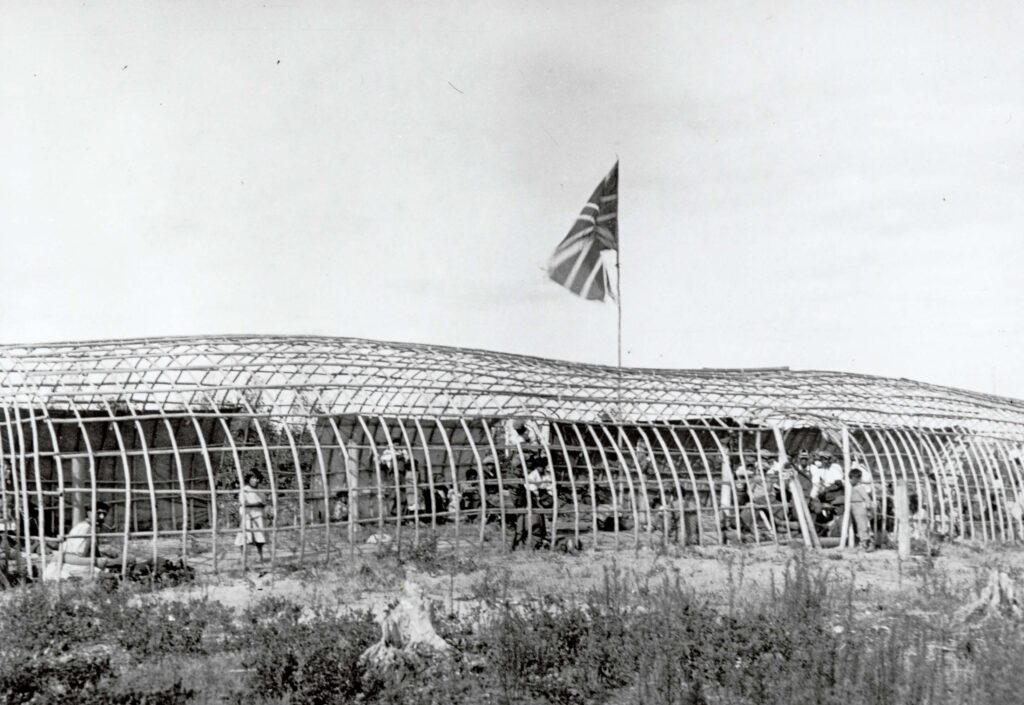

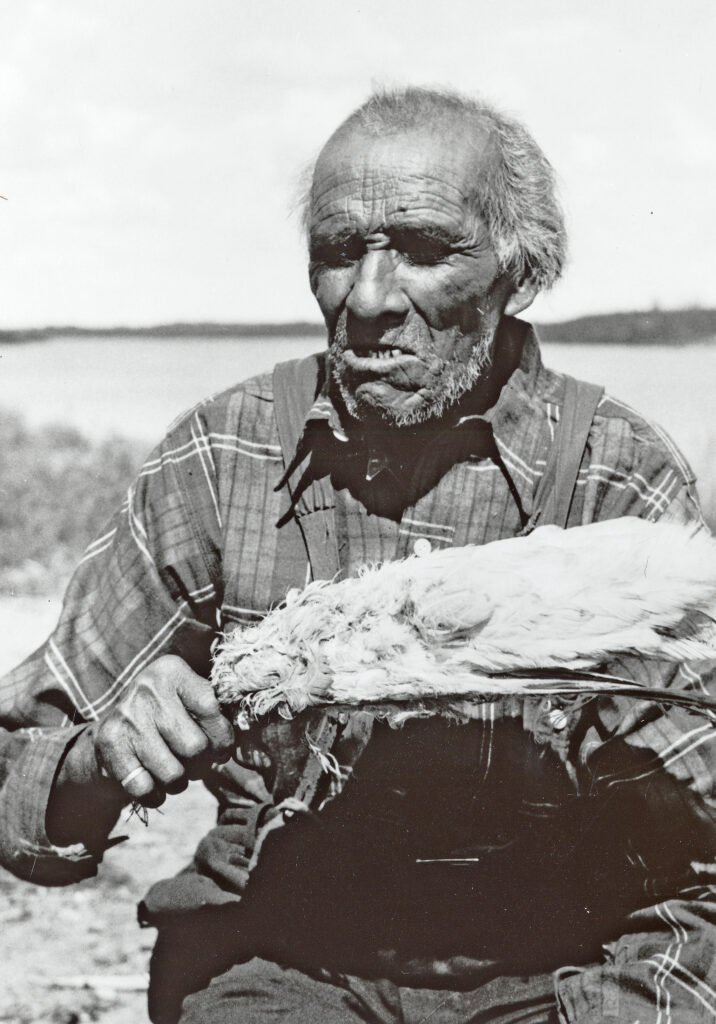

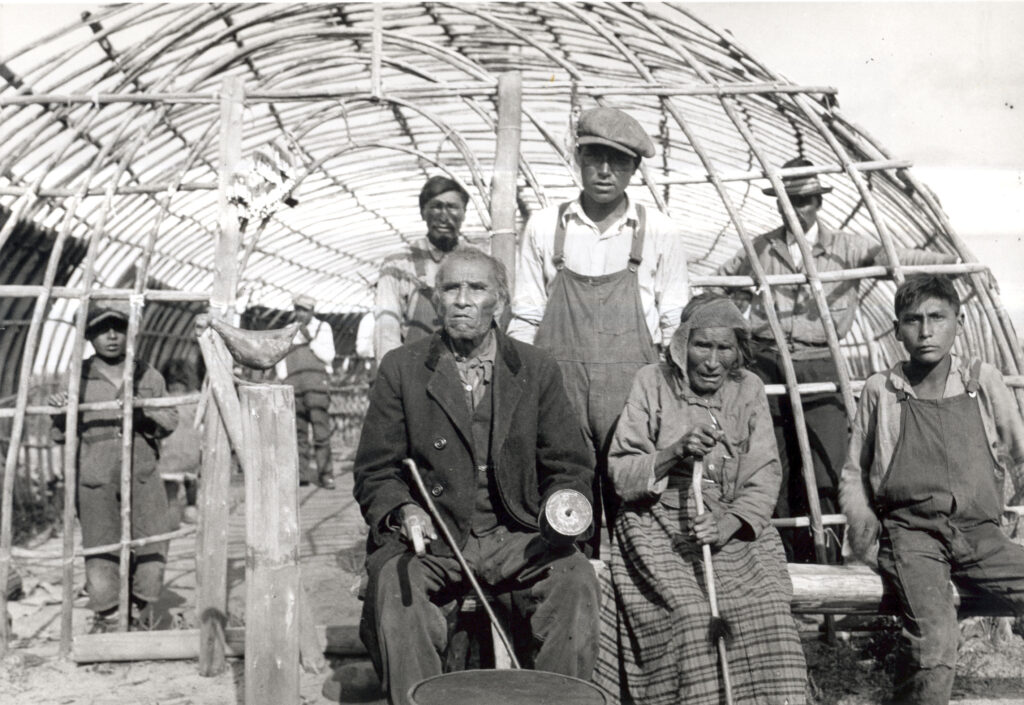

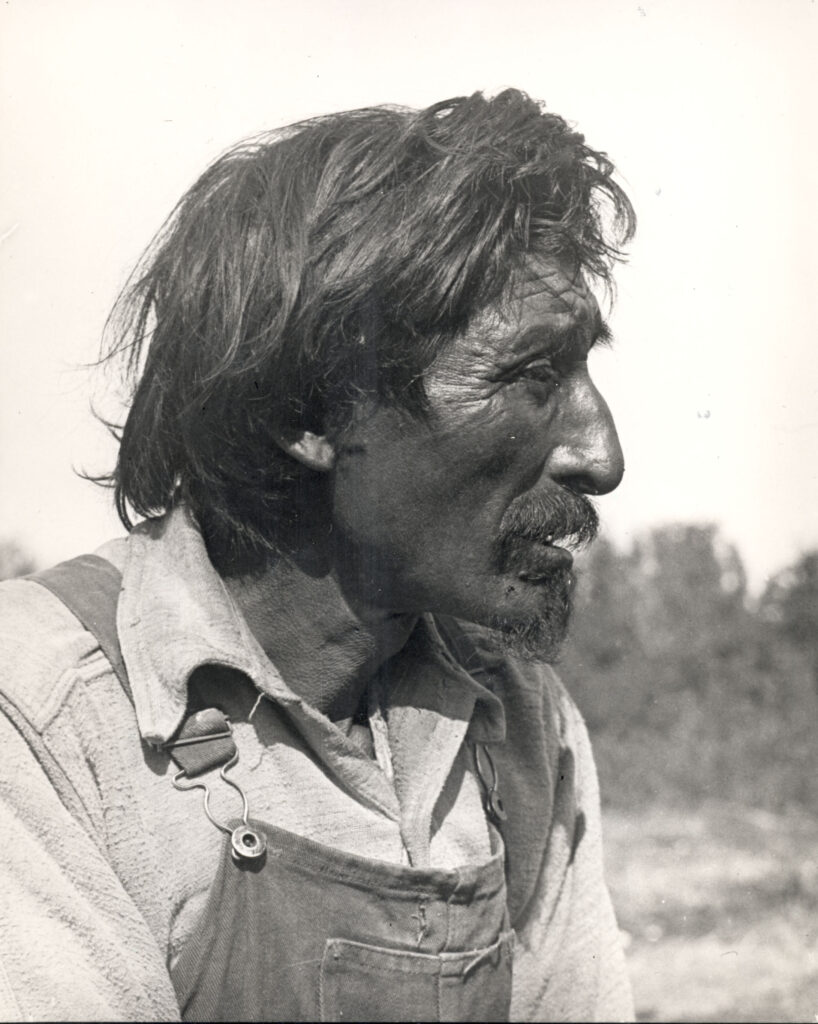

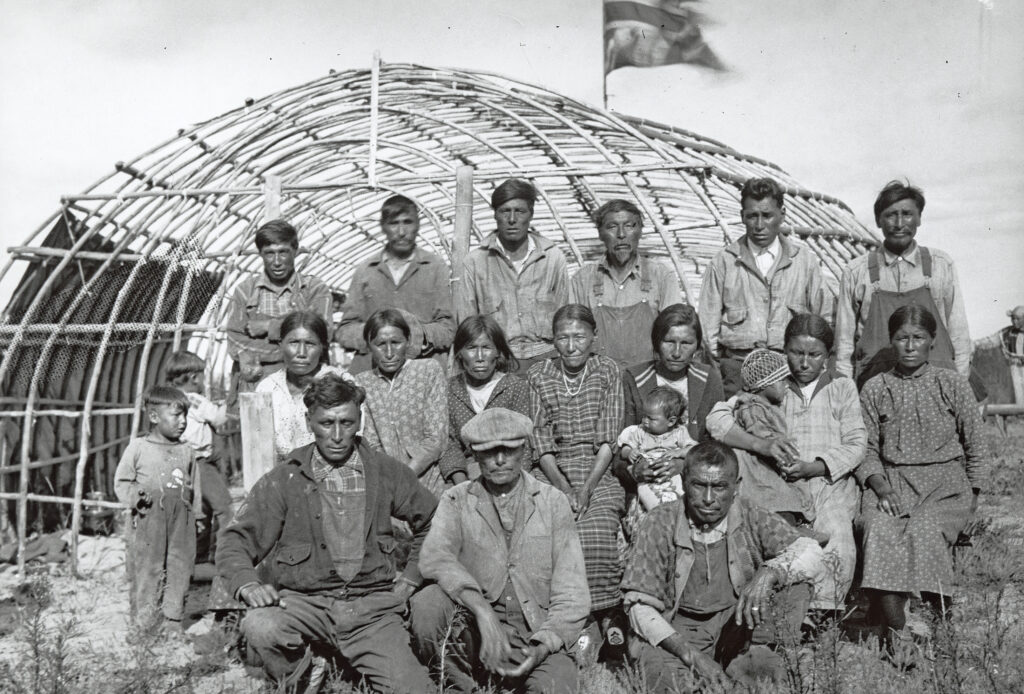

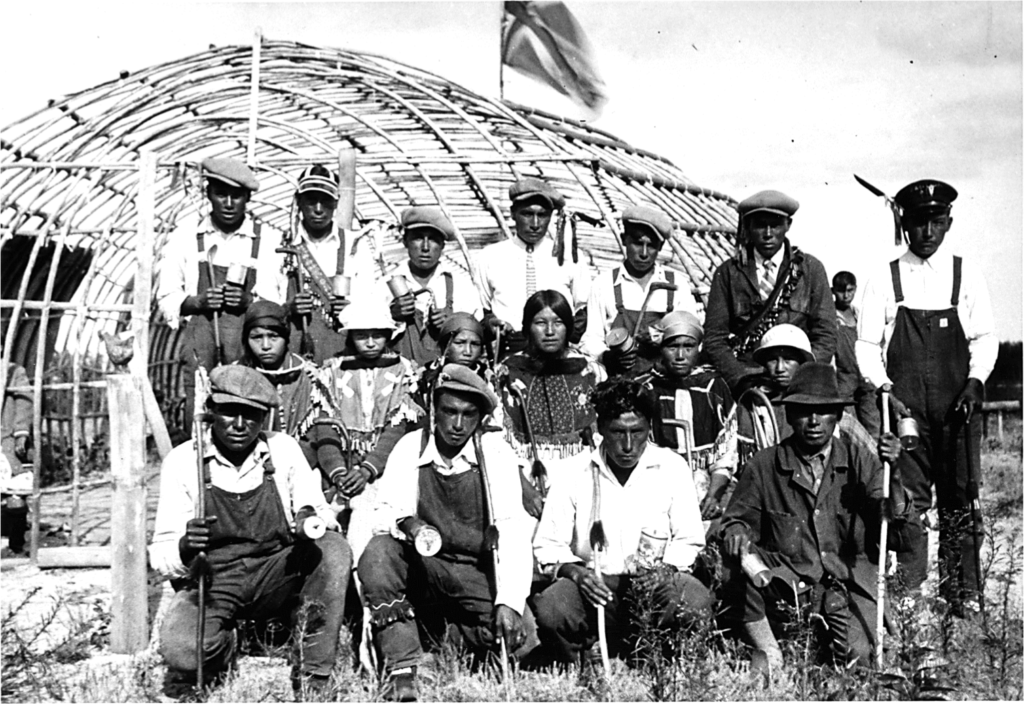

The ceremonial objects in the Pauingassi collection were photographed in use in 1932 by American anthropologist A. Irving Hallowell. In 1970, they were gathered up by another anthropologist, Dr. Jack Steinbring of the University of Winnipeg, who placed them in the University’s Anthropology Lab and promised to keep them safe.

When it was discovered that artefacts were missing from Pauingassi, my husband, (the late) Nelson Owen spoke with his grandfather (the late) Omishoosh on a number of occasions and felt there was a great need to protect and recover what had been taken. We contacted the newspaper that ran the article about the disappearance of the artefacts and they put us in touch with Dr. Jennifer Brown and Dr. Maureen Matthews. Then we began our quest to retrieve the artefacts and get them under community control.

Nelson consulted with the heads of all 25 families in Pauingassi and with their agreement, requested that the collection be repatriated to the community with our family as guardians, not owners. It took many years to complete the repatriation after our initial request in 1998. The collection is now cared for at Manitoba Museum and we are confident that the artefacts are in a safe place, although a number are still missing. On this journey of recovery, we have taken up the mantle of guardians so that our children and all children of Pauingassi will have a chance to learn from these storied objects and understand the role they played as Omishoosh wished.

