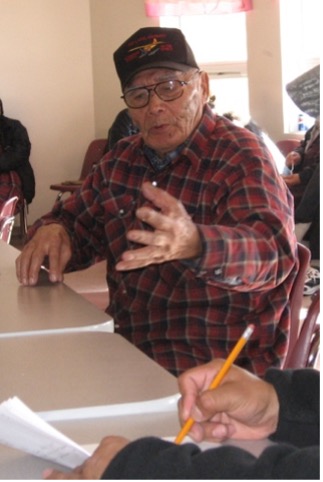

Enil Keeper

Little Grand Rapids First Nation has a new representative on the Board. Enil Keeper—former Chief, long-time Councillor, RCMP officer, assistant Conservation Officer, Home-School Coordinator, and lifelong learner—brings deep community knowledge and decades of experience to this position. Born on Sharpstone Lake and raised on the land, Enil has been part of the Pimachiowin Aki journey from the beginning. He follows Augustine Keeper, who contributed more than a decade of leadership and vision.

Rob Nedotiafko

Rob Nedotiafko was appointed to represent the Government of Manitoba on the Board of Directors. Rob worked closely with Poplar River First Nation on the Asatiwisipe Aki Land Management Plan and now serves as Director of Parks for Manitoba Environment and Climate Change. He steps into the role held for 16 years by Bruce Bremner, whose dedication continues to shape our work today.

