Keeping the Land

Cultural Heritage

pP WLUnWnB

Cultural heritage expresses who we are and how we live. It consists of everything that we value and share through generations:

- Objects that we can see and touch, like cabins, travel routes, manoomin (wild rice), landscapes and artifacts

- Intangible things like language, songs, knowledge, beliefs, and practices

We are always singing. We have songs for healing, songs to the Creator, songs for ceremonies, songs for dancing and having fun, songs for the sunrise, songs to honour people, to give thanks, and many more. Songs are given to us from our Elders or come to us in dreams. We can’t just sing songs we hear; they need to be given to us.

Elder Abel Bruce

Why Cultural Heritage Matters

Cultural heritage is invaluable. It connects people and unites communities, helping us understand who we are and how we contribute to the world. Cultural heritage provides us with our livelihood and links us to land-based knowledge and skills that have empowered Anishinaabeg to protect and preserve Pimachiowin Aki for millennia.

How We Protect Cultural Heritage

Taking Inventory of Cultural Sites

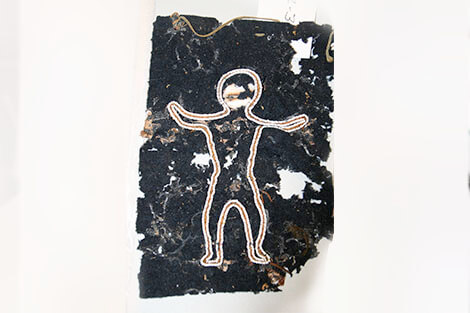

We are crossing land and water to inventory Pimachiowin Aki’s vast array of cultural sites, including petroforms, pictographs, Thunderbird nests, cabins, campsites, and ceremonial sites.

Some of our earliest research began with memory mapping. Anishinaabe Elders walked the land with us and showed us places and things that are only known because they have been passed down from generation to generation through oral stories. With Elders’ guidance, we created maps of cultural sites along travel routes on land and water. In some cases we returned with archaeologists and discovered ancient Indigenous artifacts, including pottery and art, dating back thousands of years.

Registration = Protection

Pimachiowin Aki’s cultural sites are being registered in government databases to identify and protect these sites. For example, if someone applies for a permit to cut trees in a way that would disturb a Thunderbird nest, the permit could be denied.

Preserving Pictographs

Pictographs are recorded in 30 locations across Pimachiowin Aki. Because we know where the pictographs are, our Guardians can monitor these cultural sites to make sure people aren’t compromising their integrity.

Preserving Anishinaabe Language

Culture and language have evolved together and are inseparable. Keeping the Land means preserving the language — only Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe language) can express the stewardship laws and give meaning to cultural sites. Anishinaabemowin reflects how:

- Natural and dream worlds are perceived

- Places are known and named

- Animals and plants are understood

- Hunting and other practices are expressed

We conduct research and language retention surveys to ensure that Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe language) continues. We support land-based learning in Anishinaabemowin, and celebrate the songs, stories and teachings that form the unique cultural link between the people and the land.

Documenting Named Places

Most people think about a landscape as a physical and natural backdrop for life, a sort of stage upon which life happens. But in the Ojibwe way of thinking, the landscape is alive. It is full of human and non-human beings that engage with the people who know a certain place thoroughly.

Pauingassi Lands Management Plan

We are researching and documenting named places to help preserve Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe language), and the traditional knowledge that is passed down through generations through teachings, stories and songs.

On Google Maps

We forward the named places to the provincial government so that they are included in official databases and topographic maps and will show up on popular sources like Google Maps.

Keeping Tradition Alive

The First Nations of Pimachiowin Aki are creating maps of named places for their schools and community spaces. The maps give meaning to these places and help keep the language and stories about these places alive.

