Pimachiowin Aki was inscribed on the World Heritage List on July 1, 2018 during the 42nd session of the World Heritage Committee in Manama, Bahrain.

It has been an exciting five years since Pimachiowin Aki became Canada’s first mixed UNESCO World Heritage site. With so many incredible moments to choose from, it was difficult to decide which ones to celebrate with you today. We are humbled and proud to share these highlights:

1. Guardians Network is established

When Pimachiowin Aki launched its Guardians Network in 2018, we had no idea how quickly the program and Guardians’ capacity would grow. In addition to monitoring the lands and waters of Pimachiowin Aki, Guardians have documented and shared customary laws, recorded place names, collaborated with researchers, operated drones, spoken at conferences, conducted bird surveys and recorded bird songs, harvested food for Elders, taken youth on land-based learning trips, and more. We thank you for your care of people and places, for connecting with the land and each other, and for sharing your knowledge and skills. You have strengthened our communities and are a gift to us all.

Pimachiowin Aki Corporation was one of 28 successful applicants in Canada for the early round of funding from the Environment and Climate Change Canada Indigenous Guardians Pilot Program in 2018. The program has since secured annual funding and established the Pimachiowin Aki Guardians Fund to carry it into the future.

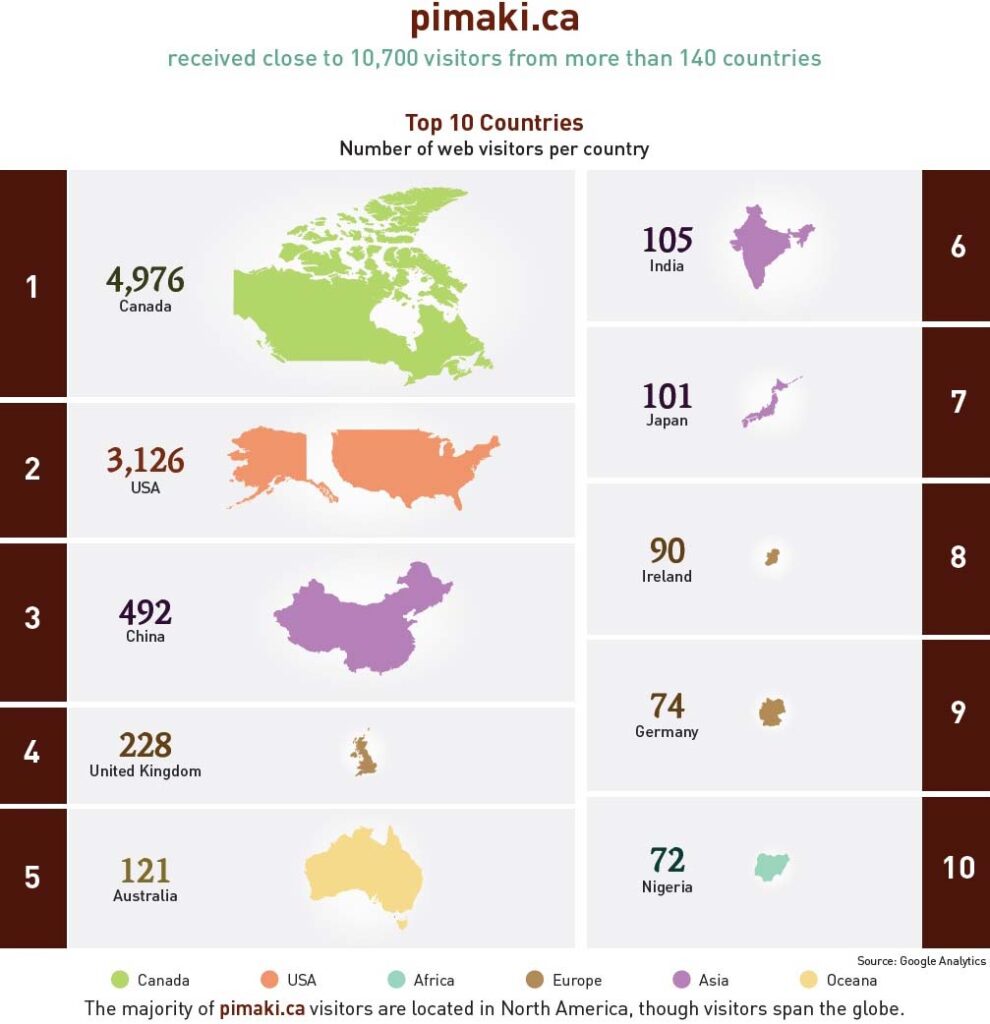

2. The World Visits pimaki.ca

World Heritage status creates a tremendous opportunity to enhance understanding of Pimachiowin Aki’s cultural and natural values and share these values with the world. Since the launch of our newly designed and reprogrammed website, Pimachiowin Aki has been sharing information about The Land that Gives Life with people from around the globe. The new website has received many positive reviews, including praise for the amount and quality of information and how easy it is for people to find what they’re looking for.

The website even caught the eye of Dr. Gemma Faith, who, at the time, was a PhD researcher at Ulster University in Northern Ireland. Gemma made Pimachiowin Aki the focus of her research, which won an Outstanding PhD Thesis award. Gemma’s thesis explored how pimaki.ca communicates the unique bond that Anishinaabeg have with the land to people around the world.

3. The Pimachiowin Aki Endowment Fund Hit $5 Million

For the first time since it was established in 2010, the fund reached its highest-ever value of $5 million last year. Thank you to our generous donors who have helped us reach this milestone. Your donations help grow the fund, which is held at The Winnipeg Foundation. Annual revenue from the fund helps Pimachiowin Aki operate the Guardians Network, create and support cultural heritage education and Indigenous knowledge programs, provide training and capacity-building, and lead and support research to ensure that the world understands and respects this special place and all who live here.

Pimachiowin Aki is a small not-for-profit charitable organization with big ideas, and a mission to safeguard Pimachiowin Aki for the well-being of Anishinaabeg and the world, forever.

