By Doug Gilmore

Recently I found myself reflecting on the early days of Pimachiowin Aki. Many fond memories quickly floated to the surface. At the time my role was Park Superintendent of Woodland Caribou Provincial Park, located in Northwest Ontario near the town of Red Lake. Woodland Caribou Park is part of the Pimachiowin Aki World Heritage Site. I recall that I was very excited to take part in the Pimachiowin Aki World Heritage Site process, although at the outset the site had yet to receive that wonderfully appropriate name.

It was in my role as park superintendent only a few years earlier that I had initiated and led a planning process for Woodland Caribou Park. That project was one of my first exposures to working closely with First Nation Communities. To expand on the previous sentence, I must add that this exposure cemented my understanding and belief that working together with Indigenous people is extremely beneficial. Looking back, coming from my Wemtigoshi background, I can easily admit at the outset to looking at things from one perspective, but keeping an open mind to all possibilities. It took no time at all to come to the realization that this was the only way forward and that any product which may result from our efforts would be the better for our working closely together.

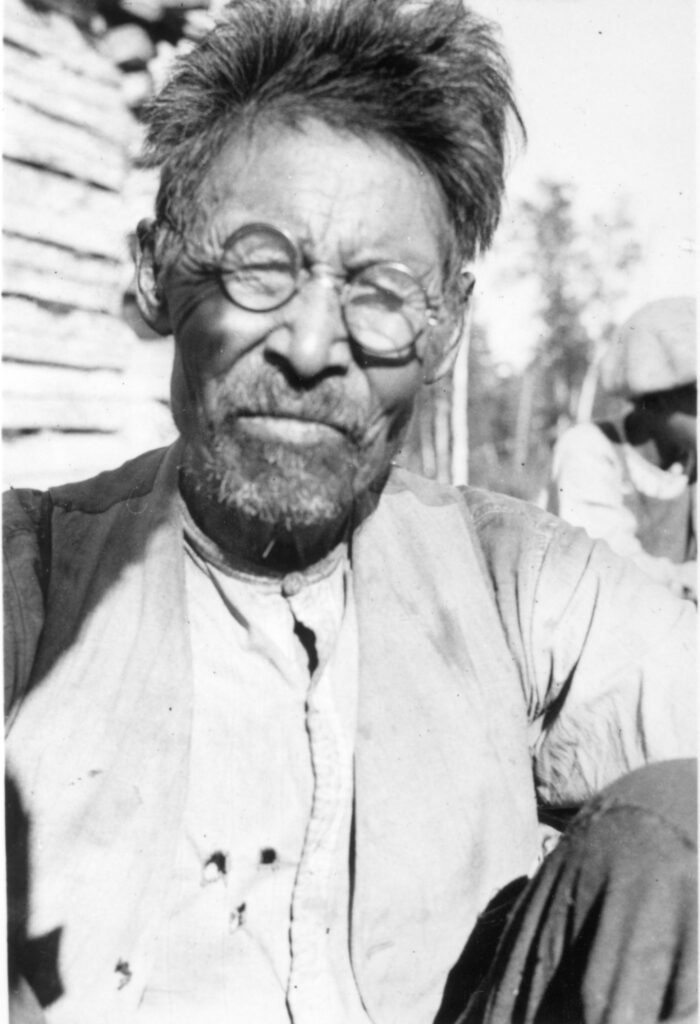

At an early Pimachiowin Aki meeting, members from each community expressed very clearly what was important for their community. Things like protecting the rock paintings, not to over harvest the animals, acting carefully around areas that act as water filters for the watershed were comments common to most. People spoke about the high levels of unemployment in their communities and the desire that this project could help to alleviate that. It was clearly stated that their traditional lands used to provide a livelihood for their people but this no longer was the case. Community presentations included the desire from their Elders to “protect traditional lands”. One individual recalled a comment from a grandparent that “we need to protect our lands” and it came with a warning that “there may be difficulties ahead”. Another spoke about how he was raised by his grandparents. They taught him how to preserve food in the summertime and spoke about how they used the land and how he wanted to keep the teachings of his grandfather. He gave an example where people used dried moss as diapers and that one of the teachings of the moss was to put it back in its place.