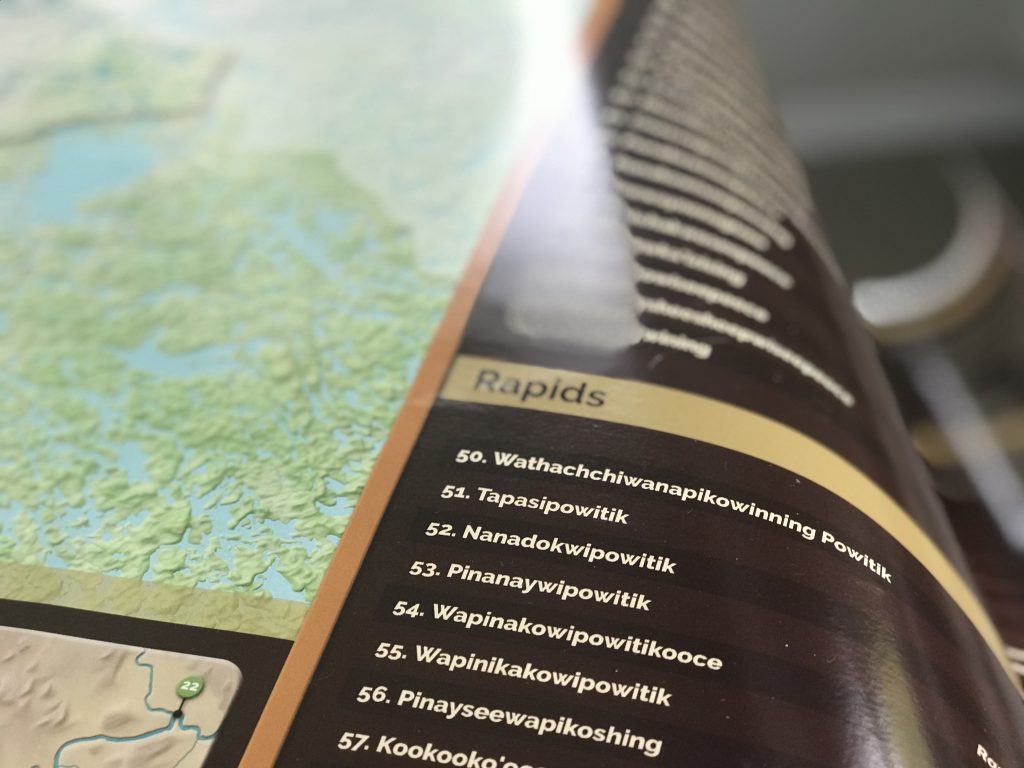

Poplar River First Nation—149 Named Places

The Poplar River First Nation Traditional Place Names map includes 149 named places, including rivers, lakes, creeks, rapids, points, islands and other named places like Wapiskapik (the rock island that was painted white so it could be seen). The place names on the map are officially recognized in provincial and national geographical names databases.

The map was delivered to the Elders who shared their knowledge over several years to help document the personal and collective histories of the people who have travelled through, observed and lived on Poplar River First Nation ancestral land, Asatiwisipe Aki.

Bloodvein River First Nation Place Names Map

Bloodvein River First Nation has completed a Traditional Place Names map, preserving Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe language), history, navigational information, teachings, beliefs and practices important to the First Nation and Pimachiowin Aki World Heritage Site as a whole. Facilitated by Bloodvein River Guardian Melba Green and Pimachiowin Aki Director William Young, the map was created by Elders and others who shared their knowledge over several years. The map is currently under review and may not be considered final. Miigwech to everyone involved for deepening our understanding of places and our connections to them. The final map will be displayed in community spaces and the new school when construction is completed.

Download the Bloodvein River First Nation Traditional Place Names Map

Connecting Youth to Cultural Heritage

We link youth from Pimachiowin Aki to their cultural heritage by organizing visits to the Manitoba Museum in Winnipeg. The museum houses artifacts from Pauingassi and provides exciting opportunities for language teaching though the Spirit Lines Project.

Want to learn more about how to protect cultural heritage?

Follow us on social media:

Donate

Donate