4. We Built a Digital Library

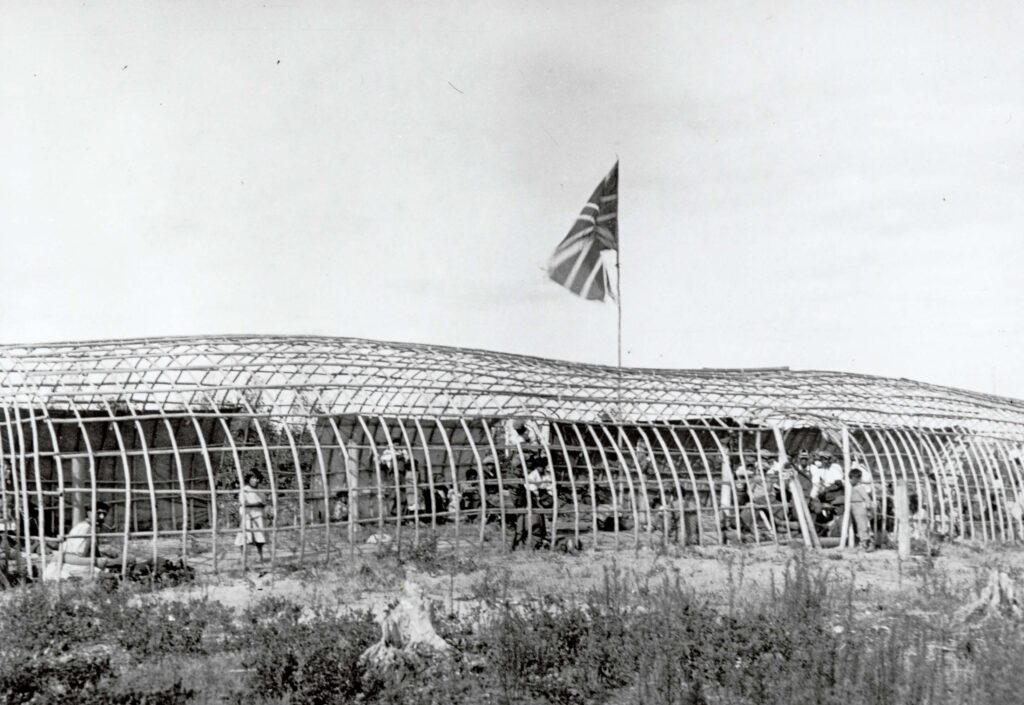

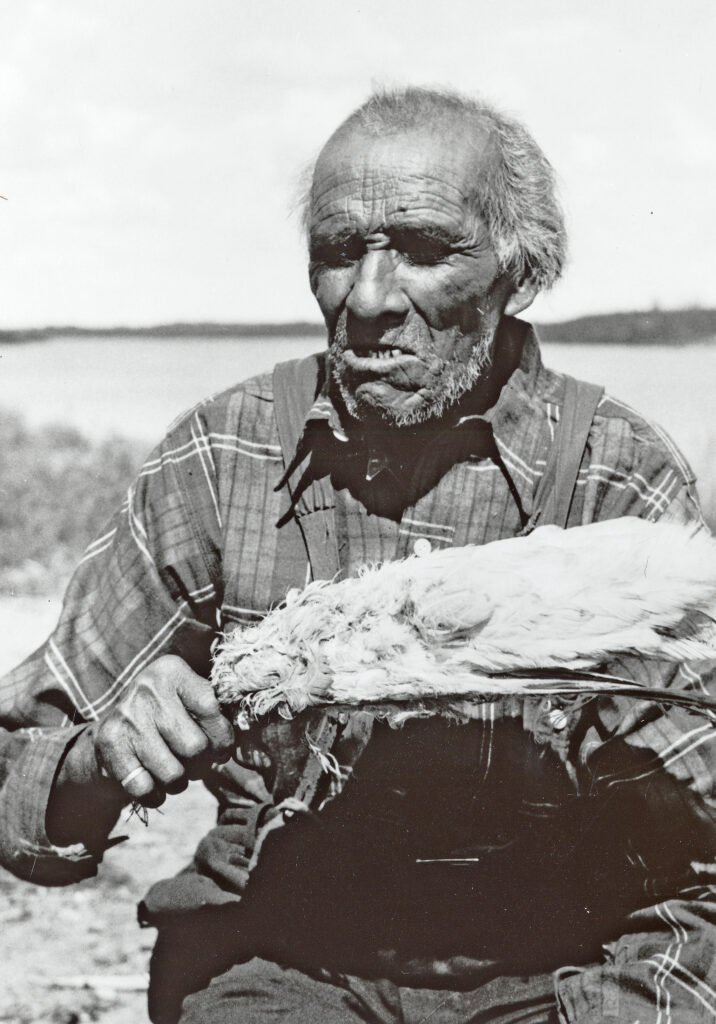

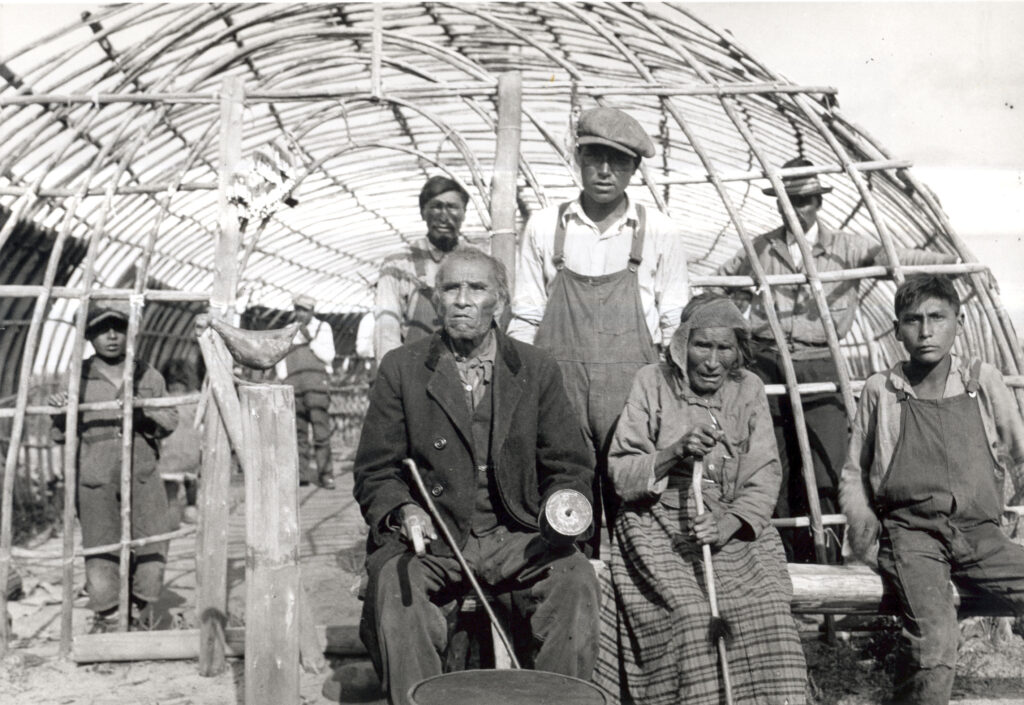

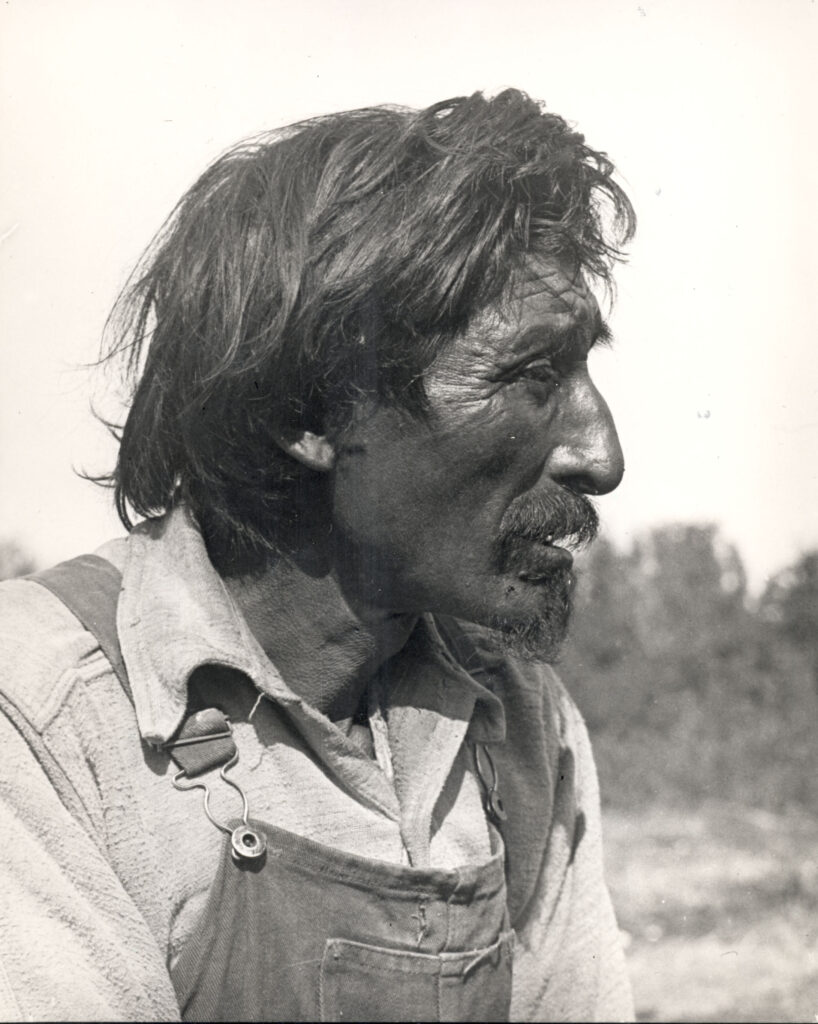

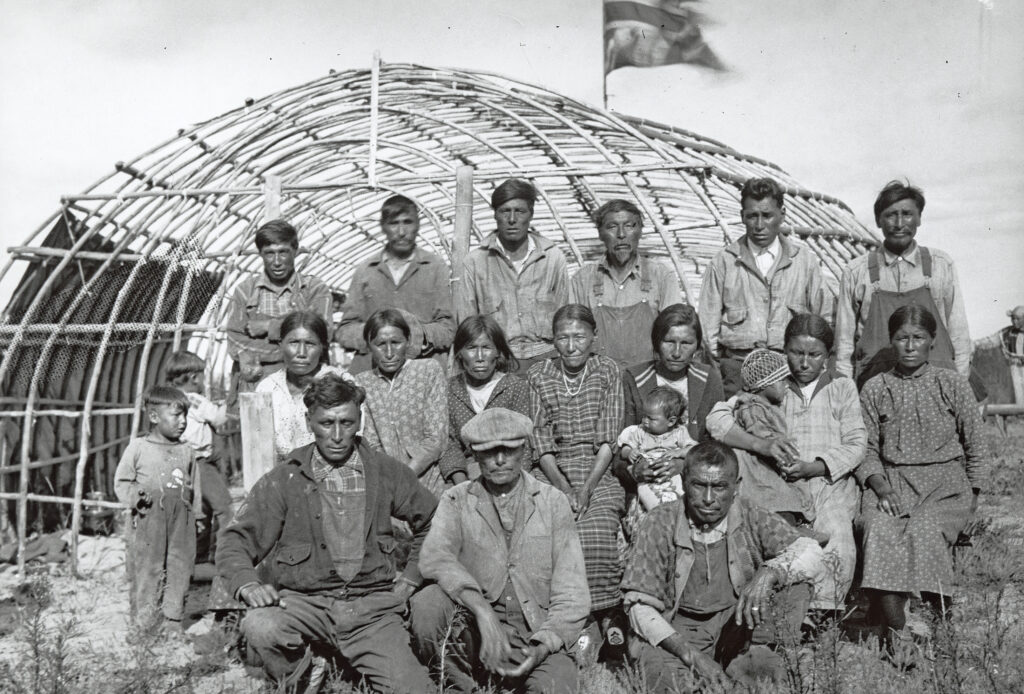

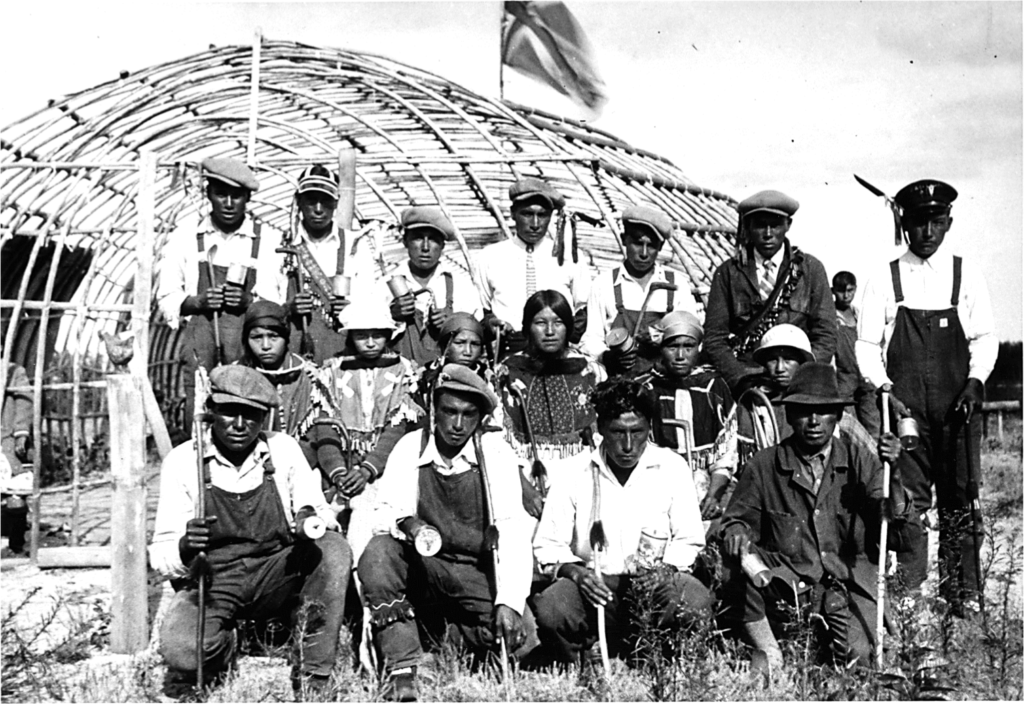

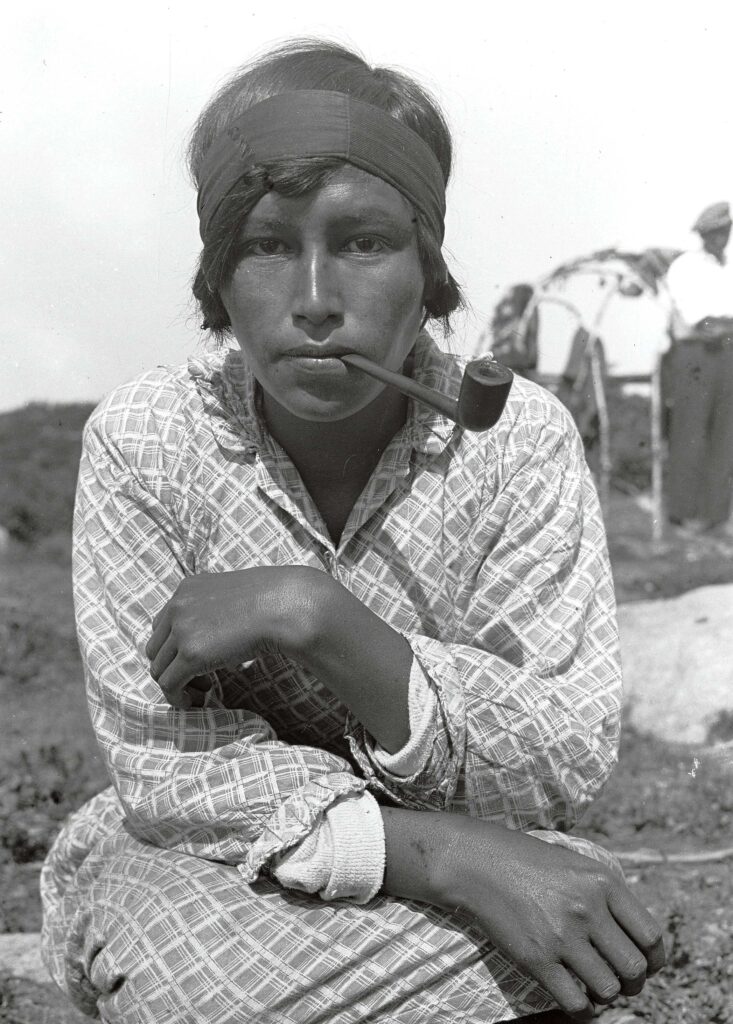

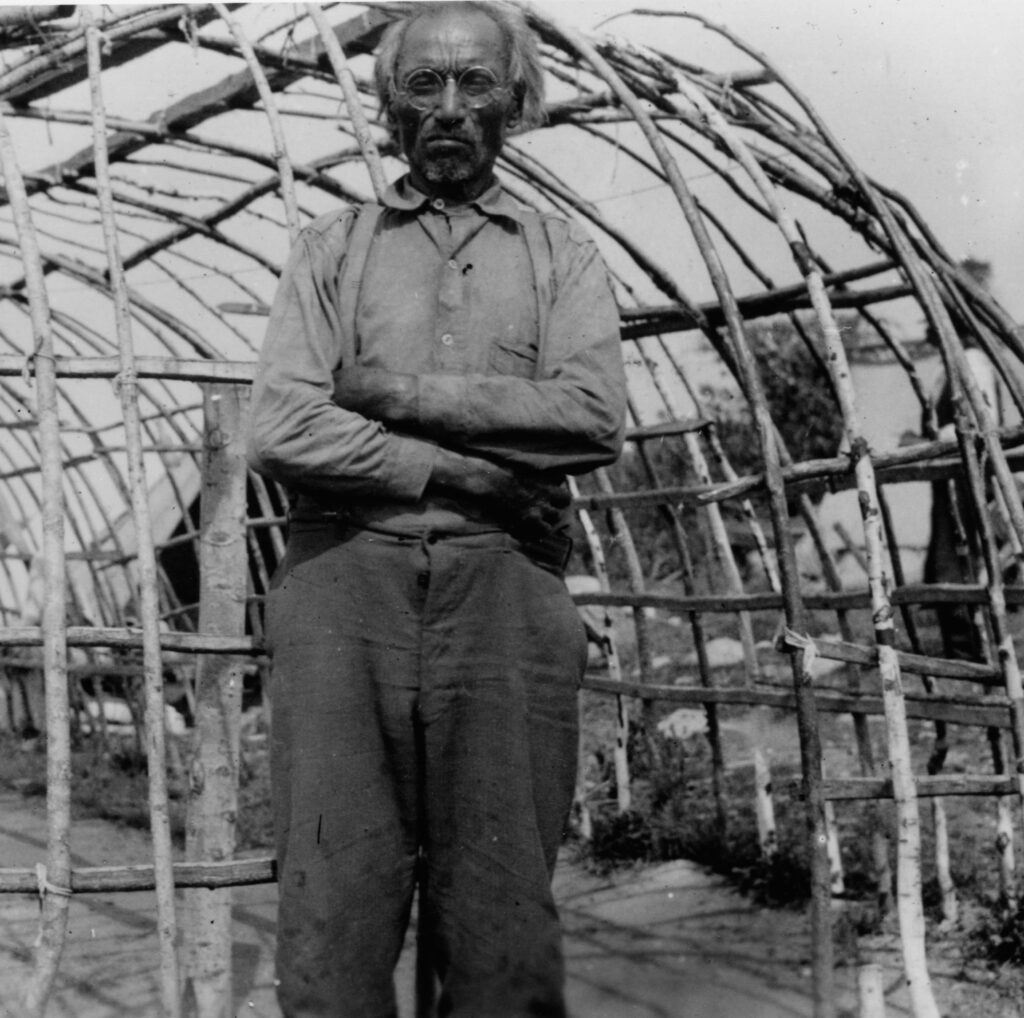

Along the journey to becoming a UNESCO World Heritage site, we acquired over 12 thousand photos of the people and places of Pimachiowin Aki. For