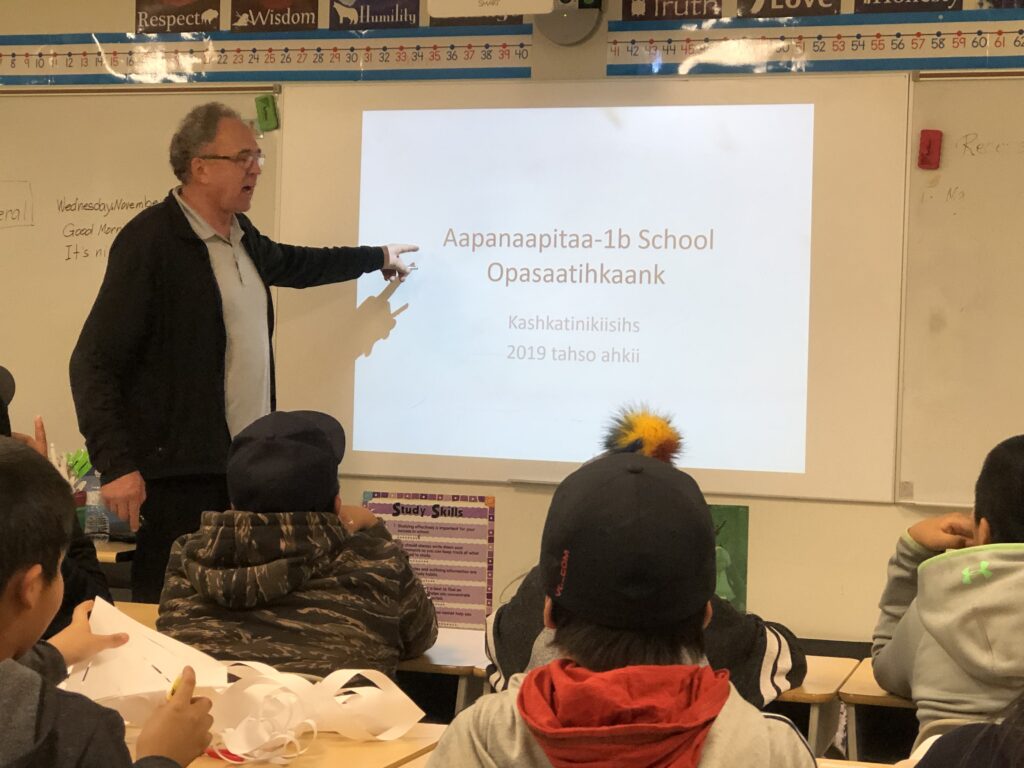

For years, Gerald Neufeld (Kaahkaapish) has been researching original names of people and places in the Pimachiowin Aki area and sharing his discoveries.

He quoted George Orwell while presenting a slide show at the recent Pimachiowin Aki AGM in Winnipeg. “The most effective way to destroy people is to deny and obliterate their own understanding of their history.”