Waajiye/Welcome, Enil and Rob

Aapiji miigwech/Many thanks to Bruce and Augustine

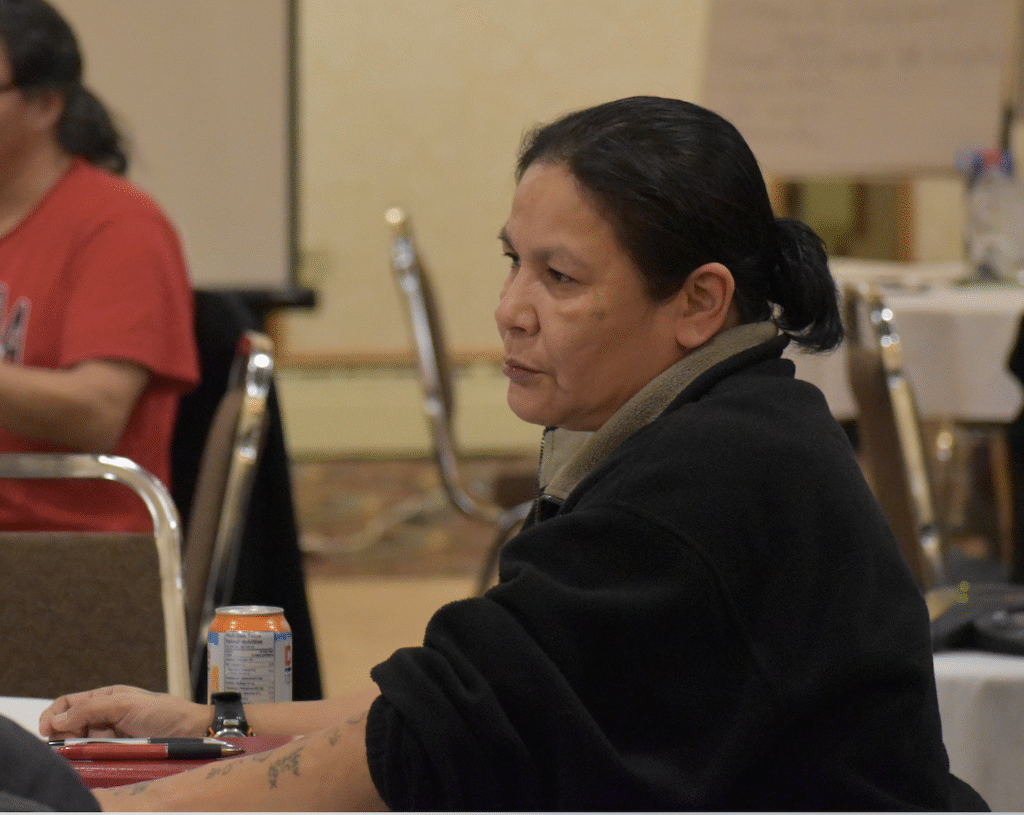

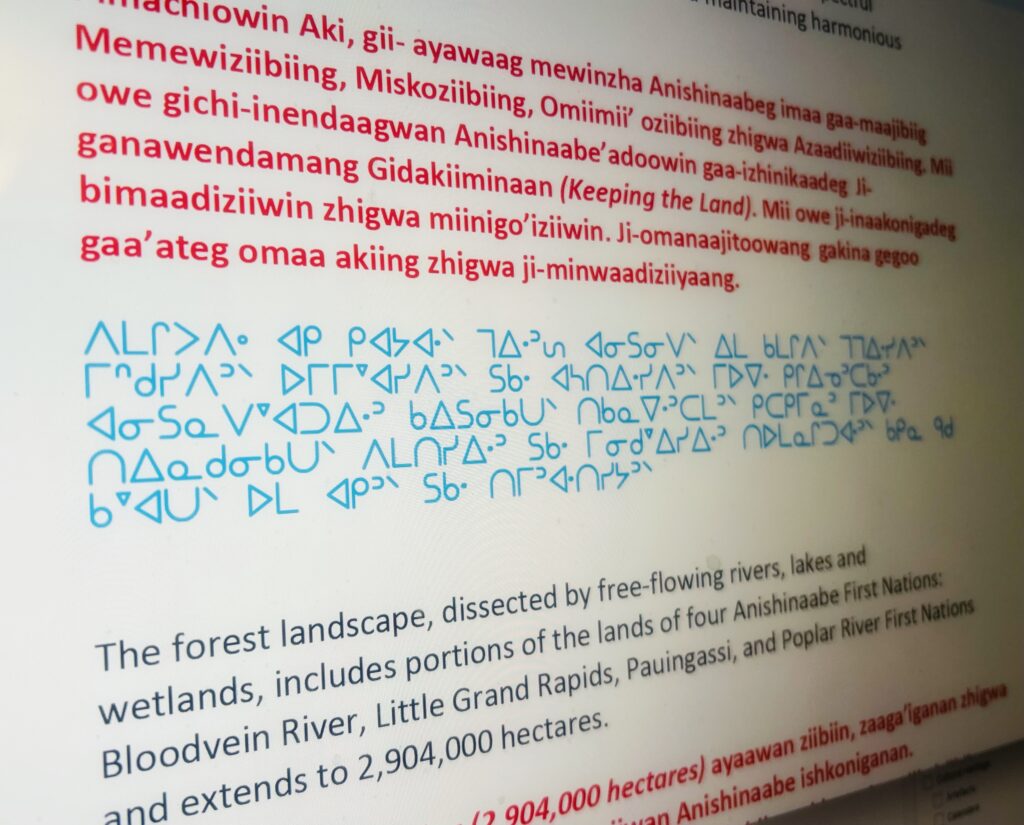

4. Our OUV—Now in Anishinaabemowin

Pimachiowin Aki’s Statement of Outstanding Universal Value (OUV) will soon be available in Anishinaabemowin—in Roman orthography and syllabics. This translation, completed by Carol Beaulieu and supported with a grant from Parks Canada, brings the language of the land to this important UNESCO text.

The OUV explains why Pimachiowin Aki matters to the world and has cultural and natural significance for all peoples, now and for future generations.

The translated version will be shared on our website and with schools once approved by Pimachiowin Aki partners. Please contact your Director if you would like to review the draft statement.

Outstanding Universal Value means cultural and/or natural significance which is so exceptional as to transcend national boundaries and to be of common importance for present and future generations of all humanity. As such, the permanent protection of this heritage is of the highest importance to the international community as a whole.

—para. 49, Operational Guidelines for Implementation of the World Heritage Convention

Carol shares her story about the translation process > Guided by Teachings—Carol’s Approach to Translation