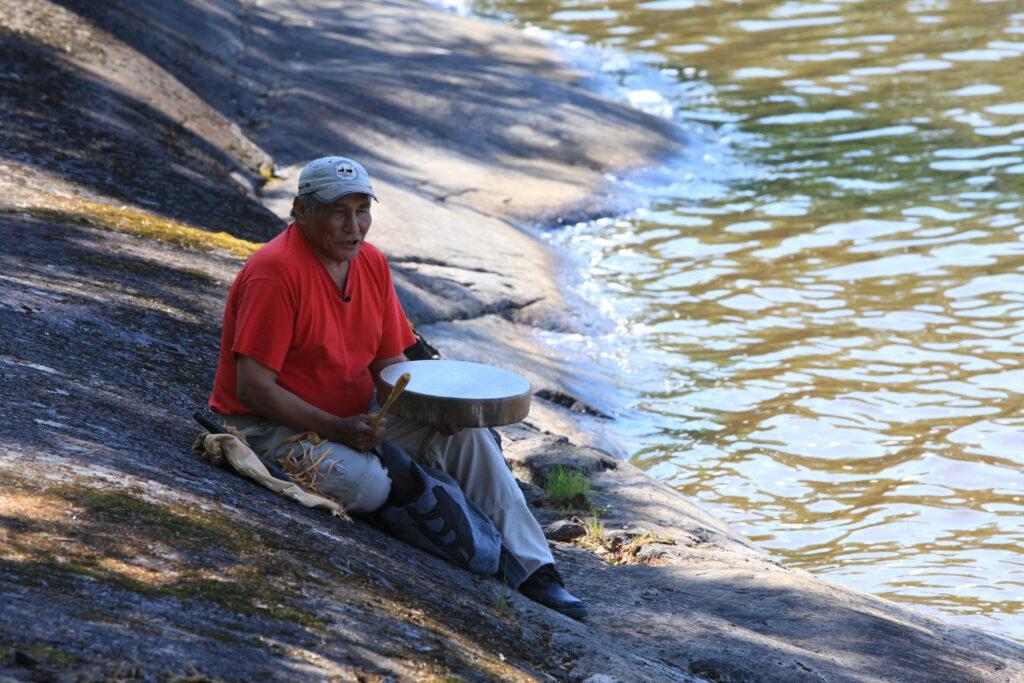

Someone much smarter than I at an early meeting summarized all the comments by describing the activities of the people on the land as the cultural foundation of the project. The term Living Landscape was used, reflecting on the strong linkage between the land and the people. Strong linkage? I have come to understand it as an inseparable linkage.

Fascinating… an education in real time.