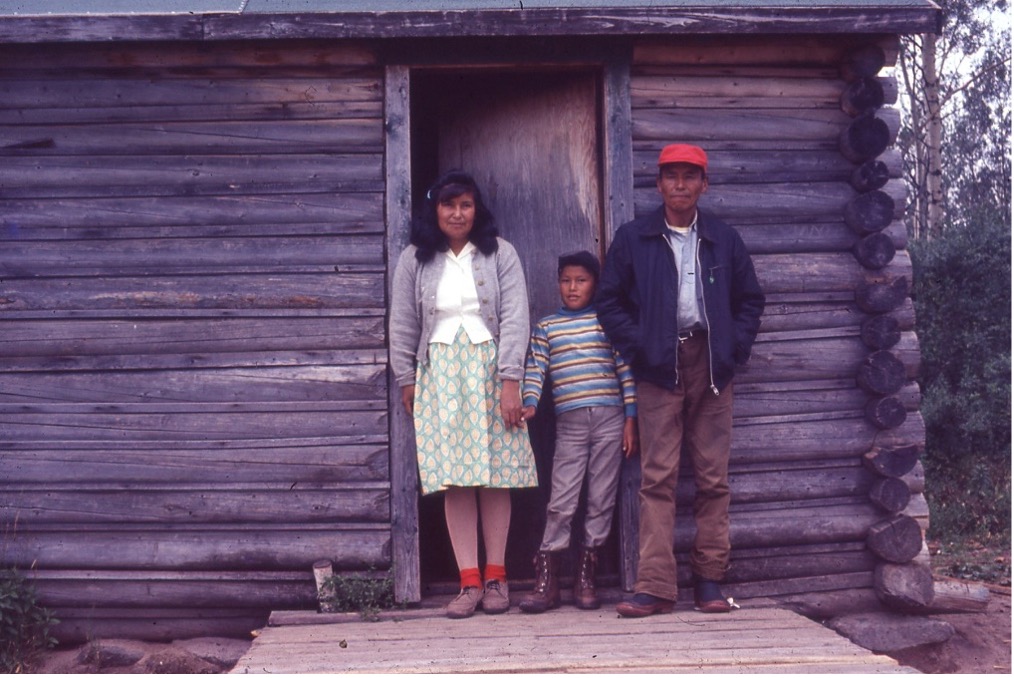

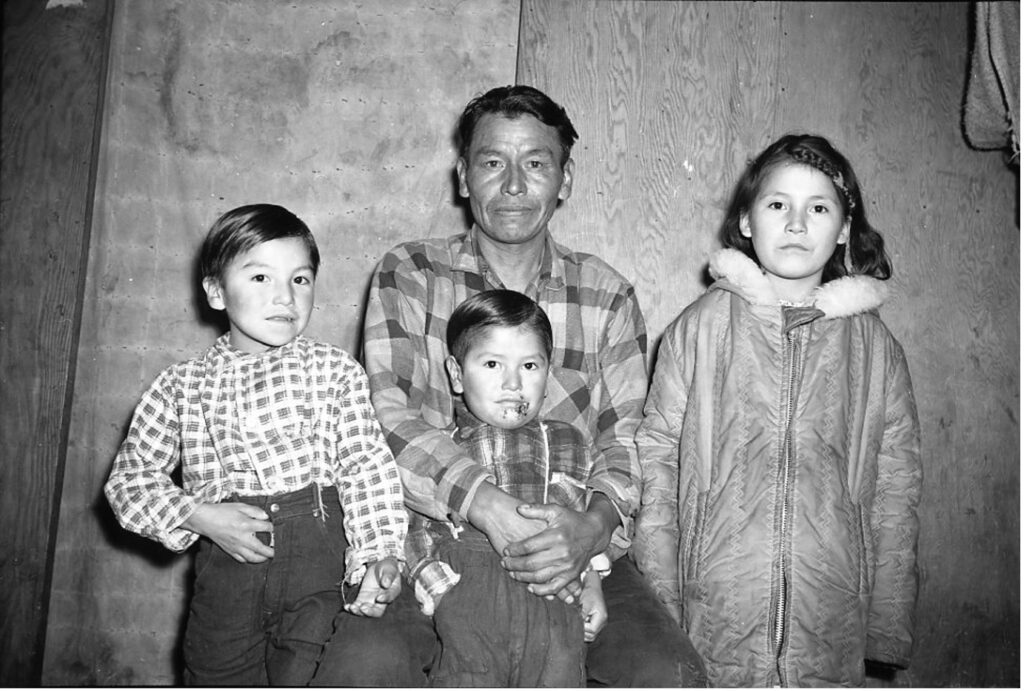

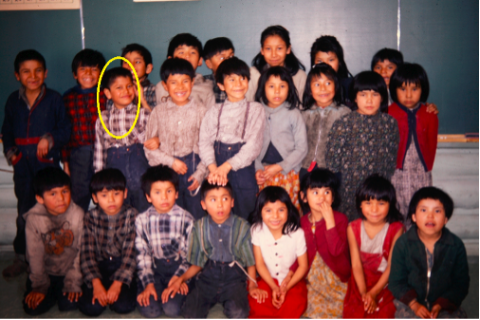

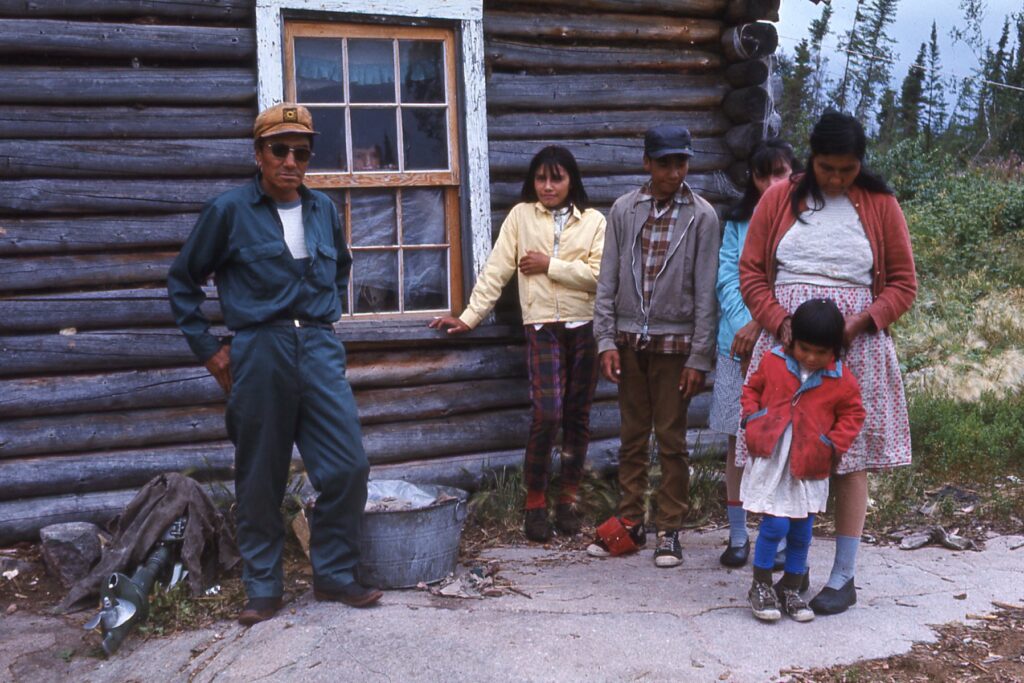

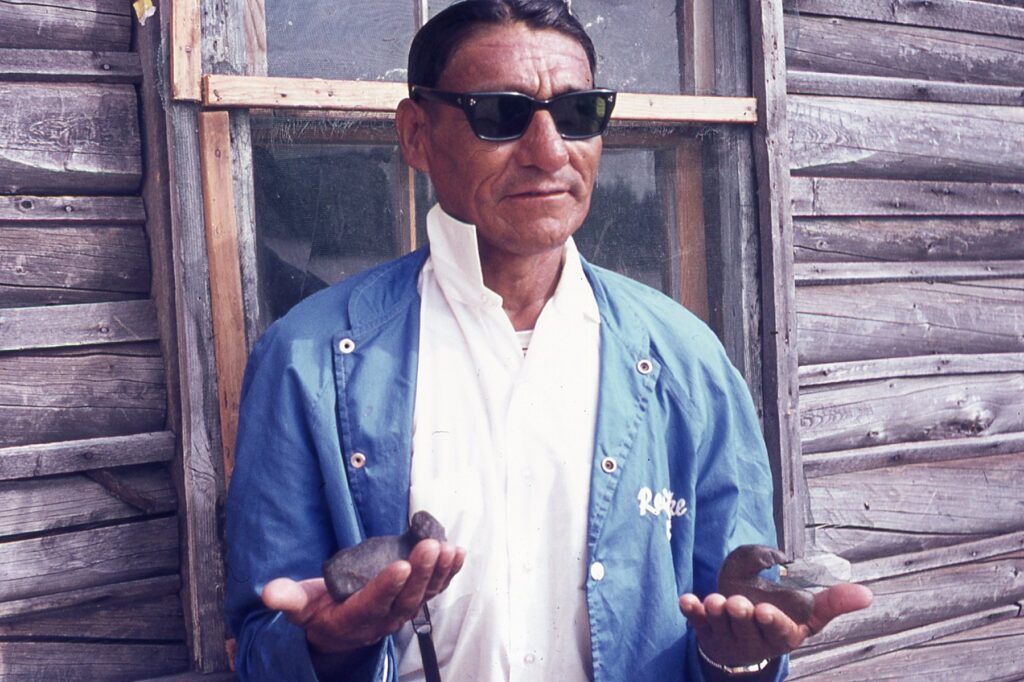

Gerald grew up in Pauingassi First Nation and has been working with his father Henry (Ochichaahkons), Elders, and community members in Pimachiowin Aki to restore “histories that have been erased through time.”

He described his research as a slow process, but one that is essential to reclaiming cultural identity and heritage. “Sometimes, it’s like molasses in January to figure this out,” he said.

He said his discoveries are made possible by the earlier work of anthropologist A. Irving Hallowell, who visited the Berens River Ojibwe in the 1930s and Gary Butikofer, who taught at Poplar Hill Development School in the 1970s.

Here’s what we learned from his presentation:

1. Lakes near Little Grand Rapids were named after aircraft

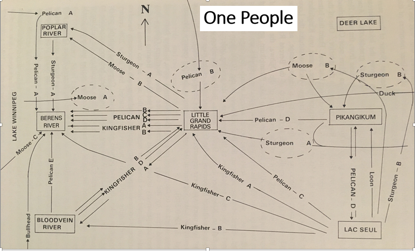

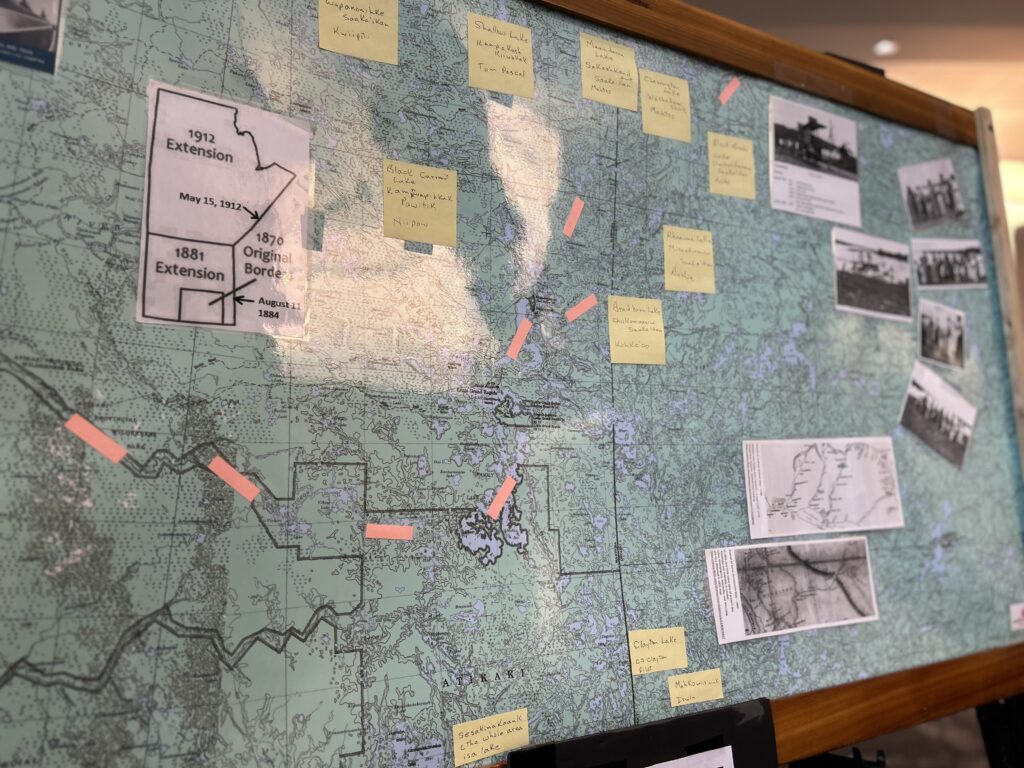

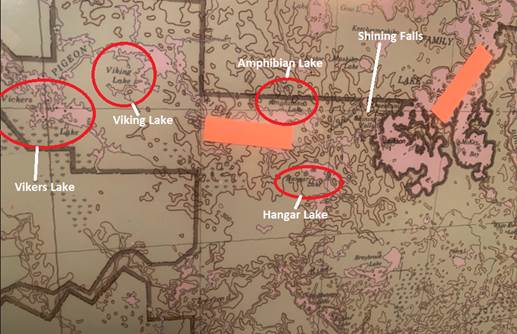

Vickers Viking amphibian aircraft first arrived in Canada in 1922 and in the years following, “planes were active in the [Pimachiowin Aki] area,” said Gerald. “We can see that lakes near Little Grand Rapids were named after them,” he said while pointing out four lakes on a map:

- Viking Lake

- Vickers Lake

- Amphibian Lake

- Hangar Lake

More Lake Names

If you click this link and scroll down to page 17, you’ll find a long list of Manitoba lakes in alphabetical order with details on who or what they were named after. The list includes English and Indigenous names. Examples:

Abraham Lake (64 A/9) North of Split Lake. CPCGN records (1975) indicated this to have been named after Abraham Wavey who trapped in this area years ago.

Ameekwanis Lake (64 K/13) Northeast of Reindeer Lake. A Cree name meaning small spoon.

Amphibian Lake (52 M/13) West of Family Lake. Named in 1926 after the type of aircraft used in photographing the area (Douglas 1933).

Kosapachekaywinasinne (64 C/7) Locality southeast of Lynn Lake. CPCGN records (1979) indicated that this name was Cree meaning looking inside rock. Apparently old people used to go to this place to see into the future.

Kokasanakaw River (53 M/8) Flows northeast into Swampy Lake. A local Cree name meaning lots of fish.

Makataysip Lake (53 D/14) Southeast of Gunisao Lake. A local Saulteaux name meaning black duck.

Makatiko Lake (62 P/9) North of the Bloodvein River. CPCGN records (1978) indicated it to be a local Native name meaning crippled deer.

Vickers Lake (52 M/13) On Pigeon River west of Family Lake. GBC records (1926) indicated that the name was adopted over the common local name Goose Lake. It was the name of the company that manufactured the aircraft used to photograph the area. Goose Lake had been recorded on maps from possibly A. Graham (post 1771; HBC) onwards, although often in the wrong position. GBC correspondence (1929; from the Hudson’s Bay Company) listed the local name Big Goose Lake.

2. Aircraft Changed How Maps Were Made

“This is Amphibian Lake. There’s the airplane, there’s the flying boat, and there’s the camera. They would take photograph after photograph—boom, boom, boom, as they flew along—and they would give that to the mapmakers.”

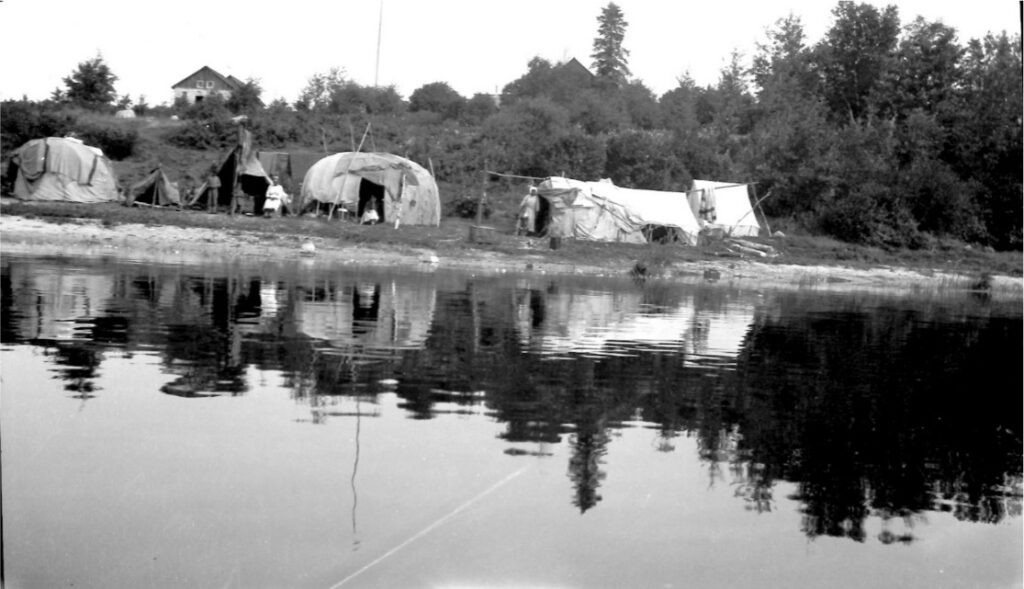

By using photos taken from the sky, mapmakers were able to create maps that were more accurate and detailed. Gerald described a photo from a 1924 aerial survey, showing the Bloodvein River.