over two decades, people involved in the project have been documenting their experiences and sharing photos – from large community gatherings to wildlife sightings to touring UNESCO representatives on evaluation missions across the waters of Pimachiowin Aki. Many of the photos you see in our communications date back to this time.

Today, these photos, along with a vast amount of information and data collected for First Nations’ land use planning and the World Heritage site nomination, are neatly accredited and organized into folders in the Pimachiowin Aki digital library. The library continually grows as Guardians, community members, professional photographers, researchers and visitors share photos and information with us.

The Pimachiowin Aki library is an important achievement as it provides a fuller picture of the World Heritage site and offers layers and layers of information. Each time Pimachiowin Aki creates a map, such as place names maps, more detail and meaning is added from our library.

The extensive library also provides local teachers with valuable information as they incorporate the cultural, natural and educational values of Pimachiowin Aki into their curricula.

5. We Published Bilingual Anishinaabemowin/English Books

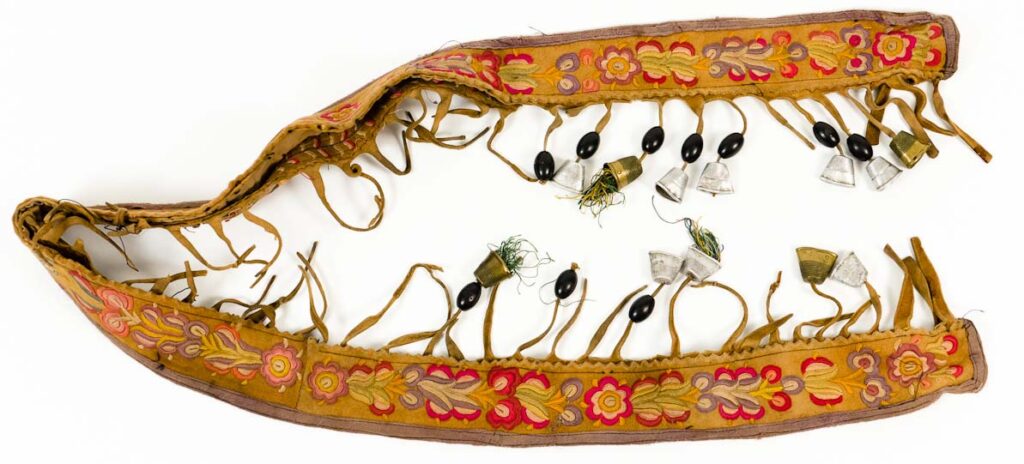

In partnership with Manitoba Museum, we contributed research and expertise developed during First Nations’ land use planning and the World Heritage site bid to create resources for schools in the Pimachiowin Aki communities.