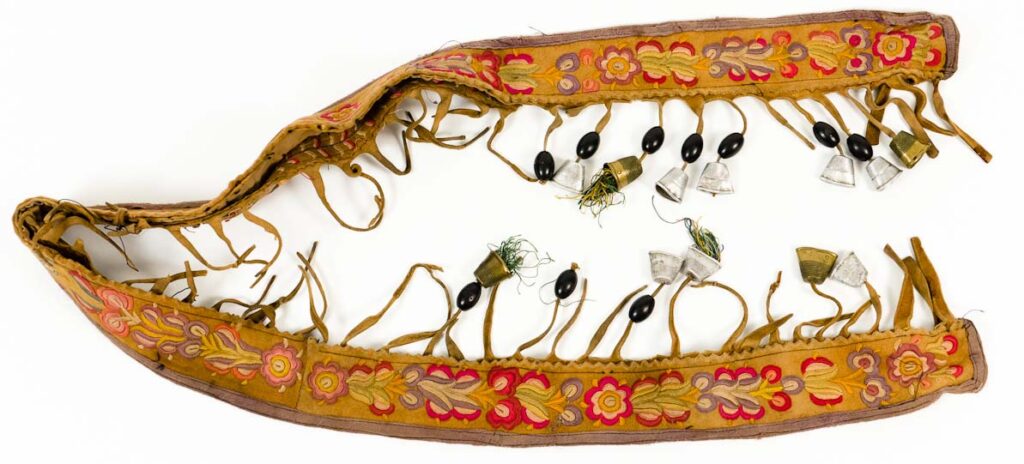

The artefacts range in age from 50-200 years old. They are unique and unusual in design and reveal important ideas about Anishinaabe culture. If I were to show the collection to someone and point out the two pieces that speak to me, it would be Omishoosh’s embroidered apishtaagan (chest protector) and the wawezhi’on (dance cape) that belonged to Koowin.

Learn more in Obaawingaashing Gichi-Aabijitaawinan | Pauingassi Collection, a book about the Anishinaabe ceremonial artefacts and community collections. You can donate to Pimachiowin Aki World Heritage Fund to receive a copy. Visit the Shop page for details.

Dr. Matthews, Joshua, and I are planning to develop an exhibit with the existing artefacts as well as search for and bring home to the collection any pieces that were moved from Manitoba.

The most significant pieces I would say are the drums. They carry a great deal of knowledge and are highly respected for their role in the ceremonies of the people of Pauingassi First Nation. Fortunately, we have pictures of the owners, stories about their use, and the artefacts themselves, which is rare.

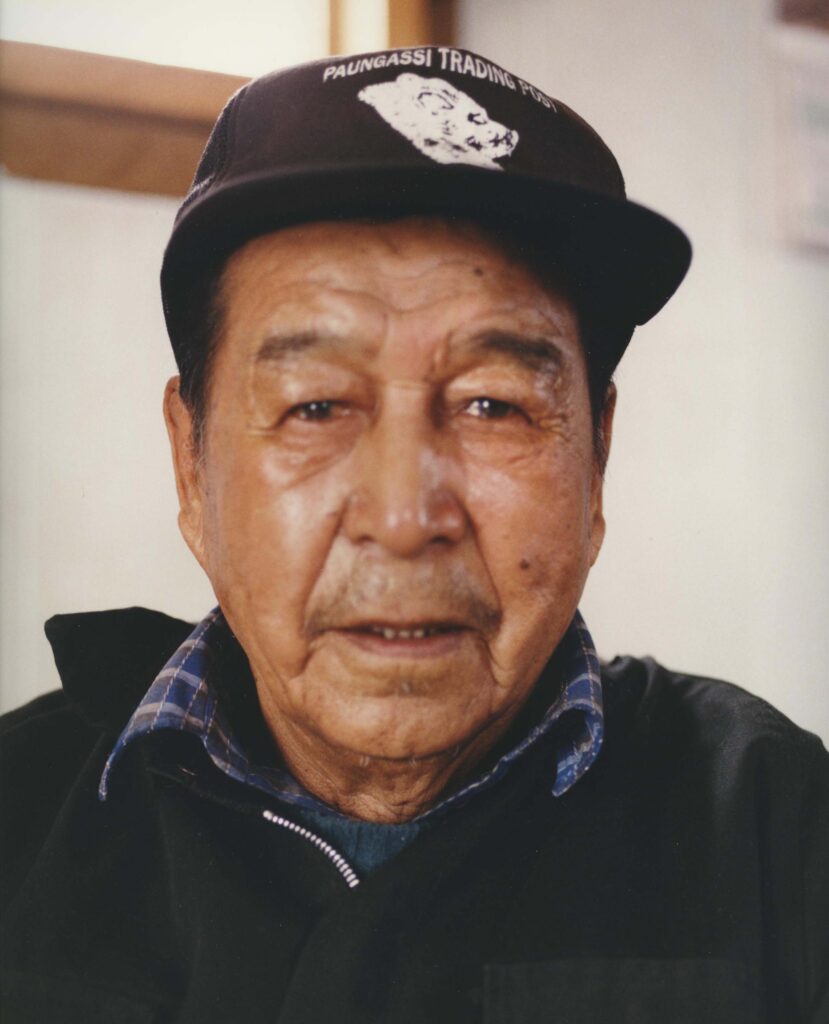

—Elaine and Joshua Owen, Guardians

Shop

Shop