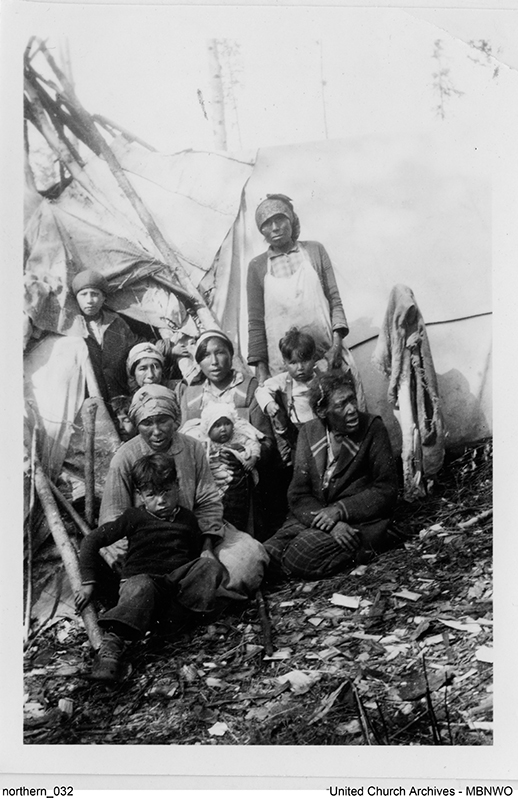

“It is hard to see much here but I circled an area that shows some white spots. You have to look closely, but I think these spots may be dwellings.”

Bloodvein Aerial Photo, Royal Aviation Museum of Western Canada, marked up by Gerald

“That’s what people lived in back in the day. These white tents are dwellings.”

Little Grand Rapids, 1925, J.W. Pierce, DLS

3. Maps changed how people traveled

The ability to map the area from the sky was a significant technological leap, but the shift also led to a disconnect from the traditional ways that people identified and traveled the land.

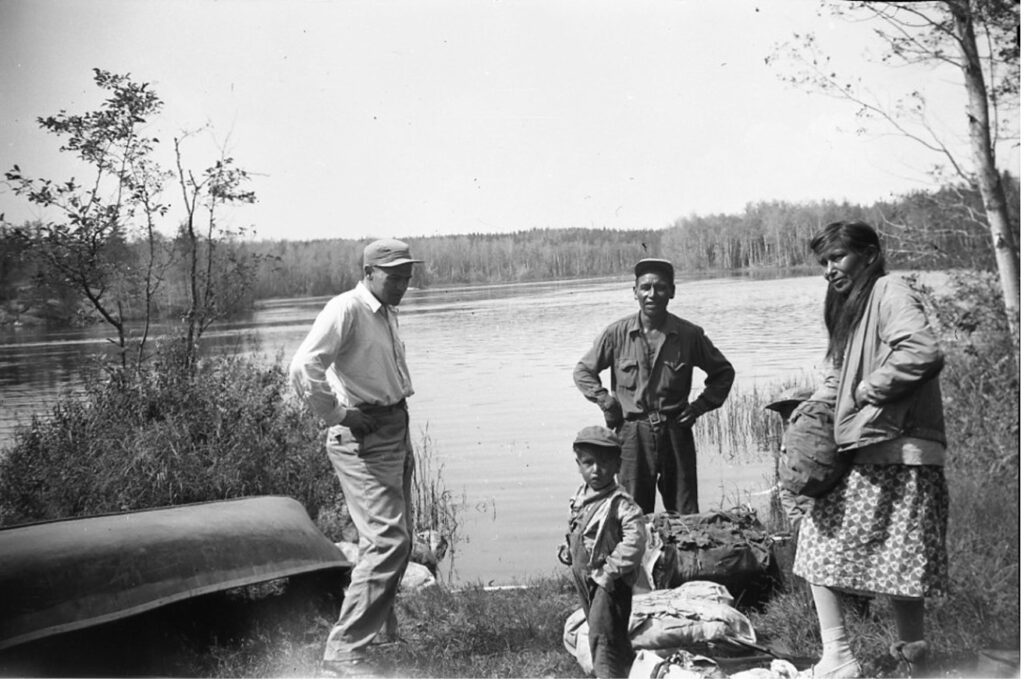

“In earlier years, people from the area travelled east-west along the Berens and Bloodvein rivers,” said Gerald. “The rivers were the primary passageways.” Gerald explained that several factors disrupted this over time.

The slow growth of change began with the assignment of the Manitoba-Ontario boundary in 1912. This was followed by the introduction of aircraft. Also, Manitoba and Ontario no longer shared responsibilities for communities. “Eventually, Education and Health services expanded according to provincial jurisdiction,” said Gerald.

“Over time, commercial airplane operations and transportation routes were established, and these ran north-south. Travel increased immensely since then, but east-west travel is almost non-existent. Also, we have transitioned from light-weight, birch bark canoes to heavier alumunium boats with larger motors. These boats are heavy and much more difficult to portage, making the use of traditional travel routes difficult.”