The project is coming to completion, and five books will soon be delivered to all schools in Pimachiowin Aki, and potentially to every school in Manitoba. The books will be also available for purchase at Manitoba Museum. The books are:

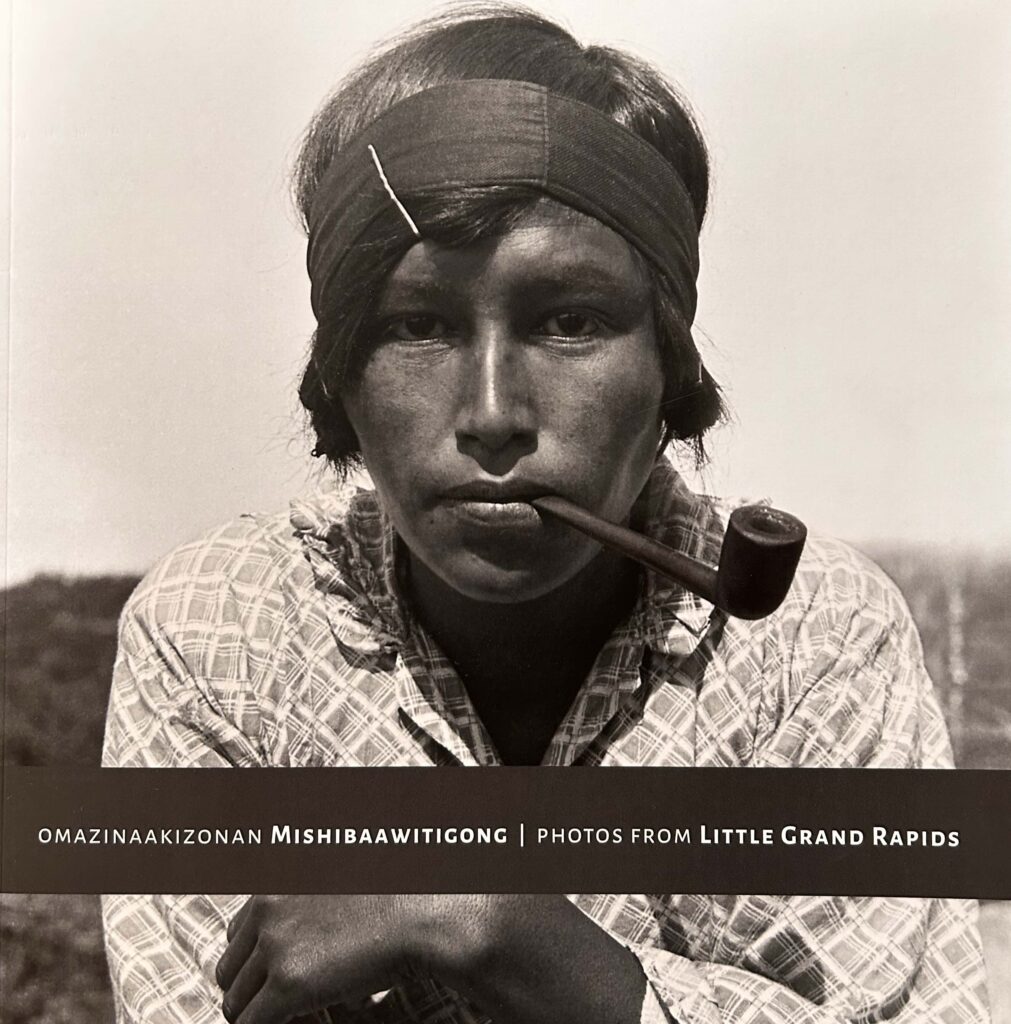

- Omazinaakizonan Mishibaawitigong | Photos From Little Grand Rapids