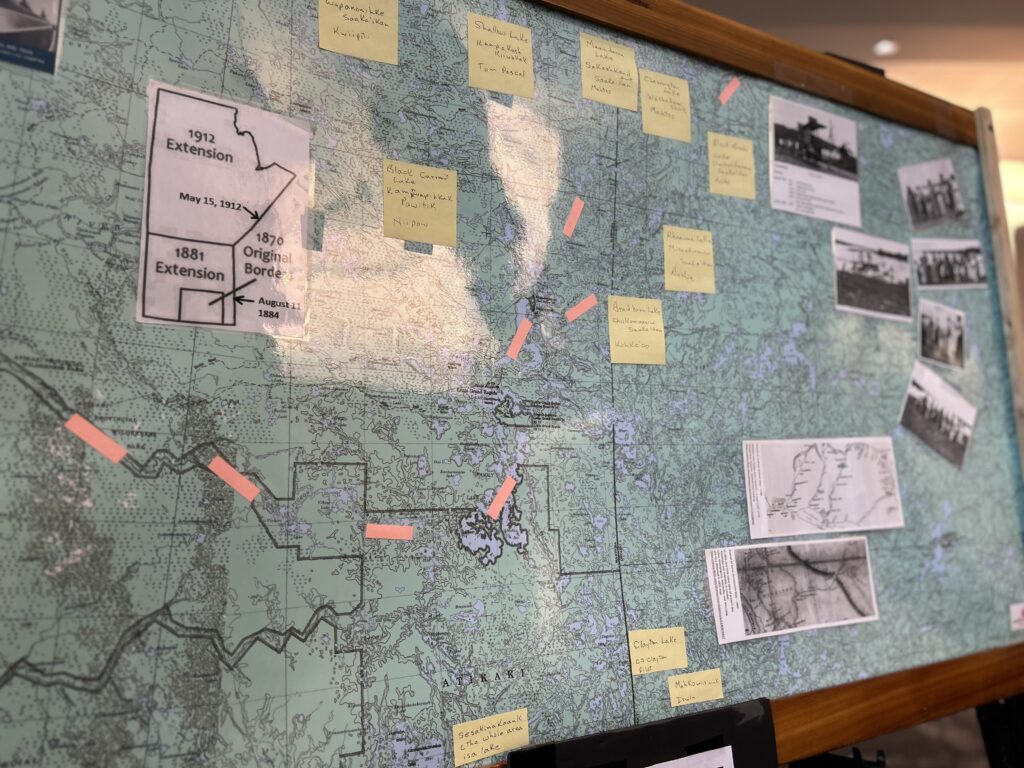

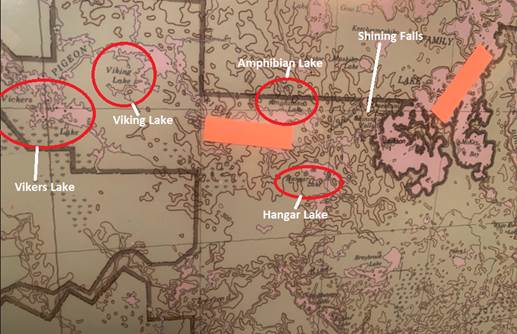

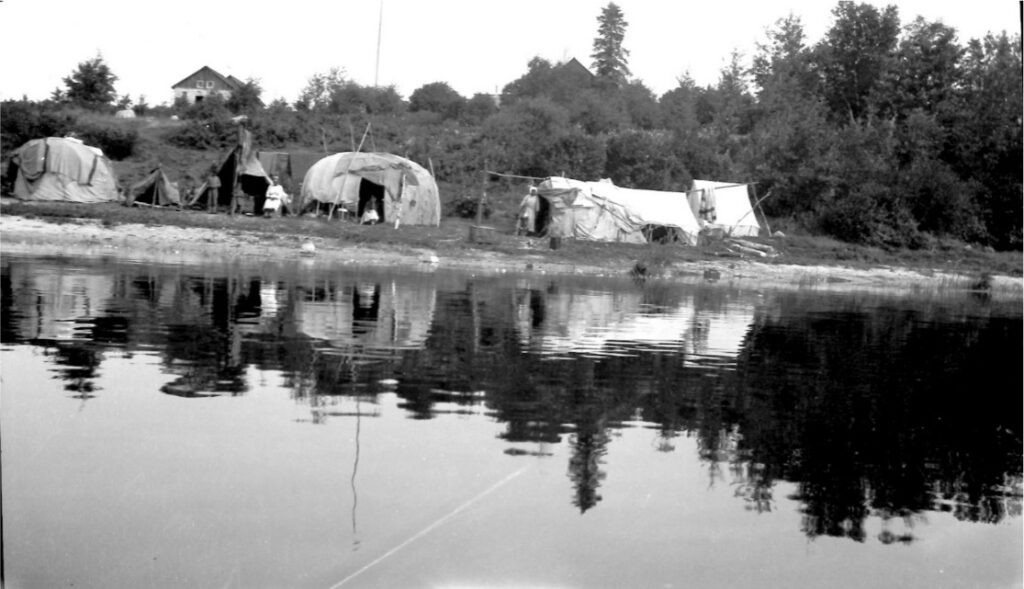

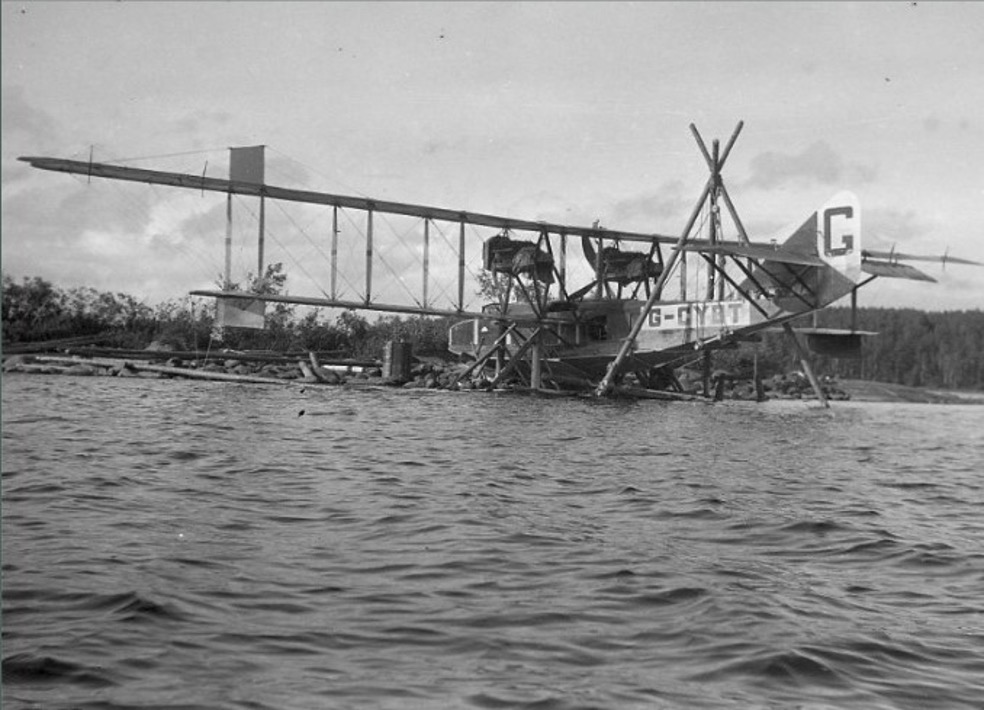

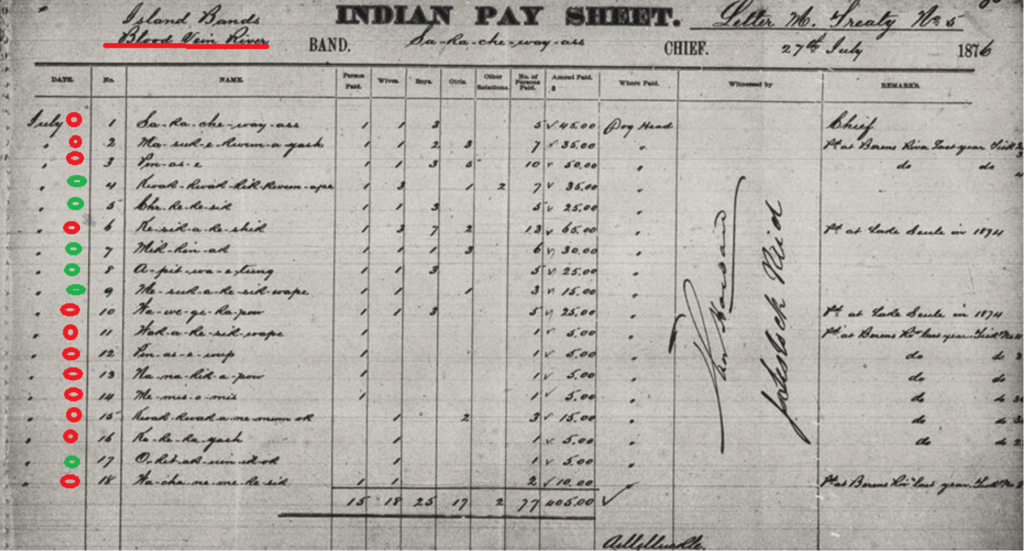

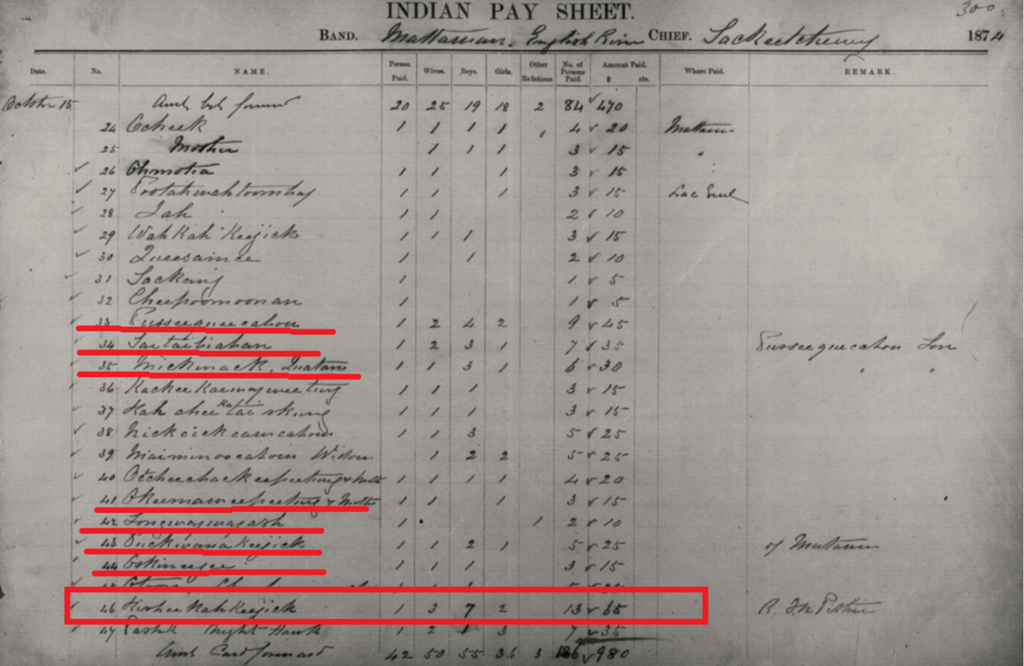

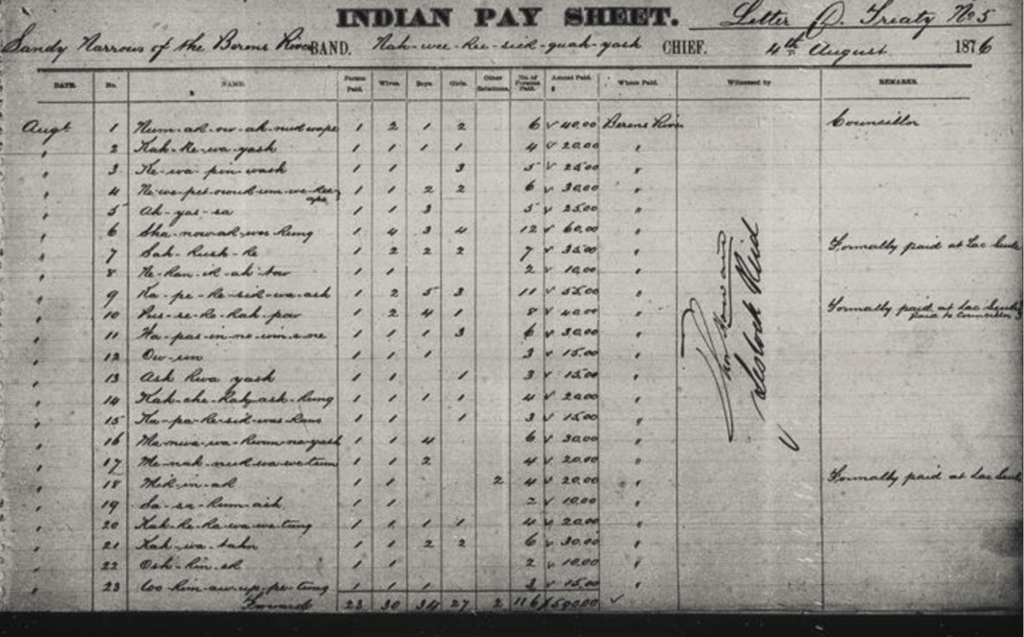

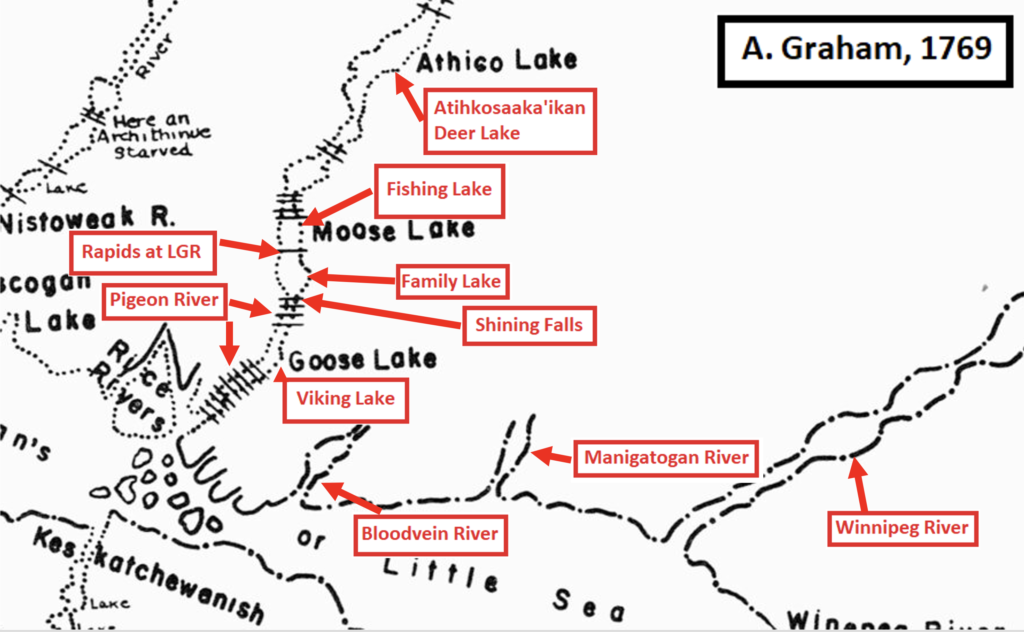

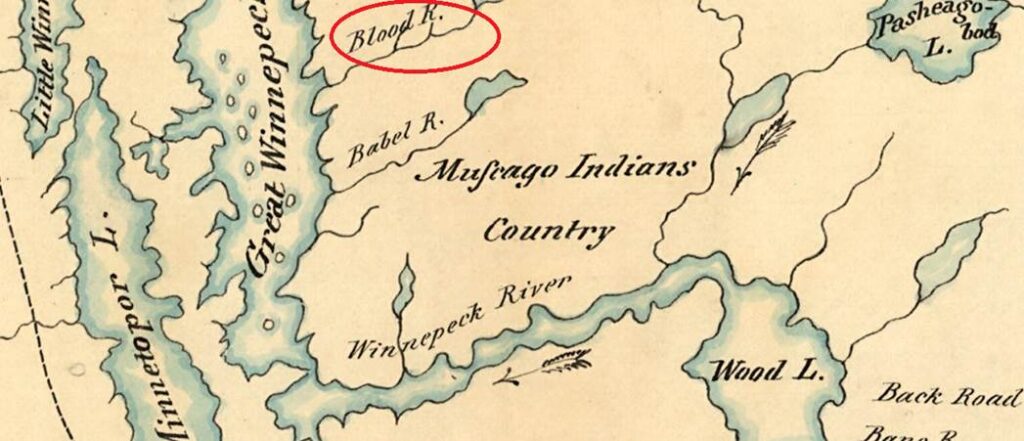

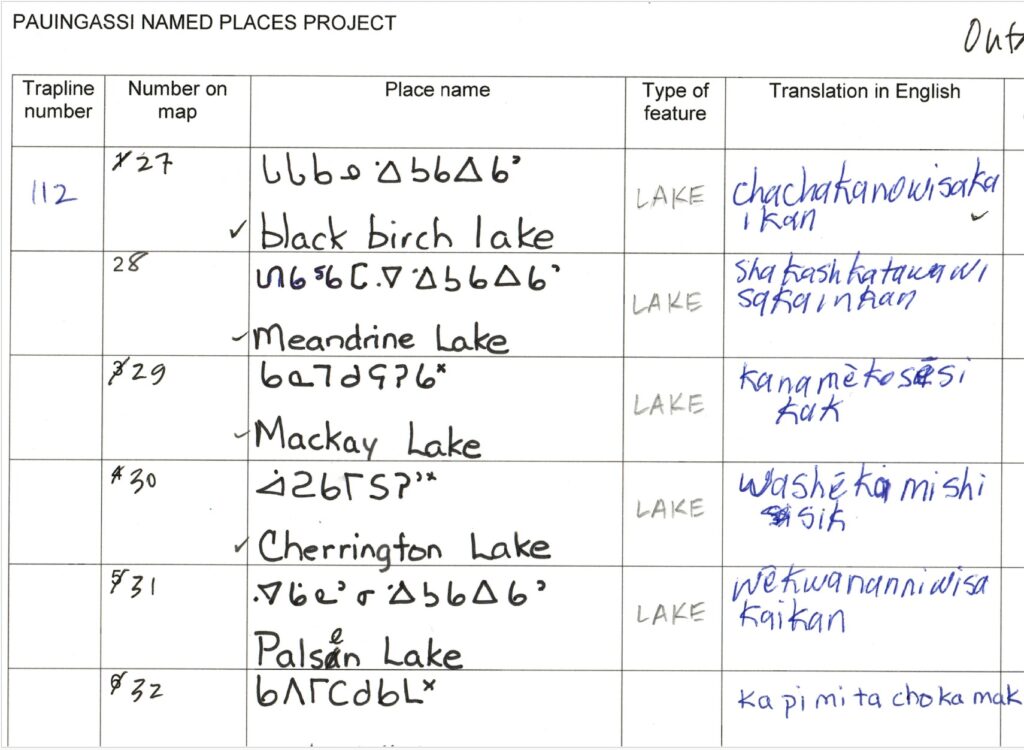

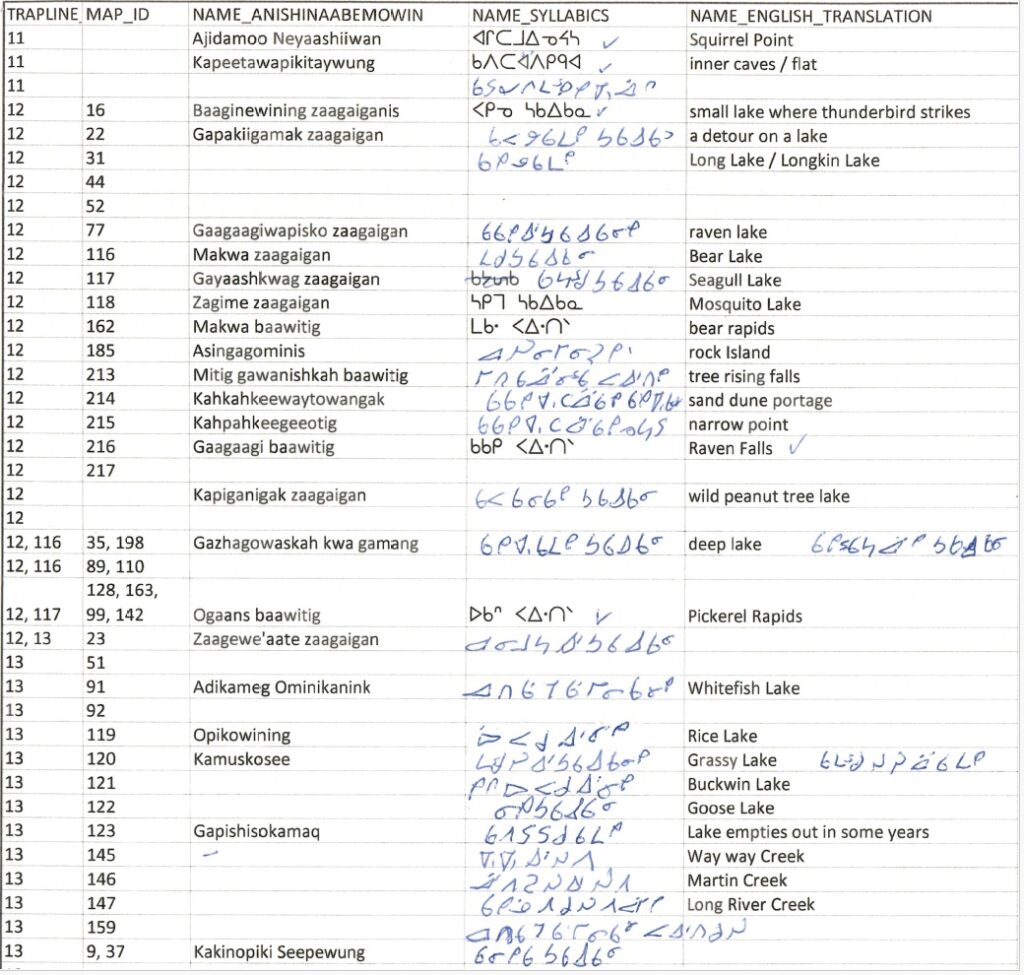

5. Bringing Traditional Place Names Back to the Map

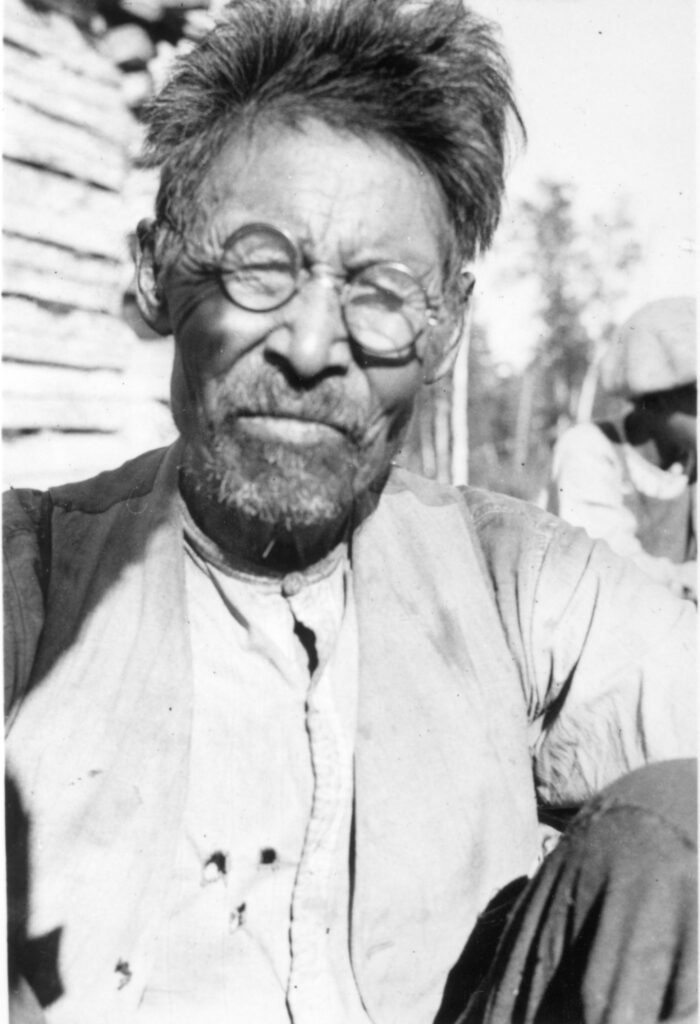