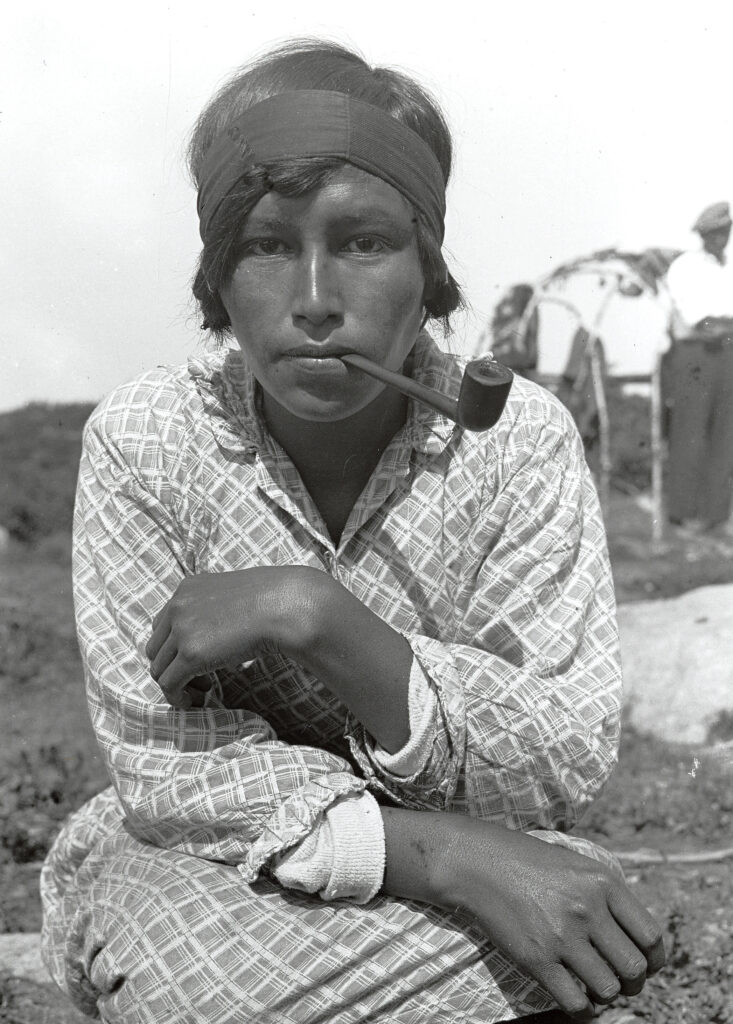

4. Pikangikum residents named the first-ever plane to land there Big Duck

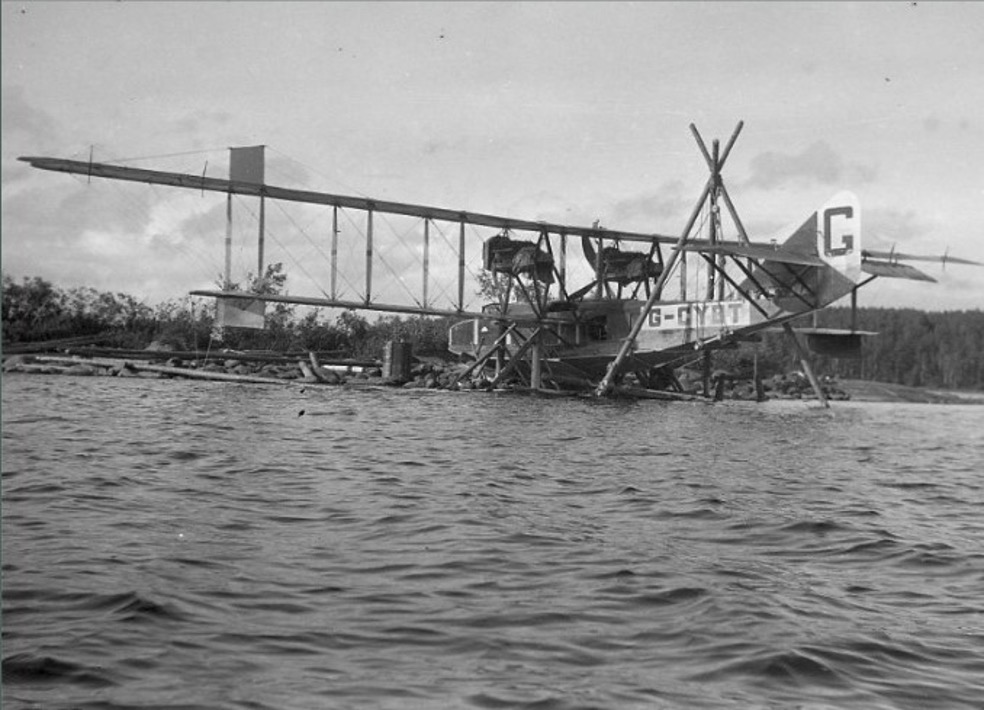

“This photo was taken on July 31, 1922. The G-CYBT made a trip to Kenora and got lost along the way and landed in Pikangikum. There were no maps. Whenever they’d see somebody on the water, pilots would land and ask them to draw a map. Can you imagine flying a big airplane like this and just working off a hastily drawn sketch that has no landmarks? Well, they’d get lost again and they would land again…”

The momentous event of seeing a plane land for the first time is still remembered in the oral histories of Pikangikum residents, said Gerald. “They talk about how afraid they were when this huge gichi zhiishiib, meaning Big Duck, landed. The aircraft was a monstrosity, and it nearly sunk when it struck the only rock near the surface of the lake. They managed to get it to shore, which you see in the photo.”

What are these women looking at?