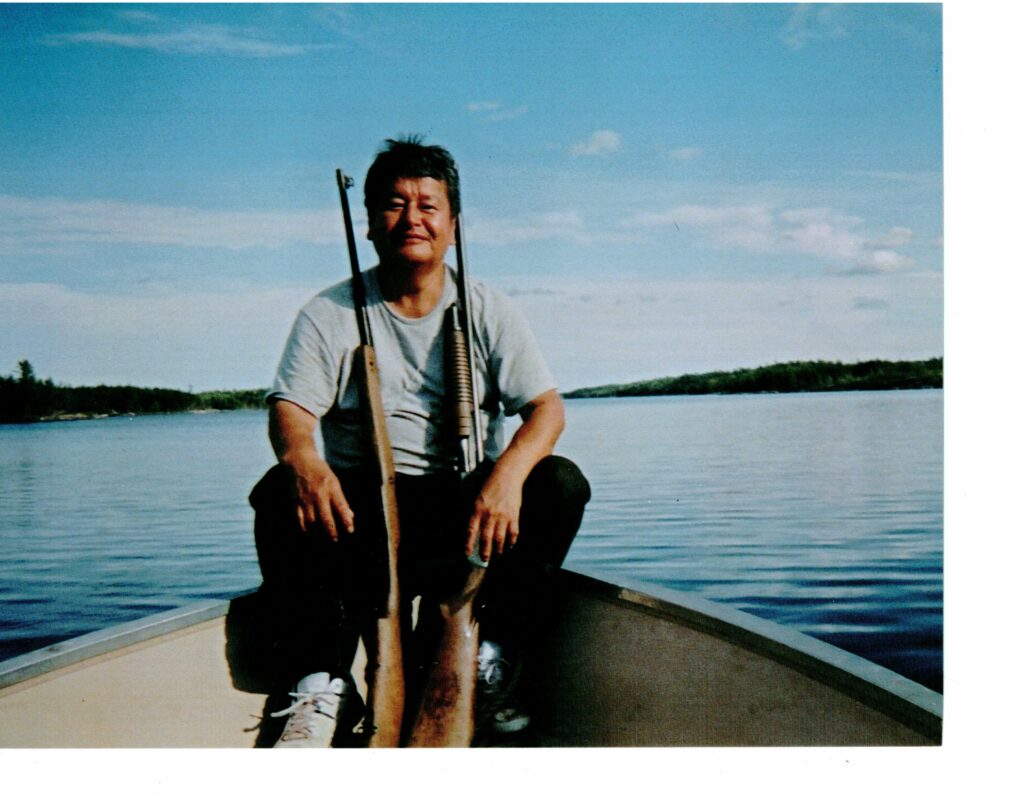

In the months and years to come the World Heritage process continued to be an educational one, enlightening me on what it meant to grow up in a remote First Nation Community where at one time it was normal or part of everyday life to go out on the land or trapline to perform livelihood pursuits. This once normal activity would slowly or in some cases abruptly change to where it became more and more difficult to access the bush to carry out livelihood activities on a regular basis.

The World Heritage process also included working as a member of parallel planning processes with Little Grand Rapids and Pauingasssi First Nations for the part of their traditional territories that lies in the Province of Ontario. This included many opportunities to visit these communities, meet with elders and community members in workshop and open house events. It also included travelling to Weaver Lake as a guest of Poplar River First Nation to attend a Pimachiowin Aki meeting and workshop there.

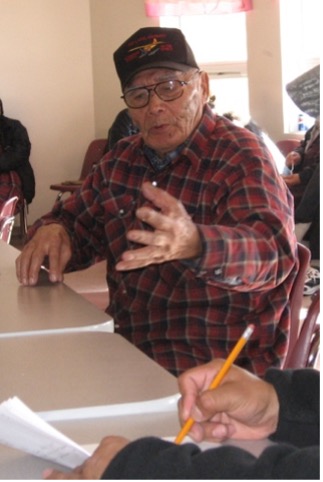

The workshop events were perhaps the ones that were most impactful for me as we were able to spend a few days in the communities allowing for a less frenetic pace for the exchange of information. Remaining with me are memories of sitting with the late Russell Keeper pouring over maps of his trapline and of him describing in detail the landscape of his youth and how it supported his present-day activities on the land. What also sticks with me is the pride in the voices of various community members as they relayed stories and teachings of their family members and how they are determined to bring them forward and keep them going. Equally impactful was the coordination and care shown by the land use planning representatives for each community, Augustine Keeper and the late Joe Owen, and on the performance of their duties and the responsibility that the community had entrusted them with.

It was brought to my attention that although I was working in partnership toward our common goal, I was sometimes guilty of describing Indigenous land activities as happening in the past, not in the present. Not intentional of course but my background being what it was I periodically fell into the trap of just copying what I heard or read. There is a term for this, a term identified to me by an Indigenous planning partner as “the Invisible Indian Syndrome”. It’s a real thing, definitely! What an eye opener. You’re never too old to learn.

The take away from my perspective is this, the Indigenous people of Pimachiowin Aki gain their life from the land, they always have. Their links to the land are real and permanent and it is through Pimachiowin Aki that they will share it with the world. The stories, traditions and culture they choose to share with the world will be the foundation for the site into the future. For me I think this is unique, for them it’s probably everyday life.