Little Grand Rapids and Pauingassi First Nations continued their Traditional Place Names Projects this year, working with Elders, knowledge keepers, Manitoba’s Provincial Toponymist, and a Master’s student. Draft maps are now ready for community review—the moment where Elders confirm spellings, stories, and accuracy.

Once complete, maps will be shared in schools and community spaces. The First Nations will also decide which names to make official so they can appear on Google Maps and future topographical maps.

Miigwech to Manitoba’s Lands and Planning Branch for providing GIS mapping support and helping this project grow.

6. A Top Score for Pimachiowin Aki

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) World Heritage Outlook assesses the health of natural and mixed World Heritage Sites every 3–5 years. In 2025, Pimachiowin Aki received the highest possible conservation outlook.

Drawing on insights from hundreds of experts and partners, this global assessment tracks the state of conservation of all natural and mixed World Heritage sites and raises awareness of their importance. It also serves as an early warning system, helping identify threats and guide actions needed to safeguard the world’s wonders.

Pimachiowin Aki’s outlook is a powerful reminder that when communities, governments, Guardians, and supporters work together, we can protect one of the world’s most important ecosystems and cultural landscapes. The full report is available here: https://worldheritageoutlook.iucn.org/explore-sites/pimachiowin-aki

7. Our New Online Shop

Pimachiowin Aki has launched an online store! For now, supporters who donate $300 or more to the Pimachiowin Aki World Heritage Fund at The Winnipeg Foundation receive a copy of Obaawingaashiing Gichi-Aabijitaawinan – The Pauingassi Collection as a thank-you gift. Miigwech to everyone who made this possible, including:

- Maureen Matthews, Elaine and Joshua Owen, (late) Roger Roulette, and Carol Beaulieu for creating the book

- Manitoba Museum for publishing the book as part of the Nametwaawin Outreach Project funded by Heritage Canada with a contribution from Pimachiowin Aki

- A donor-advised fund at The Winnipeg Foundation for a significant contribution toward the cost of printing the books

- Peaceworks Technology Solutions for programming our new Shop page

- Everyone who invested in Pimachiowin Aki this year through your donations, grants to our programs, and in-kind contributions. We thank you for placing your trust in us to steward these resources and maximize their impact

Every Dollar Helps Protect Pimachiowin Aki

In the future, we hope to offer books, maps, posters, and even branded apparel directly through the Shop to support our programs.