“These women are all looking to the right,” noted Gerald. “The big question is, what were they looking at?” Gerald solved the mystery by looking at photo archive numbers.

He explained that pilots and surveyors sent photos to different archives, so their photos were numbered differently. “The first photo was taken by a pilot. The number is illegible, but it ends in 1925. The second photo of the women was taken by a surveyor and labeled T.S.10127.”

By putting surveyor photos T.S.10122 and T.S.10127 in sequence, Gerald noted there were only four pictures in between. “It was that same day,” he concluded. “That’s what these women were looking at. They were probably seeing Big Duck, the very first airplane to land in their area.”

Gerald credits a small group of researchers for helping him “figure this out.” He says, “Their guidance has advanced my understanding of all the activity around airplanes, surveying, etc.”

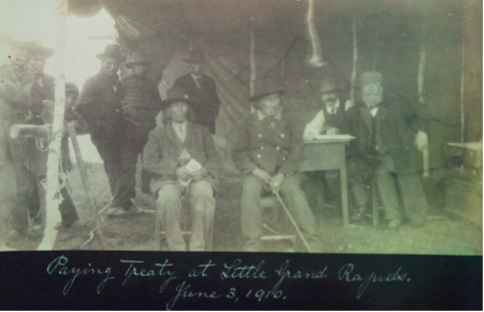

5. A special treaty list reveals who was standing in line together

Gerald presented Treaty Lists and colonial practices that shaped how local Anishinaabe names were documented and changed.

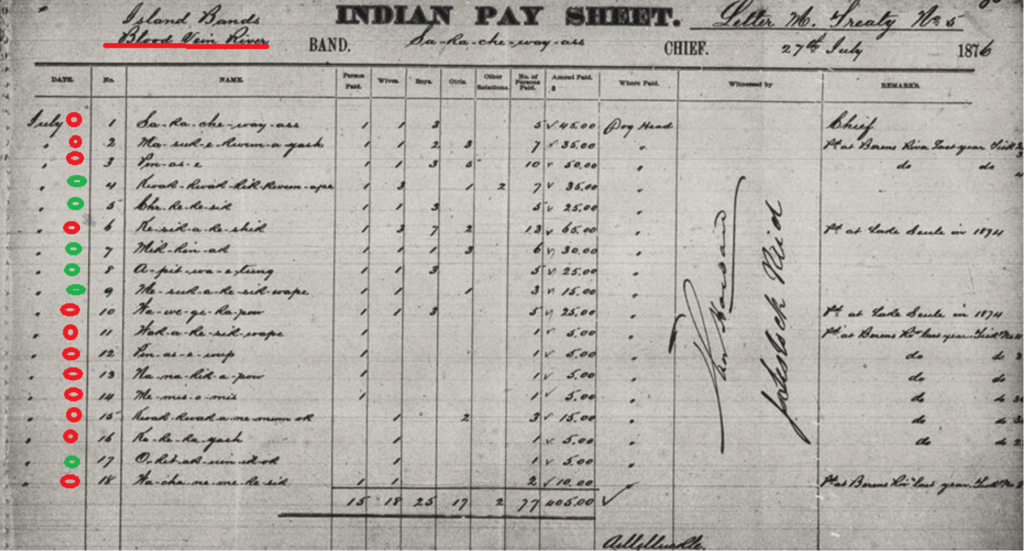

Blood Vein River Treaty List

Here, by 1876, they call it Blood Vein River,” said Gerald, as he pointed to the top left of the pay sheet. “Until around 1820, it was named Blood River, and now it’s Blood Vein River. So something happened in there. I don’t know what it is.”

Gerald turned his attention to the 18 names listed on the sheet. “These are Anishinaabe names. At the top of this list is a prominent name, Sagachiwayas, who was the chief,” said Gerald. “He was also known as Peter Stoney. We know that from a different document.”

Sagachiwayas had also collected treaty in 1875 when Treaty 5 was signed at Berens River, said Gerald. “The names with red dots beside them had collected treaty elsewhere, so they weren’t allowed to negotiate this treaty. Only six people on this list, the ones with green dots, were permitted to negotiate the treaty.”

The other ones had already all collected at either Berens River or at Lac Seul (Lac).