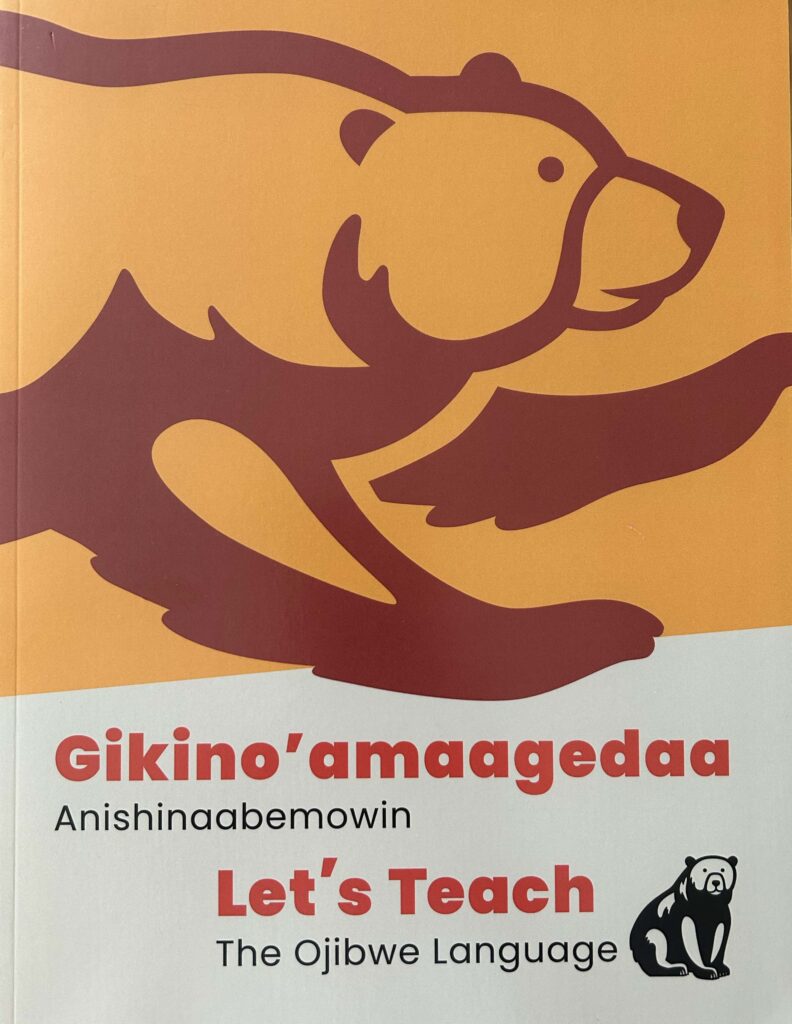

- Gikino’amaagedaa Anishinaabemowin | Let’s Teach the Ojibwe Language

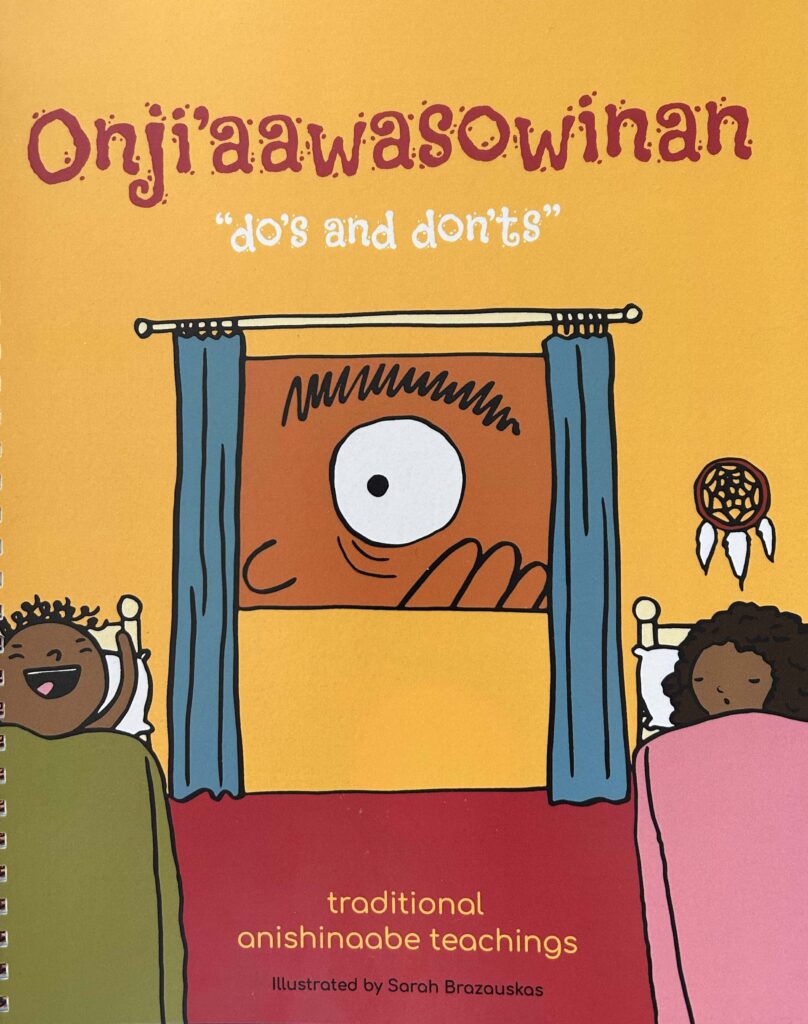

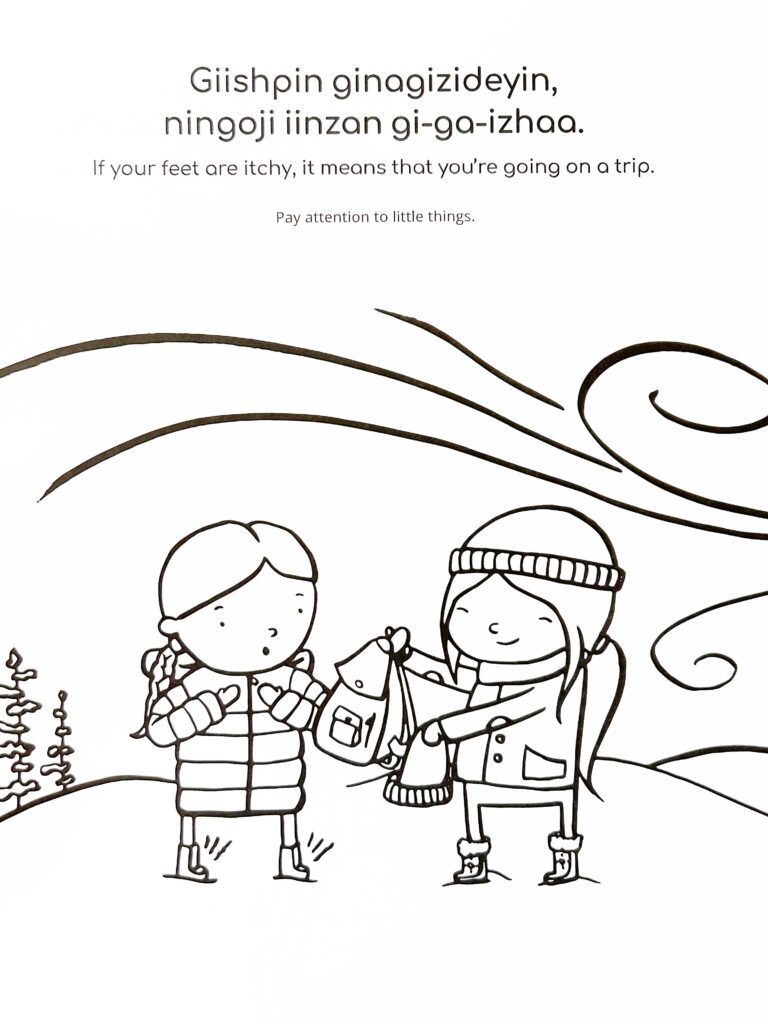

- Onji’aawasowinan | “do’s and don’ts“ Traditional Anishinaabe Teachings (colouring book)