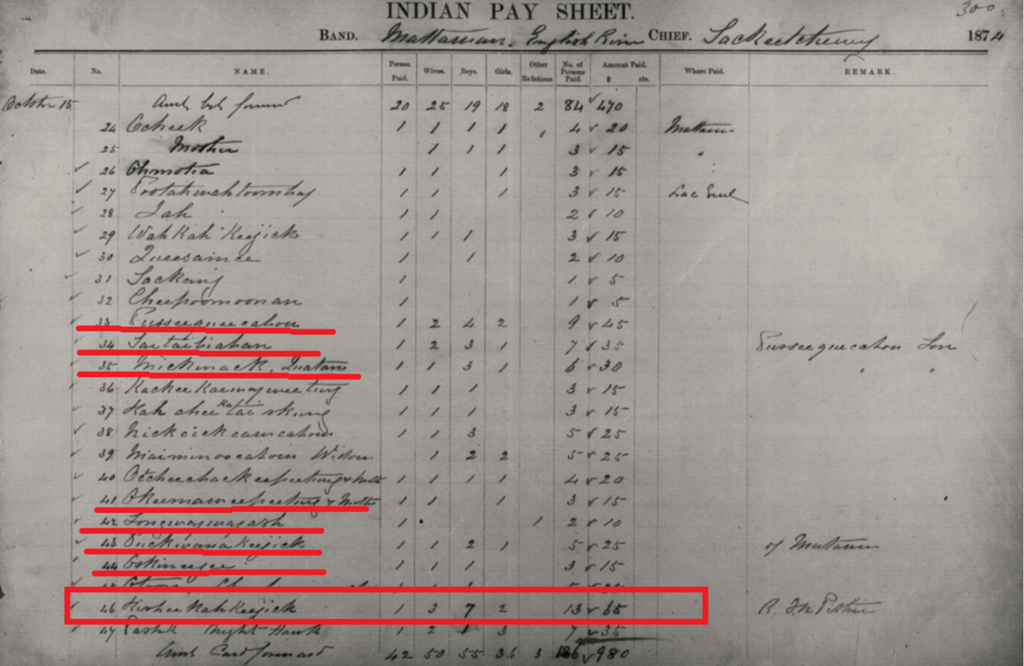

Lac Seul Treaty List

The names on the treaty pay list for Lac Seul in 1874 (below) are familiar, said Gerald.

“These are Upper Berens people for the most part, along with [Kisikakishik (#46 in L.S. list and #6 In B.V. list] who’s from Bloodvein. [Oshkineegee #44 In L.S. and #22 in Sandy Narrows list] is from Little Grand. [Kackeekaiwayweetung #36 In L.S. list and #20 on Sandy Narrows list] is from Pauingassi. And the rest are all from Pikangikum and Poplar Hill.”

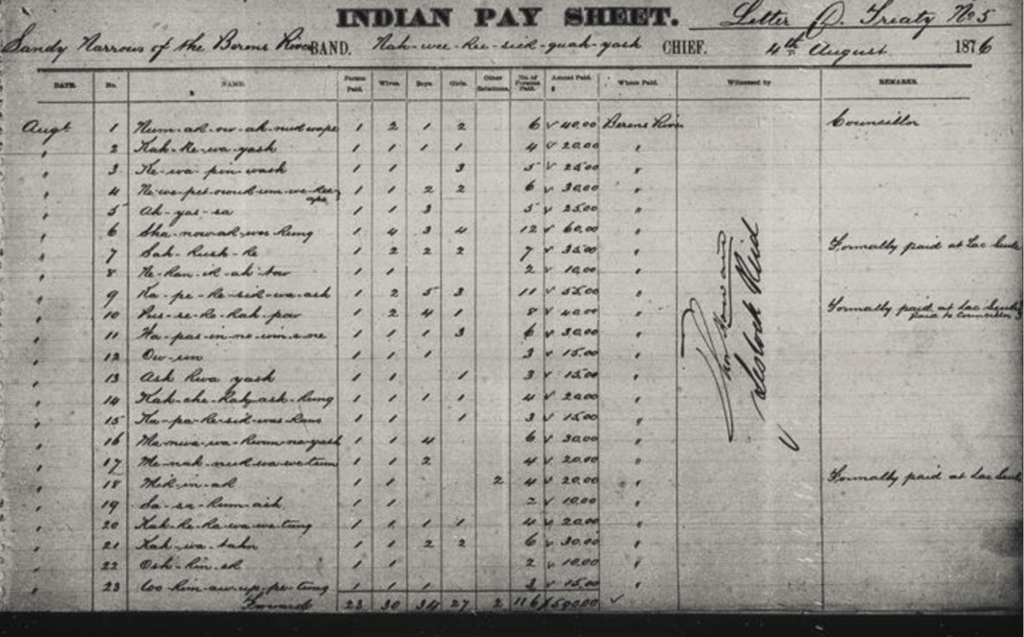

Sandy Narrows of the Berens River Treaty List

Gerald emphasized the importance of the Sandy Narrows of the Berens River list.

“This was the first time these names got recorded formally,” he explained. Gerald said the list is unique in its accuracy. It is based on Anishinaabe clan names.

“What happened here is that people acted as we do today. When you’re with friends or family that you’re close to, these are the people that you cluster up with in line. They were together in line for the treaty money.”

Gerald pointed out the names of people who were standing together. “Ayasa #5 (also known as Naamiwan, or Fairwind fm Pauingassi)was the son of Shenawakoshkank #6. Newepeenoukumwekwape #4 was another one. He is the brother-in-law to Ayaasa #5 and son-in-law to Shenawakoshkank #6. They’re all very close together. When you get down further, these are all the Pikangikum and Poplar Hill people. So that’s how they clustered up. And that’s just human nature.”

But the traditional Anishinaabe system of lining up based on the strength of kinship ties was soon lost.

“The British were a very regimented people,” noted Gerald. “They were very orderly. They liked things done in a certain way. After that year, people were lined up alphabetically according to the sound of their last name. And after 1891, they were lined up alphabetically according to the English, Scottish, and French names imposed on them.”

The impact of this erasure (loss of the knowledge of clans) continues to affect families, communities, and their connection to the land.

“People have forgotten their history. They’ve forgotten their relationships because it all changed from the traditional Anishinaabe names in the clan system.”

With traditional names having “disappeared off the map,” Gerald now uses “forensic strategies” to track the lineage of community members in Pimachiowin Aki.

His message is clear: remembering the past is crucial to understanding the present, and preserving ancestral connections is vital for future generations.