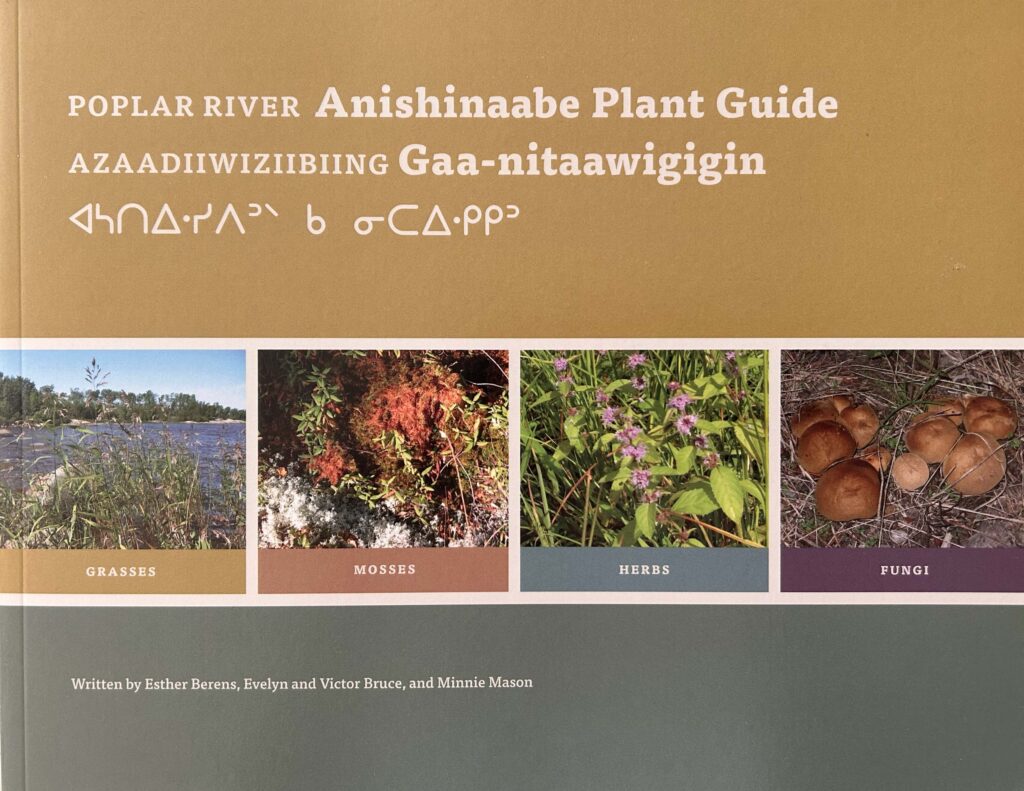

- Azauuwiziibing Gaa-nitaawigigin | Poplar River Anishinaabe Plant Guide

- Obaawingaashiing Aabijichiganan | Pauingassi Collection

Thank you to our two special donors whose generosity helped to finish this project.

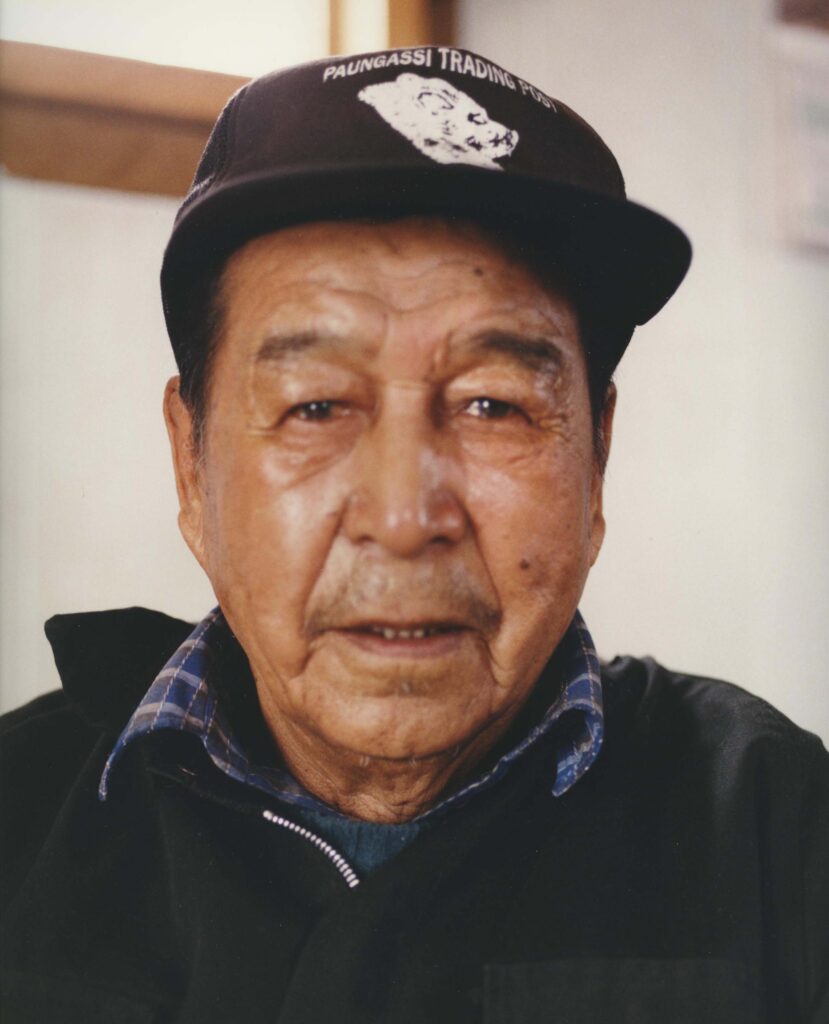

This is what the children should be taught. That they should never forget their Anishinaabe language, the way the language was spoken long ago.

OMISHOOSH (ELDER CHARLIE GEORGE OWEN), PAUINGASSI FIRST NATION

Shop

Shop